In Stanley Donwood’s There Will Be No Quiet, the artist behind Radiohead’s iconic artwork reveals the creative process that has earned him a cult reputation. Dan Richards reviews.

“It is not at all easy to become an artist and it’s not something I’d advise, even though from a distance it looks like a fairly relaxed course of action…Everything is difficult to start with, gets harder, becomes impossible and then it ends up OK.”

I’ve known Stanley Donwood — he of several names, myriad approaches, multifarious media; the man who does the Radiohead artwork — for getting on 13 years. I first met him at the simultaneous launch and closure of his record label, SIX INCH RECORDS, in a London bar — the sort of gaff where, when the bill arrives, people either pay without looking or start screaming and bleeding from the eyes. Stanley had just bought a round of drinks for his roster of musicians and was stifling hysterics having gone bankrupt. I introduced myself. Could we have a chat?

At the time I was trying to write a book about artistic space and process but I’d never really written a book before and wasn’t sure what I was doing. Stanley and I lived in the same city as it turned out. He had a cronky old studio, the sort Tom Waits might sing about, which was very cold. There, we spoke at length, over several years and a lot of wine, about art or, as he put it “the stuff I’m doing and the stuff I’ve done.” Nobody, he assured me, nobody really knew what they were doing; I should keep going with my book and see what happened.

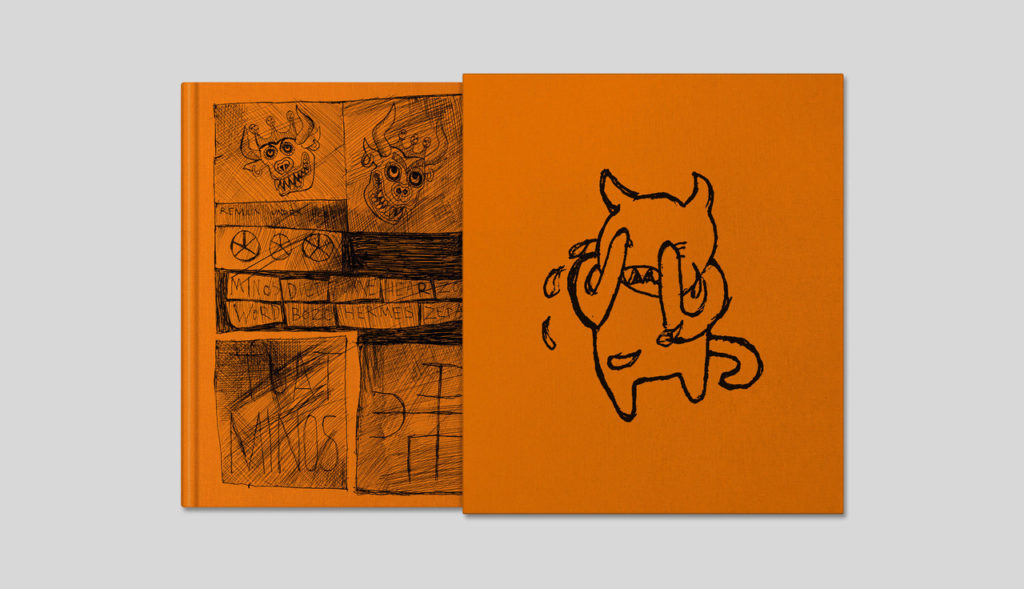

Now, Stanley’s got book out named There Will Be No Quiet which collects all his ‘stuff’ together and recounts, as best he can recall, what happened. Looking back at the album covers, linocuts, print works, paintings, short story collections, op-art cupolas: his oeuvre, I suppose — much of it boshed-out in the time I’ve known him — I think cold studios are one of the few consistent elements of his work: cold studios and those scary bears with the big eyes and pointy teeth…

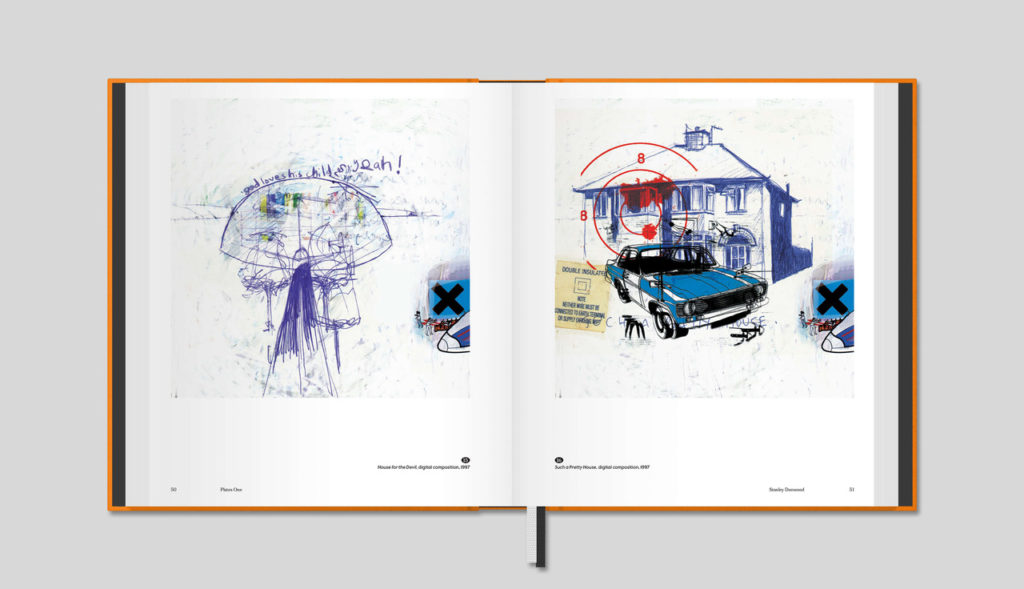

A swimming pool of blood, maps, mazes, meteors, food dye strata. A-bombs, X-rays, symmetrical suburbia, Serbia. Dark forests. “Things went fucking terribly.” Pan, Piranesi, Minotaurs, melancholia, manholes, man-traps, graffiti, phlegm. Yggdrasil, pebble-dash, Centre Point, Rendlesham. Magazine, Anthropocene, Brassaï, Ballard, Bad Island. Twombly, tax-havens, ravens, wax. Kid A, crosshatch, Sleaford Mods. “I have failed in art more often than I’ve succeeded, and most often nothing has gone as planned.” Wages (in packets), paste (in buckets), barns (in Oxford), diskbox (In Rainbows). Smeuses, Eraser, Falluja, Araldite.“I used to love faxing.”Slipcase, Soken Fen, fingerpost, bastards. FRAUGHT WITH DIFFICULTY // A SECRETIVE CABAL // THE LUNATIC FRINGES OF THE RURAL POPULATION // PREHISTORIC SCREECHING // DELIBERATELY MAKE LIFE DIFFICULT. Nether, weather, Heidelberg, Rauschenberg, iceberg. Lamping, Pilton, Porton, Parton. Exeter, airlocks, Over Normal. “We sat round the table and looked at the possible titles all printed out and that one looked the best so that’s what it’s called.” Toxic, box-set, Brexit, arsenic, Eylot, OK, Fleet Street, Troy. Turpentine, ketamine, letterpress, Hell. Dieback (ash), Debenhams (for), DEMONS (against), green chapels (Orford Ness).

Many times during our conversations he talked about his horror of repeating himself. The next thing always the best and most exciting thing — the chance to begin again, afresh. He sees himself as a commercial artist, he said. In another life he’d be painting pub signs and narrowboats but, as it is, he’s the visual conduit for Radiohead’s music — always reacting and responding anew. The idea is to create artwork so different and diffuse that the man in the street might think it’s by a different person every time. The dream is to be anonymous and lost in the work. But now he’s written a book with him name on the front all big. He really should have thought that through.

And he sometimes works with Thom Yorke and they ping-pong ideas back and forth, adding a bit, deleting a bit, overwriting, overbic-ing — “faxes were really good for that” — and generally fighting until it’s good; or, failing that, ‘different’. Yorke has written a warm, funny stream-of-consciousness introduction to There Will Be No Quiet about their shared ‘myopic vision’ —

“First day of college. Donwood in a tweed cap and green tweed suit. Decided I didn’t trust him. Had a feeling I’d end up working with him. Him reading a book. Looked like he was there by mistake. … Two years later persuade the record company that me and my mate from art college are going to do the record sleeve, that we ‘knew what we were doing’. Fully qualified.Found ourselves in the basement of the John Radcliffe Hospital looking for an iron lung…”

“Stanley found the internet. There was a big phone modem. We scanned pictures endlessly, while overdubs happened, painting and erasing with a tablet, layers and layers.”

“Walked the cliffs of Cornwall with flask of tea, sandwiches and sketchbook. Landscape brought me back into myself, using a pen to tell my story through what I saw. Stanley was filling his books with similar things, monster bears for his kids. The pages of our notebooks filled up with the terror of what happened next. Whatever that was.”

“Sometimes I say very little, do very little. Watch him paint. Sometimes I spill turps on a table and watch things destroyed. The fool in the play, the advisor, the ‘not this, ‘what about this?’ Talk about the words. Or I walk in, change weeks’ worth of his work, walk out while he quietly rolls a cigarette.”

23 years of exchanges like that. Or not. Some things happen alone with a chisel.

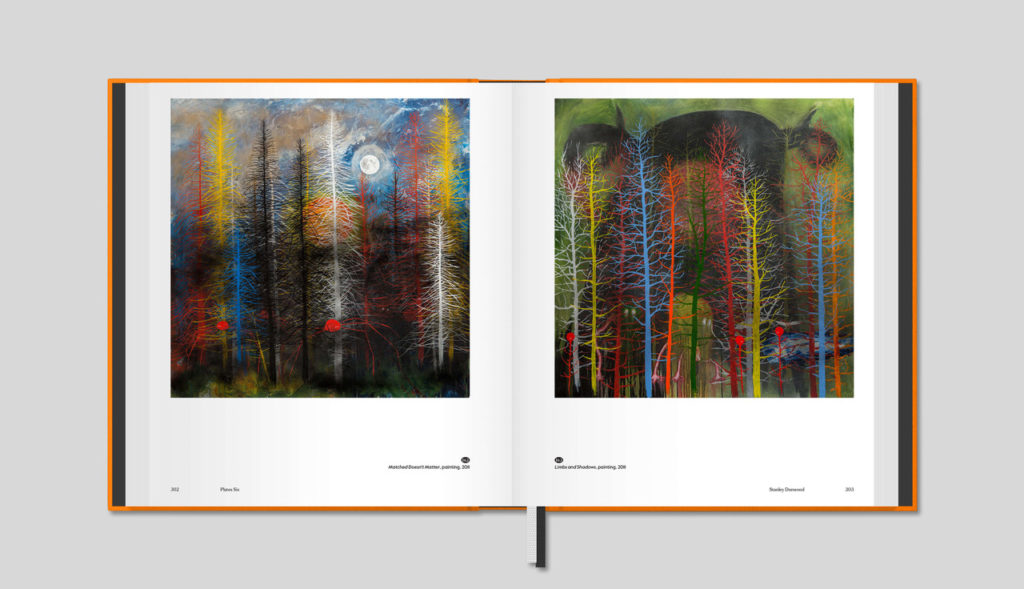

The obsessively gouged apocalypse of The Eraser — black waters and tendril fires engulfing London, wrapping Yorke’s first solo LP — and its sister record, AMOK by Atoms For Peace — a Vorticist vision of LA beset by flash floods and meteors, hewn over years — tell of Stanley’s amazing symbiotic relationships with both Yorke’s music and the printer Richard Lawrence, something Stanley relates with great love and respect in There Will Be No Quiet. Then there are the vibrant fluid, branching capillaries of Radiohead’s King of Limbs. Forests and spirits, fogs and benevolent (?) monsters painted in oils — organic, mysterious, magnetic. I remember him working on those big canvases, spattered and swirling — images akin of the Holloway book we made together with Robert Macfarlane — a slim volume which dealt with ghosts, friendship, deep lanes and landscape; a beautiful pen and ink gyre of tree tunnels haunted by horned spectres which now has its black ballistic Doppelgänger in Ness.

The heavy waters of A Moon Shaped Pool showed another change of direction — metallic liquid marblings, collage and cloud-form abstractions; viscous and erratic — harking back to the nebulous explosions of In Rainbows but new, unique and vital. Another tangent, another approach; the method changing with each collaboration, album, story — and There Will Be No Quiet is chock-full of stories.

A unique chronicle, then, as well as a beast of a book; part The Crying of Lot 49, part Fitzcarraldo; How I Escaped My Certain Fate but with more pens and less crisps. A reckoning of a life spent dreaming and daubing, sketching and painting, listening, connecting, fashioning to suit, devising in-light-of; the most amazing archive of madness and brilliance. A fitting opus to celebrate this most remarkable ‘career’ — although I know he’d hate that word.

And I haven’t even touched on Glastonbury, or the Ballard paperbacks, or that film The Bomb… and I bet he’s working on more stuff even as I write this, the ‘restless and prolific’ scamp.

“When I was a kid, I made all these vows” Stanley said recently. “When I’m a grown-up, I’m not going to learn to drive, which I haven’t done. I also vowed I wouldn’t have a mortgage, which I have done. I also vowed I wouldn’t have double glazing, which I have done … so I’ve basically compromised my childhood ideals on many, many levels. But I’m still making pictures and writing stories, so.”

Lucky us.

*

‘There Will Be No Quiet‘ is out now and available here, priced £28.

‘Bad Island’, an apocalyptic lino-cut parable, ‘a silent species-history in eighty frames’ (Robert Macfarlane) is published by Penguin on February 13th.