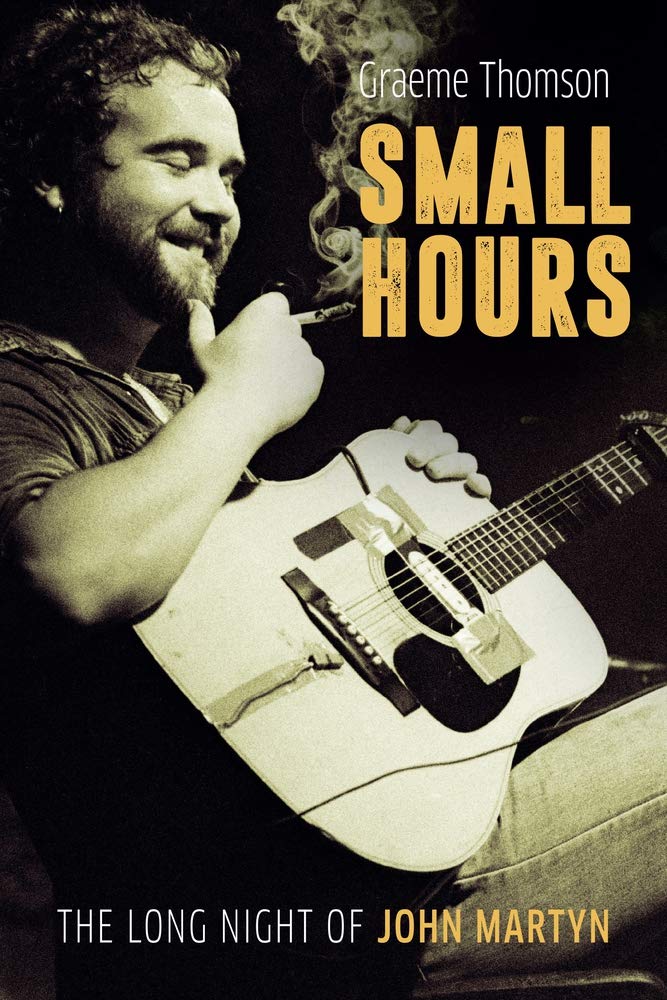

Andy Childs reviews Graeme Thomson’s newly published account of the revered guitarist and songwriter’s tumultuous life and times.

One day early in 1974 I stepped off a train at Hastings station and made the short walk to a pub on the coast in the Old Town. As editor-in-waiting at Zigzag magazine, I was there to interview John Martyn. We’d arranged a late morning rendezvous at the pub and sure enough Martyn was there, with his faithful sidekick Danny Thompson, and after a couple of pints and a game or two of snooker Martyn and I strolled up along the narrow, winding streets to his house where, in his living room, we spent the rest of the afternoon with his albums spread out on the floor, talking about his music and his career to date. It was one of the most rewarding and enjoyable interviews I’ve ever done and when, as the light faded, we made our way back down to the pub again to rejoin Danny Thompson in more drinking and, from my point of view, a disastrous game of darts, I felt that I had learned more than I’d expected of this maverick musician and his wonderful music. John Martyn, that afternoon, was charming, very friendly, open, generous, funny, and great company. A delight to be with. So I guess I can count myself lucky that I caught him on a good day, because as Graeme Thomson candidly describes in this excellent and thorough biography, Martyn was, besides the creator of some of the most beautiful, cerebral, pioneering music ever made, a deeply tempestuous character, prone to periods of violence, extreme bellicosity, and alcohol-induced mayhem.

Born Ian David McGeachy in Sept 1948, his parents split up two years later when his mother left the family; a fracture that Martyn, perhaps a little disingenuously, considers responsible for the subsequent flaws in his character. He lived in Scotland most of the time with his father and strict — but loving — grandmother, and with music as an ever-present backdrop to his early years he soon took up, and started to excel at, the guitar. He was also academically very bright although his nascent rebelliousness meant that the folk scenes in Glasgow and Edinburgh were ultimately more attractive than the classroom. He left school in the summer of 1966, aged 17, took a couple of unsuitable jobs that didn’t last, and by the end of the following year he’d upped sticks to London and was a regular at Les Cousins folk club. He changed his name to John Martyn and his youthful good looks, unconventional guitar style (he often used a series of unique tunings), natural brashness and irreverent approach to folk music conspired to fast-track him to wider recognition — not with everyone’s blessing it must be said — but it brought him to the attention of influential people like Theo Johnson, Joe Boyd and Chris Blackwell, and the result was a licensing deal with Island Records for his first album, London Conversation. His relationships within the music business were intense and turbulent, as was his uncompromising attitude towards some of his contemporaries, but in Blackwell he found a loyal believer who stuck with him through unspectacular album sales and personal upheavel.

His ill-fated marriage to, and uneasy musical alliance with, Beverley Kutner preceded what was arguably Martyn’s most fruitful and creative period. Between the end of 1971 and the beginning of 1975 he released four spectacularly good albums – Bless The Weather, Solid Air, Inside Out, and Sunday’s Child — records that were innovative, exploratory, warm, containing the most beautifully tender, soulful songs and as far removed from ‘folk music’ as it’s possible for one man and a guitar to be. When I sat down with him that afternoon in 1974 Inside Out had not long been released, and Martyn was searching for a drummer to complement the instinctive musical empathy that he’d developed with bassist Danny Thompson so that he could perform his groundbreaking music live. I’m not sure he ever managed to assemble his perfect ensemble, but he and Thompson developed a profound musical and personal bond that resulted in many memorable performances — and perhaps an equal number of offstage incidents that set new standards in wild, destructive behaviour and alcoholic belligerence. Frustratingly, as the years rolled by, the albums became more and more patchy as it seems his behaviour and temperament became increasingly aggressive and, for friends and family, almost totally alienating. His treatment of Beverley and his children was especially cruel and vindictive, although despite subsequent up-and-down relationships and a seemingly more contented last few years of his life, he claims to have “never written a great song since Beverley finally left him”. I would agree. By the time he passed away in January 2009 of pneumonia and acute renal failure, he’d managed a certain degree of reconciliation with his children — though apparently having no regrets about the way he’d behaved or the emotional havoc he’d caused through the years.

There were many other colourful and significant people in Martyn’s turbulent life – Hamish Imlach, Nick Drake, Phil Collins, Ron Geesin, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry to name but a few; Thomson deftly weaves them into the narrative and by doing so places Martyn and his music in context. His peers were undoubtedly in awe of him and his talent. That he never really achieved the degree of universal recognition that his music deserved remains a mystery to me and I have to say that, thankfully, despite the plethora of awful, wince-inducing anecdotes, my love of his very best music has never waned. So I was greatly looking forward to this book and am grateful to Graeme Thomson for telling Martyn’s story with incisiveness, compassion and even-handedness. Small Hours is the perfectly balanced book that John Martyn, his music, and the people who knew him, deserve.

*

Small Hours, published by Omnibus Press, is out now. You can buy a copy here, priced £20.00.