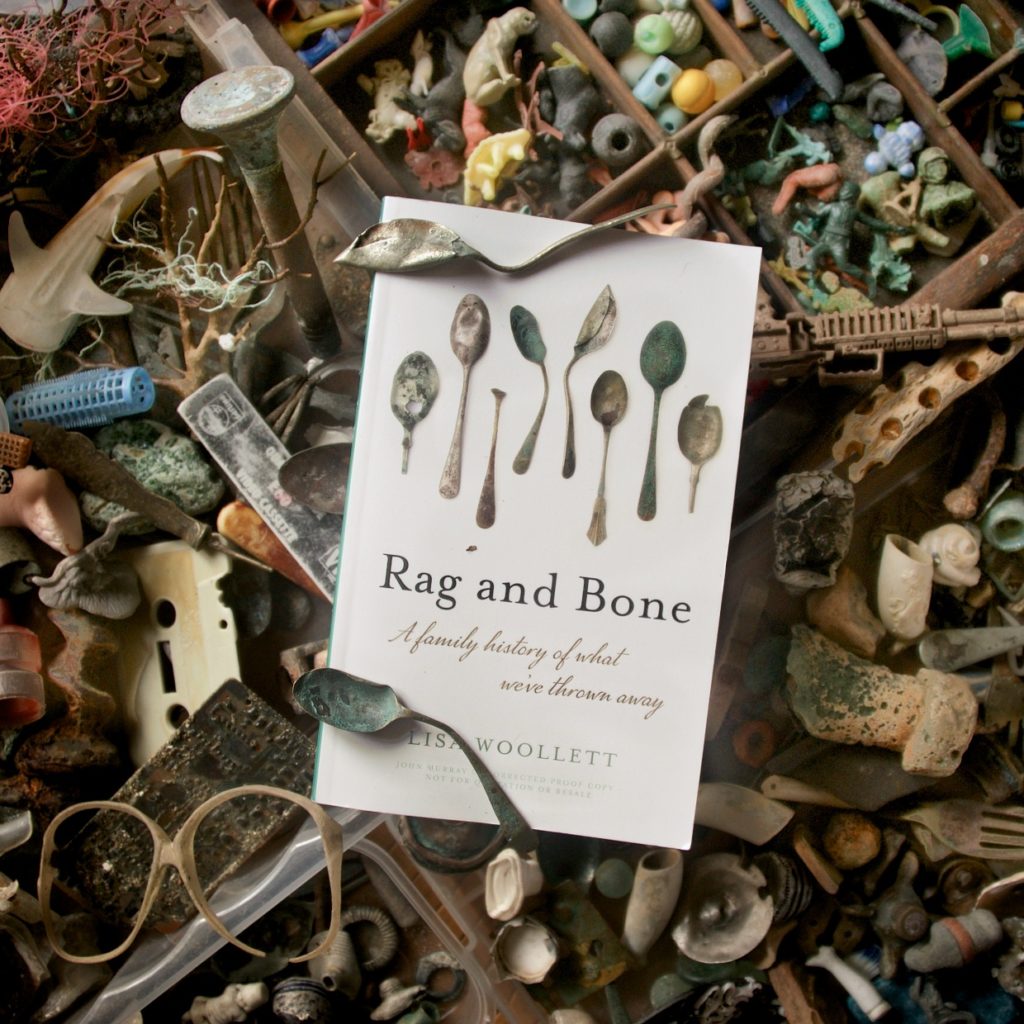

An extract from Lisa Woollett’s Rag and Bone: a family history of what we’ve thrown away, which is our Book of the Month for July.

Driving back along the marsh road the following evening, I slowed down for a better look at a barge wreck. Like others, this would originally have been hulked at the muddy creek edge, perhaps after the brickworks closed, but in the stillness of this quiet backwater the saltmarsh was encroaching seawards. So, unlike the blackened hulls out on the mudflats, this one appeared to have beached on dry land. Silvered by the weather, the last of its exposed timbers were gradually sinking into pillows of cordgrass, settling down to become part of the marsh’s creeping advance.

I was glancing back for one last look when I saw the couch. Down on the saltmarsh below the road, it was blue and facing out towards the estuary. In Cornwall I occasionally come across incongruous chairs in the middle of nowhere – often facing out to sea – so my first thought was that it had been put there for someone to sit and look out at the view. I grinned and pulled over. In late sunlight, the verge was a wall of cricket song. Feeling tired from sleeping on the driveway, I poured the last of the flask’s tepid coffee and headed out to the couch. It was only as I sat down that I saw the matching chair face-down further out, and realized they’d been fly-tipped. There was even a stereo rusting in the mud.

I shifted position so it was just out of sight. The rubbish wasn’t a surprise, though, as from the layby the previous day I’d glimpsed a heap of wet carpet and several bald tyres. Unlike the litter in the layby verges, these were things people had driven out here specially to dump. As it has for centuries, the relative remoteness of the estuary marshes still suggests an obvious ‘away’.

light switch, wren farthing (1937-1956), fy button, zip pull, model propeller,

death’s head button (single hole), curtain runner, safety pin and a police

shoulder number.

Taking a similar route to the Bovril Boats and ‘rough stuff’ before it, London’s twentieth-century rubbish also flowed east along the Thames into Kent and Essex: downriver and down-wind. While landfill remained a cheap and easy solution to the problem of burgeoning waste, London boroughs continued buying up marshland along the estuary to bury it. At the time there were few concerns around siting the dumps near water, on Britain’s coasts and low-lying estuaries. In the Thames Estuary alone there are thought to be more than fifty disused sites at risk of flooding and erosion, with a number that have already breached. Over the water at Tilbury, vast swathes of London’s historic waste can already be seen hanging from wave-scoured riverbanks and scattered on shore.

Earlier in the year I’d taken my mum to visit an eroding site with me. As I’m happy to spend hours searching, I’m often wary of taking anyone along, but from previous trips I knew that some of the finds were likely to date from her 1940s and 1950s childhood. The forecast that day was bleak, with an emphasis on wind-chill, but as we stood in the car park piling on extra layers and waterproofs, I was hoping for finds that might spark memories of those post-war years. As the 1950s in particular saw another big shift in British attitudes towards consumption and waste, I also hoped to find traces of those changes on the shore, with the eroding landfill exposing its once-buried record of an era.

The dump’s contents had been washing out onto the shore for over a decade. Our first glimpse was from the steps leading down to the concrete sea wall and there, sheltered as we were from the wind, when the sun came out it was almost warm. I glanced over at my mum and she pulled a face: at our bulky, overdressed gait; at the sound of rubbing waterproofs over too many layers.

As beachcombing is often best during inclement weather, more than once I’d trudged down those steps in the rain. A few months earlier it had been with my eleven-year-old daughter, when the two of us spent a couple of hours grubbing about on the shore with freezing hands, our jeans stiff in the wet, her red hair plastered to the outside of her hood (but all was well as she found blue poison glass and a fool’s-gold fossil).

seventeenth – twenty-first century. Shown with the waste from making bone

buttons or beads by hand, with each half-circle the space where one was

removed.

On reaching the beach below the dump with my mum, it was clear that the cliff falls were fresh. The clay was sodden and slick, with a glistening layer still covering the stones at the top of the shore. Its undulating surface had been sculpted by recent high tides and was studded with broken pottery and glass.

*

Rag and Bone is out now, published by John Murray, and is available here, priced £20.00.

Read Frances Castle’s review of the book here.