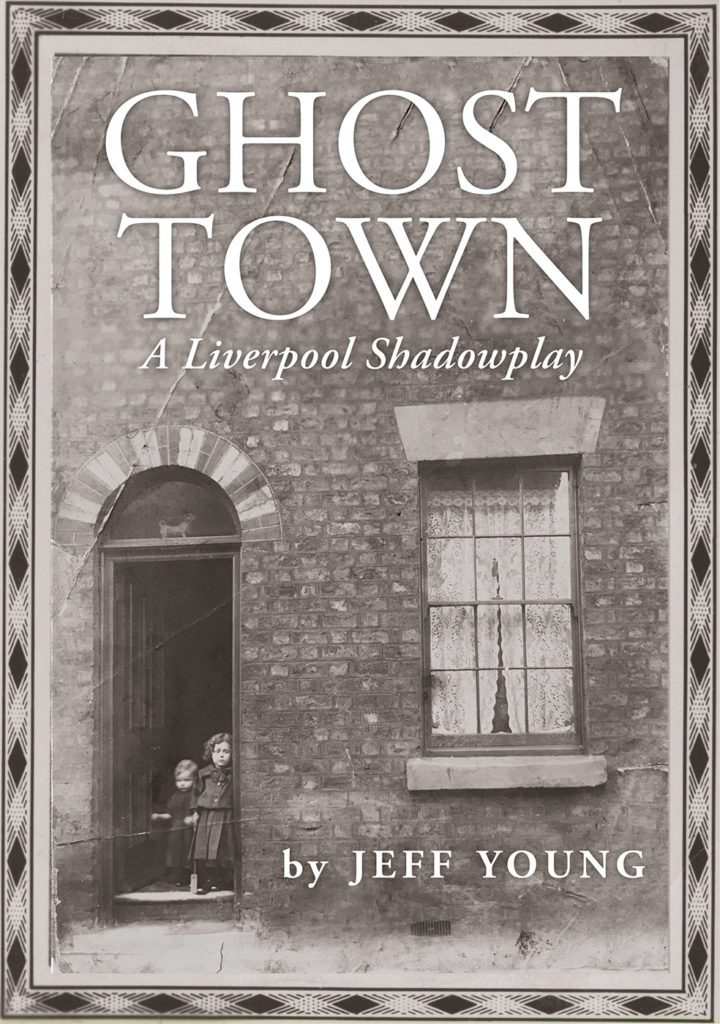

Jeff Young has long been fascinated with Liverpool, its history and how it intersects with his own life. In his new book Ghost Town, published by Little Toller, he explores his own experiences and the life of the Liverpool, taking journeys through the city and away from it, creating new ways of mapping his home town. The following extract comes from the chapter titled ‘Shadow Boy’.

Down the canal, a shadow-boy follows me, scrawny, in a dirty school uniform. His face always looks tear-streaked, as if he had been crying and has wiped city dust across his face with a sleeve. And he looks tired all the time, the sort of boy who falls asleep in Geography and gets slapped with the back of Mr Ashby’s hand. Sometimes I see him skulking in the park near our house, by the swings where some lads burnt their school uniforms after they were expelled. When he sees me looking he sticks two fingers up, a fuck you to the world. His name is Billy Casper.

I found him on the cover of a book. A Kestrel for a Knave changed everything. Every month I would order a book from a school reading magazine. I’d never heard of Barry Hines but I liked the sound of the story and the catalogue had a picture of a kestrel on its cover. The Observer’s Book of British Birds was one of my favourite books and I recognized the slate-grey and brown hawk, even knew its Latin name, Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus. But when the book arrived it had a different cover, a grainy photograph of a boy with a hacked-at haircut and the two-finger salute of the insolent truant. He looked like half the boys I went to school with; he looked like me.

‘Billy Casper is a boy with nowhere to go and nothing to say.’ As I started to read the book I began to see him everywhere. He was a shadow by the lock-up garages. He was a kid helping the milkman, riding on the milk float and spitting in the empties. He was the rough-arsed kid following me down the canal and dipping for tropical fish in the Hotties where the Tate & Lyle factory spewed hot water into the cut. On an enforced cross-country run across the fields I saw him hanging on a tyre swing underneath a half-built motorway bridge. In bed at night I looked around my room and ‘the window was a hard-edged block the colour of the sky … the darkness was of a gritty texture. The wardrobe and bed were blurred shapes in the darkness. Silence.’ My bedroom was just like Billy’s room at the start of the story, except that my room was full of books. I don’t think it had ever occurred to me that people from the north wrote books.

Barry Hines led me to Alan Sillitoe. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning might be the first grown-up book I ever read, apart from sneaky reads of my dad’s Harold Robbins and Len Deighton books. I read Billy Liar and laughed as Billy dumped the calendars he had forgotten to post, reminding me of the rainy day I got fed up lugging my paper sack and dumped fifty Liverpool Echos behind an electricity substation. I borrowed – and never returned – Stan Barstow’s A Kind of Loving and I recognised my future – my intended future – in its pages. I was a boy who would flunk out of school and be sent by the dole to a filing-clerk job at the Council. The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner inspired me to stop running just before the finish line on a district sports day, the act of defiance that finally got me kicked off the cross-country team.

Billy Casper was roaming the fields and I went with him. We were invisible boys. No one in school or at so-called Careers Day cared if we existed. Until I met Billy I don’t think I’d ever even seen a hawk, but in some way my passionate obsession with art and books was similar to Billy’s identification with a bird. It mattered, and that meant that I mattered and so did my desire to create. When Billy flies the hawk he discovers new things about himself, things that were buried inside like dignity, native intelligence, love, hope and spirit. When I saw the film version of the book it almost exactly mirrored the boy and the world I had imagined. My life was being transformed by an act of imaginative engagement.

We went on a school trip to the Odeon in Liverpool to watch Kes, the film of the book. My book! John Cameron’s music was beautiful; bird in flight, soul in flight. Listening to it fifty years later it still moves me to tears. Flutes and clarinets, fragile creatures, airborne. It is the music of Billy’s dreams, soaring across the fields on thermals of longing, just beyond his reach. After seeing the film, whenever I read the book I could hear John Cameron’s music. In a way, it has become the soundtrack to my own childhood. When I picture myself as a fourteen-year-old boy I hear the fragile call of Harold McNair’s flute.

David Bradley is Billy Casper. I feel like I’m sitting in the classroom, listening to him talking about the bird. I look at the faces of those boys at their desks, watching them slipping under Billy’s magical spell. I look around the cinema and the boys on the school trip are interchangeable with the boys on the screen. I will never know what it’s like to fly a bird, but I do know what it feels like to discover I have dreams.

Many years later I made a Radio 4 drama documentary called The Hunt for Billy Casper. I went on a journey around Britain and spoke to the author, Barry Hines, and the director of the film, Ken Loach. I visited the school that Billy Casper reluctantly attended and it looked exactly like the school where I spent my invisible five years. Barry Hines took me to the farm where Billy climbed the wall to steal the hawk. I could see Billy clambering up as I stood there with Barry and my producer Melanie Harris. I felt I was both communing with Billy and exorcising my identification with him. The final stop on my journey was to a semi-detached house in Catford where I spent a day with David Bradley, the actor who played Billy Casper in the film. He was now a middle-aged man, perhaps damaged by his experience of playing Billy Casper; he had never worked out a way of living his own life. He was politely bemused by my pilgrimage. I couldn’t quite explain to him why I was there, nor what I wanted from him. I was shocked to hear him speak; he no longer had that beautiful Barnsley accent. His short-lived career as a stage actor had replaced that voice with a middle-class tra-la-la. We drank tea and he talked about backgammon tournaments. He would always be Billy Casper but I got the impression he no longer knew who he was. It troubled me that I’d bothered him and we left him there in his garden, listening to the birds. I asked each person I interviewed where they thought Billy Casper went after the book ended; every single person said, ‘Nowhere. He’d have spent his whole life on the dole.’

On the edge of our housing estate was the wilderness. Here there were forests, caves, a lake where the golden knife-fish swam, and a black mountain where wars were fought between rival armies. The forests were made of stunted trees, weeds, spud plants and grass that towered above our heads, through which labyrinthine paths were trampled on commando raids to seize the enemy’s weapons. The caves were down the transit camp manhole covers; we would crawl through shallow tunnels beneath stalactites of rusted pipes and electrical cables, over heaps of fly-tipping, scabbing our knees and elbows as we crawled, trying to get to the holy grail of looted treasure rumoured to be stashed in an abandoned fridge. The lake was a stinking bomb crater where we’d float ships of scaff planks and floorboards. When bulldozers and dumper trucks came and started levelling the transit camp we waded into the malarial water. With battered old Dulux tins we scooped fish out of the dirty pit as bulldozers filled the flooded hole with rubble. Recklessly I’d defy the bulldozers, holding up my paint pot full of tiddlers and goldfish. Fish like gold and silver flick knives with miraculous powers to protect the catcher.

Our war was a territorial dispute. To begin with, the ammunition was the fruit of flowering cherry trees. Then it was pea shooters. Then rocks. Running battles were fought for the possession of Black Mountain, the enormous mound of earth piled up by the bulldozers. Vietnam bled out of the television and into my violent imagination. My army was always the Viet Cong and we were ruthless in combat. We even practised rock-throwing at pop-bottle targets, shattering glass all over the gravel in front of the lock-up garages.

The Miller boy had a stash of oil-drum lids hidden in his coal bunker. They were shields for his army of Catholic school boys, stockpiled for the war against the new kids from the slums. I gathered a rebel force and we’d sneak down back alleys, over the backyard fences and into Miller’s yard in the dark, stealing his oil-drum lids and sharpened mop handles and whooping like mercenaries and thieves. This was ecstasy, this was revolution. We were the new-kid scum and we had made our mark. We built a hideout of plastic sheeting, corrugated iron, asbestos sheets, planks from old barns and milk crates. We made guerrilla dens in lock-up garages, smashed-up bus shelters, flyover hideouts, the Nowhere Land of detritus where lives had been forgotten and discarded. There was nothing restorative about the landscapes I was walking through during this time or any other.

Billy Casper comes with me on my raids. Sometimes I go with a gang of lads to kill the cocky watchman. The old man sits there at his brazier, warming a tin of beans. We take table legs and cricket stumps and run across the building-site ditches, edging as close to him as we dare, quiet as we can be. One night I get so close to him I can reach out and poke him with my stick. He hunches there, smoking and spitting, slurping his stewed tea, poking the coals in the brazier. We always say we’re going to kill him, but we always sneak away. One night he sees us skulking and throws burning timber at us; we run away terrified but laughing with the thrill.

We made folk devils out of complete innocents. An old woman who lived in a rundown cottage by the swing bridge became our Ginny Greenteeth – the Liverpool name for Jenny Greenteeth, or Wicked Jenny, the folklore river hag. Everybody knew she spent the nights beneath the water; she was a river witch, a canal hag who grabbed children and drowned them under the green pondweed. There were dead children on the bottom of the canal, weighted down and trapped inside the cages of shopping trolleys and pram frames. Ginny Greenteeth, the grindylow, had imprisoned them there in a larder that stretched halfway to Leeds.

The best of our folk devils was Fred Wilde the painter, who lived in a cottage by the dual carriageway and exhibited his abstract canvases in his front garden. His works were like migraines in paint, mad vortexes and mind-storms, aggressive geometries, psychotic weather. I remember him as a mad, wild-haired prophet. Once a year he exhibited his work at the local art society amongst the pastel Lake District landscapes and watercolours of flowers. Sometimes we’d climb into his garden and peek in through his windows. We couldn’t frighten him because he was more frightening than any of us. Towards the end of his life he abandoned his Kandinsky rip-offs and settled down to paint quaint memories of cobbled streets and chimney sweeps: Lowryesque nostalgia. His house was demolished soon after he died, as if he were being exorcised for disrupting the dull conformity of the highway verges. Sadly, his work does not live on.

Down the canal by the strawberry farms a boy called Doyle gets off his bike, flips open a packet of cigarettes and passes one to me. I hold it in the V of my fingers, trying to look as if I know what I’m doing. He passes me the matches and I light up and suck hard, pulling the smoke into my lungs, feeling the instant dizzy hit. And then, using his teeth as a bottle opener, Doyle takes the top off a bottle of brown ale, gulps half of it down and passes it to me. I know a bit about drinking – thanks to nana I’ve been drinking rum since I was three years old. As I sip the ale Doyle tells me the history of the dirt. ‘All these fields, far as eyes can see, are deep in human shit. Night soil from Liverpool. One-hundred-and-fifty-years-old shite. The spuds you eat, the cabbages, the strawberries, are grown in human shite.’ More than 150,000 tons of human waste was transported down the canal from Liverpool every year, I learnt, mixed with rubbish and coal-fire ash and dumped on the fields. The new town was built on Liverpool’s sewage. Doyle gets back on his bike and cycles away, leaving me there with half a fag and the dregs left in the bottle. It’s beautiful here in the watery, washed-out fens. The geese are flying over the fields. Sunlight glints off glasshouses, lights flashing like secret signals. Fat water voles – we used to think they were rats – drop into the canal and swim through the submerged wreckage of milk crate and pram. Sometimes I sing Billy Fury’s ‘Wondrous Place’ and think about the beauty. I found a place full of charms, a magic world in my baby’s arms.

The rough field with the abandoned buses is turned into a park, with swings and a slide and green grass for football. I miss the buses, miss climbing in amongst the manky paint pots and pretending to drive to Oklahoma. I miss the transit-camp ruins and the burnt barn. The sandy brook gets diverted into concrete pipes and more houses get built. It looks like anywhere else, and I have to go further to find my wilderness. Once I went on a voyage up the canal on the skinheads’ polystyrene raft when they were away on some territorial skirmish. Bits of the raft, like globby white eggs, broke off and floated away on the canal murk. Once I followed a weather balloon that looked like a silvery UFO all the way up to some hills I’d often seen in the distance. I realised when I reached the hills that I was now in the distance; I’d reached the far away.

Even then I was a watcher. I would sit in the middle of potato fields and watch the enormous blue and grey sky that would pour into me and change my weather. I loved the geometric lines of the drainage ditches stretching into infinity. I loved that the canal – a graceful meander following the contour lines, a road made out of water – was made by men. One day I will go to Holland and I will know exactly where I am because the fields and fens of the Netherlands will look exactly like the fields of my marauding days. Sometimes the world seems to tilt in such a way that I can see the Irish Sea in the distance.

At night, I lie in bed and read A Kestrel for a Knave. I have begun to realise that my life is very different to Billy’s; what we do have in common is a scrapheap education and a sense that we will have no say in our own futures. Billy will go down the pit or on the dole. I, too, will go on the dole as soon as I leave school, and then on to the Council. Billy’s fate is written for him by his author, Barry Hines. But Hines had based it on the truth: boys like Billy were doomed. And so was his hawk.

It had stopped raining. The clouds were breaking up and stars showed in the spaces between them. Billy stood for a while glancing up and down the City road, then he started to walk back the way he had come.

When he arrived home there was no one in. He buried the hawk in the field just behind the shed; went in, and went to bed.

And that’s the way the book ends; harsh, blunt, the plain facts. The hawk is dead and so are Billy’s dreams. Downstairs in our living room 500,000 anti-war protesters are gathering outside the White House singing John Lennon’s Give Peace a Chance; Apollo 12 is heading for the moon, and a Soviet submarine is colliding with an American submarine. I go to sleep imagining the end of all known things.

I wake up in the night and am still alive. None of us has been killed. There are no tanks on our streets, no guns. There is no napalm in the trees, no burning oaks. There are no mushroom clouds over the houses, no bodies reduced to ash. We have surrendered Black Mountain and the war is back inside the television. Once again in the quiet of night my mother tiptoes into the room I share with my sister Val and opens the bedroom curtains. Over the rooftops, all around the chimney pots, I watch the shadowplay of owls.

*

Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay is out now and available here, priced £16.00.