In his latest photo-book Halls & Oats, Jethro Marshall turns his lens on the village halls of East Devon and West Dorset — and in doing so, emphasises just how much hides in plain sight, writes Alistair Fitchett.

I first came across Jethro Marshall’s photographs in a copy of the fabulous Modernist periodical. Black and white shots of concrete interventions in the coastal landscape, including one of industrial dentistry in the cliffs of Beer which I recognised straight away. The photographs would have pulled me in regardless of their geographical context, but there is always something special in seeing others seeing our local landscapes as we do. Human connectivity, even that which is based solely on the framing of scenes in a viewfinder, would seem to be a basic instinct. It needles us even as we relish our aloneness and revel in our perceived otherness, and it can be a strangely comforting itch.

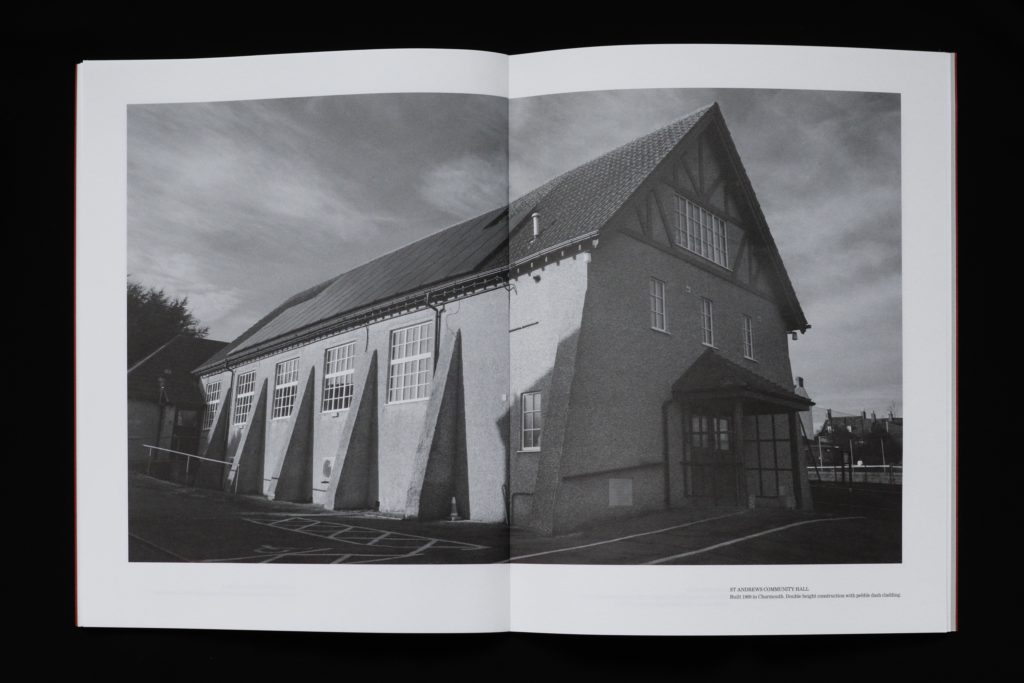

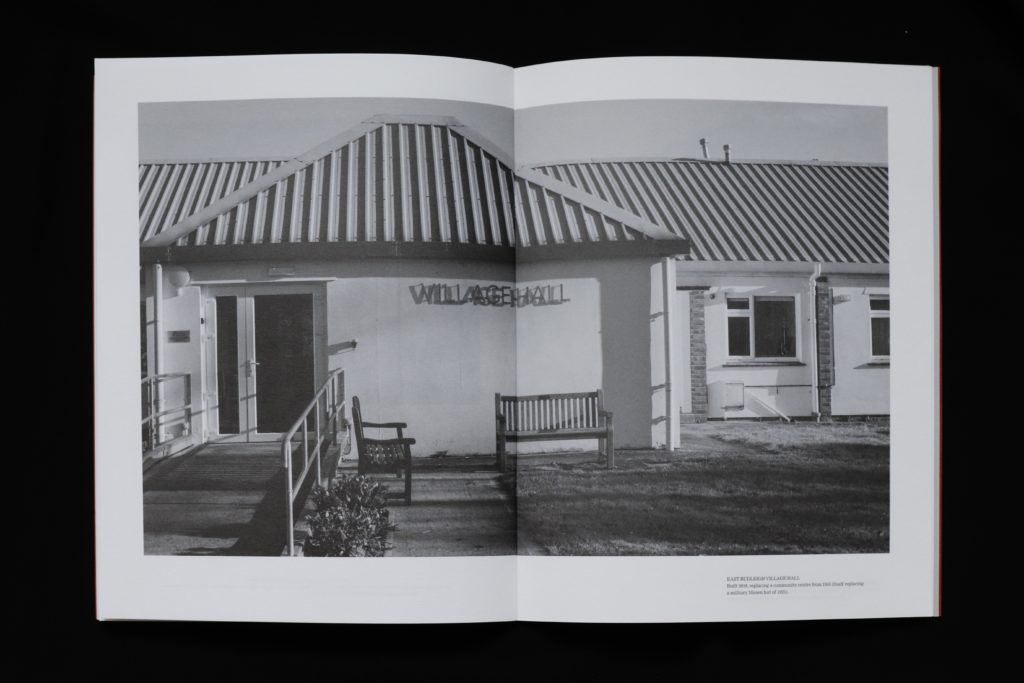

It is a delight, therefore, to see that Marshall’s latest book Halls & Oats (published through his own West Country Modern imprint) continues to weave these threads, collecting a range of village halls from the borderlands of East Devon and West Dorset. Like a monochrome magical mystery tour of the country lanes, Marshall shows us the vast range of character within such an apparently limited specificity of building (one hesitates to call it architecture). Here, Branscombe’s severe blank white face of blockwork bookended with natural stonework, there Corscombe’s former Victorian school in sandstone approached by the concrete battlements of a 1994 ramp. Martinstown’s hall meanwhile looks for all the world like an uninspired builder’s bungalow wrapped in stone cladding in a misguided attempt to blend into a mythical rural aesthetic, whereas Knowle’s village hall which closes the book is almost unrepentant in its concrete prefab utilitarian honesty. I have passed the Knowle hall innumerable times on my bicycle rides to Budleigh over the years, and each time I have nodded to it in recognition of its perfunctory stance. It’s nice to see that someone else has paid it attention. Marshall notes that whilst it was erected in 1948 it did not actually get planning permission until 1964. This lawlessness only makes me warm to it more.

In recent times there seems to have been an explosion of reference to liminal landscapes and spaces. Places in between. Points outside this or that. Nowhere lands visited by nowhere people. It strikes me that the buildings and spaces Marshall photographs are such as these, specifically in the way that they are presented in entirely un-peopled forms. In this, Marshall’s work neatly encapsulates the magic and deceit of photography. Like John Myers’ masterful photographs to which Marshall clearly nods (check out Myers’ ‘Looking At The Overlooked’ and ‘The World Is Not Beautiful’ collections), these photographs whisper ‘look at the emptiness’ whilst simultaneously throwing the cloak of invisibility around the photographer themselves. The photographer is like that murderer dressed as the mailman in the Father Brown story, picking up and running with Poe’s notion of the individual hidden in plain sight. These are not empty, unpeopled spaces, yet by photographing them as such Marshall (like Myers) magically makes us acutely aware of our humanity, by and for whom these spaces are constructed. In other words, we may not need to see the details to understand the detail; to know that lives imagined are as real as those we see.

*

You can buy various Jethro Marshall works, including copies of Halls & Oats, here.

Visit Alistair Fitchett’s blog here. You can also follow him on Twitter and Instagram.