In a time of weirdness and worry, Jon Woolcott finds comfort his father’s childhood books.

At the beginning of March, on the westwards edge of a Cotswold escarpment, I crawled through a small hole in the ground and into a Neolithic burial mound. Scrabbling on my hands and knees under the lintel stone I felt my way into the dark. Beyond a short, low passage, with the help of my phone’s torch, I found three small chambers, each one large enough to crawl inside and sit. I rested my back against the stone and earth and my fingers touched the edges of the small space, the voices of my companions outside muffled. This was an intensely private archaeology, a clambering into history. But it was also a moment that was essentially of the present, of the right now, to be alone and able to see no-one, and for no-one to see me. Those moments felt, then, like a precious rarity.

This episode was part of a new tradition: four of us and a dog on a weekend to somewhere a bit off the beaten track, and somewhere between us in Dorset and Mike and Preds in Powys. This year we chose the scruffier part of the Cotswolds, stayed at a pleasingly rowdy pub in Stroud — a proper working town with the relics of its industrial past everywhere — and we walked the Slad valley. On a ridge we found a ritual landscape: a semi-circle of disused caravans, and further on an old quarry at the top of a hill close to the Laurie Lee Walking Trail. One evening and only a couple of drinks in, we took a towpath down the wrong canal on the way to a pub for dinner, realising our error by degrees as we left the lights of the town behind. We took only slight pleasure in teasing Mike, the author of a book about maps and another about footpaths, for his map-reading skills. It was dark, after all.

The weekend was snatched, just in time, from the grip of the inevitable; this last trip away is vivid, burning brightly in the memory. Since then, like everyone, I’ve mostly been at home in this new time – what I’ve termed the Worryweird. The world has shrunk. I now rarely use my bicycle, which is how I usually explore, how I find things out. Instead of day-long looping and uneven ellipses from home, my few recent rides have been a reeling in; short, mostly circular meanderings through surrounding villages. Instead I’ve walked, alone and at lunchtime, and half an hour away from my desk means I can’t get far. It doesn’t matter: the landscape here has always held me in its grip, partly because it is intrinsically eerie. The flat land offers no refuge, no place to hide; I stick to the field margins next to the hedges and wander under the boundary oaks that lend shade to cattle in summer. Woods and forests may be the more traditionally ghosted landscapes – there are none of those here, but the spook is real enough. The cows have been outside only a few weeks, the massive beasts displaying such obvious delight at their pasture after months locked in, just as our lockdown started. Here I’ve always felt a little distant from the world’s events, but aside from the sharpness of the spring birdsong, it still feels noticeably quieter. In her terrific evocation of four landscapes, Limestone Country, Fiona Sampson writes of how noisy La France Profonde really is – full of chainsaws, shouts, shots and traffic; the new silence has made me appreciate that usually Dorset is little different. Agriculture continues, tractors rumble and spray tiny pellets of white fertiliser, the fields still bleat with lambs, but everyone has noticed the hush, judging by shouted semi-conversations with neighbours as they pass my gate on foot. I see no-one when I’m out. The land is emptying.

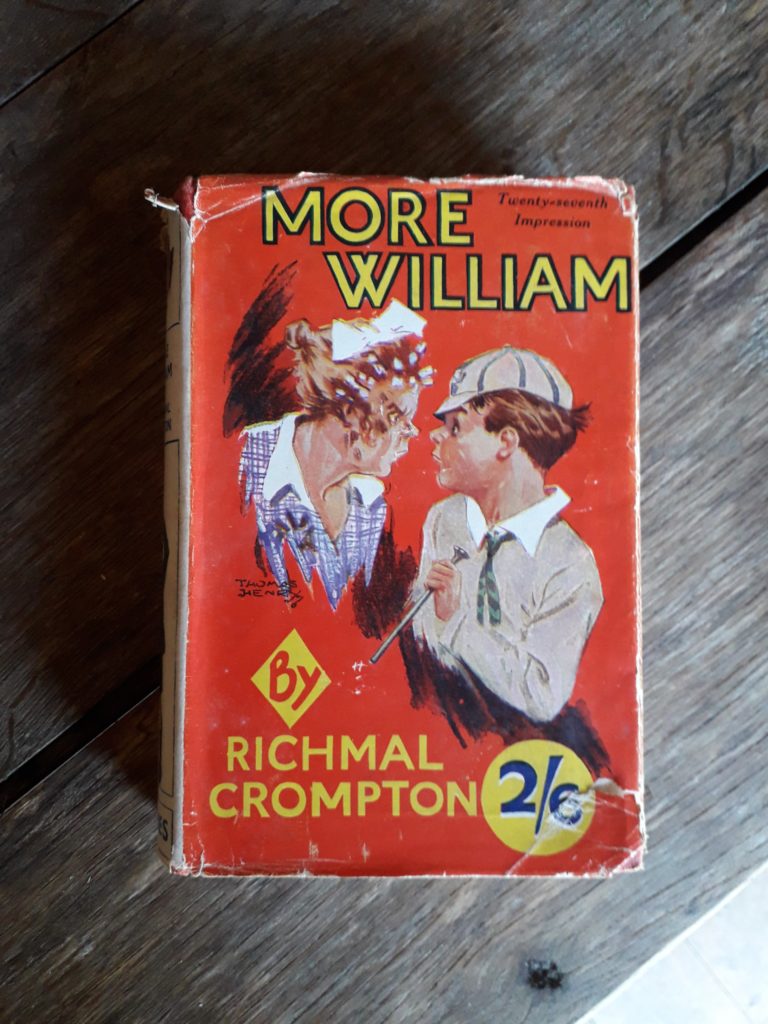

At home in the Worryweird I turn to books, not to the unread pile at the bedside but to the shelves in the spare room. My father kept all his books from childhood, and I’ve ended up with them. A collection of small leather-bound classics: Dickens and Thackeray and Austen and the Brontës, and they appear to be mostly unread. More obviously thumbed were the Just William books by Richmal Crompton, in their 1930s hardback Newnes editions, some with dust jackets, just. If I’m honest these books always left me rather cold; maybe I was too obedient a child to feel much empathy with the noisy little oik. Although I’m inconsistent, being fond of the stories of Molesworth and St Custard’s, probably because I’m a little too close to the school sissy, Fotherington-Tomas (“Hallo Birds! Hallo Sky!”). Most of all I adored Winnie the Pooh, first published in 1926, the year after dad was born. His edition is a stern looking hardback in faded green boards, mine was a jolly Methuen paperback from the 1970s. I wanted to creep inside the expansive but safe world of the 100 Aker Wood, populated by mostly friendly creatures, and as an arch sentimentalist, I still find the closing paragraphs of The House at Pooh Corner one of the most poignant passages in literature. Amongst dad’s book collection, always obvious because its long shape protruded from the shelves, was an odd annual from The Daily Chronicle, which collected cartoons depicting Japhet and Happy. Happy was a bear who never spoke, Japhet was a wooden boy with no hands and strangely articulated legs and arms, without elbows or knees; the son of similarly-limbed parents. Despite identifying as toys the family lived on a street rather like ours. Being from a newspaper, the cartoons were in black and white, but the annual’s cover was a bright yellow beach scene. The jokes, such as they were, were mild and inconsequential, but still the cartoons were a peek into a child’s imagination. I was gripped by these comic strips, read them over and over, spell-bound by their combination of normality and strangeness. It never occurred to me to ask my father what he had thought of them as a child, forty years earlier, until it was too late. In one strip Japhet, mostly an indoors sort of boy like I was, takes a walk at dusk in the park. Every leafless tree looms over him, a horrible spectre with a shrieking face in its trunk, branch arms and long twig fingers reaching for our cowering hero. Look, they seem to say, we have fingers, even if you don’t. Japhet resolves never to return to the park, scared now of nature. This was no 100 Aker Wood, and Happy in his silence was no Pooh gently taking Piglet’s hand, or mine. This was sometimes how I experienced the outside as a child: unpredictable and vaguely threatening beyond the back garden, where a factory hummed all day beyond a chain-link fence. Everything beyond trembled with danger. The inherent threat of the outdoors was rarely realised, although I was once knocked over by a curious New Forest Pony and refused to be comforted by an aunt.

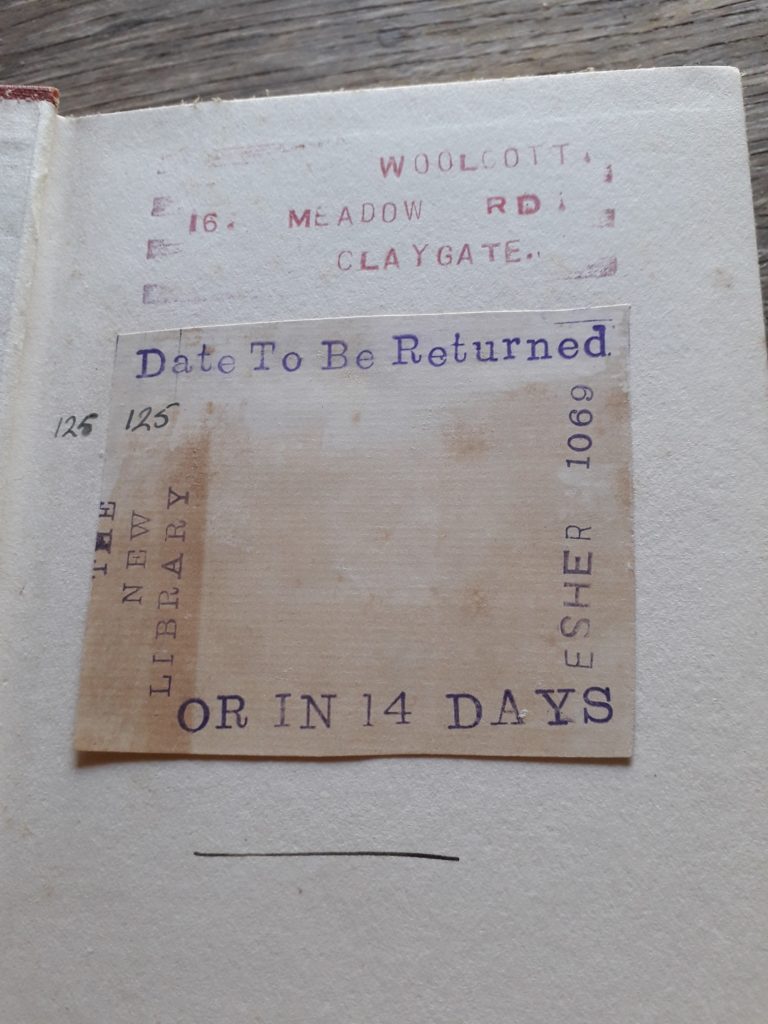

Home and old books – in this new confinement they have an easy familiarity with one another. The books represent continuity and stability – they survived a world war, upheavals, moves, my parents’ deaths. Leafing through them I found something which pricked my eyes. On the very first page, even before the title page was a rubber stamp mark, inked in red:

WOOLCOTT

16. MEADOW RD

CLAYGATE

I imagined my dad, without brothers or sisters, carefully pressing the little squares of rubber together and rocking the stamp as he pressed it onto the paper. It was a normal, proprietorial thing to do. But there was more. Beneath the stamp and in almost every book was glued a square of paper, with lettering, this time in purple, inked along the four sides reading:

Date to be Returned

The New Library

OR IN 14 DAYS

ESHER 1069

My father had created a lending library from his books. He wanted to share them, and he wanted to have them back afterwards. But in none of them could I find a date stamp – The New Library had issued no books, not to a friend or a parent, nor to any of my stern black-clad Victorian great grandmothers or great-great aunts whose fierce, war-torn faces appear in many little photographs. His little boy’s world was small, but he’d tried to enlarge it.

Outside, life in the Worryweird is growing smaller; I think that I am beginning to resent the intrusion of what was previously normal. I’m pacing around my home patch, looking up rarely, a slow turning over of what I already know, a contemplation. Before all this, occasionally and always in summer, I’d walk at dusk or in the night and relish the moonlight. It was a way of dispelling the landscape’s threat, possibly because I had become the feared, the unknown. But now we might all be the terror, day or night makes no difference – each one can make a ghost of another.

Now too, sleep is sometimes harder than usual. I’ve recalled a reliable fantasy from my youth to welcome it: I would dig a shallow hole scraped from loose earth on the edge of an imaginary forest and cover myself with planks and brush and was hidden and safe. In recent weeks, the memory of the Cotswold burial-mound has re-woken this useful encouragement, my younger self has lent me rest. In daytime contemplation and distraction have come from another excavation. My father’s books, his accidental grave goods now unearthed, have revealed the interior life of an only child in a Surrey village eighty years ago, and how he spent his days with little inky fingers, stamping books for the readers who never came.

*

Jon Woolcott lives in north Dorset. He works for the publisher Little Toller, and for Cranborne Chase AONB. He is writing a book about the hidden and radical histories of the south of England.