In Wales, over the first 12 weeks of lockdown — when birds were given back their spaces for a time — James Roberts watched curlews circle the uplands, swans nest on pools, and goshawks appear for the first time in the wood he’s walked for two decades. Inspired by this, he produced a sequence of poems, ‘WINGED’, which interweaves ideas about wildness, fragility, hiddenness and withdrawal. Miriam Darlington reviews.

I’m walking empty lanes

at the still point of the day,

past abandoned gardens

where magnolias flame unnoticed.

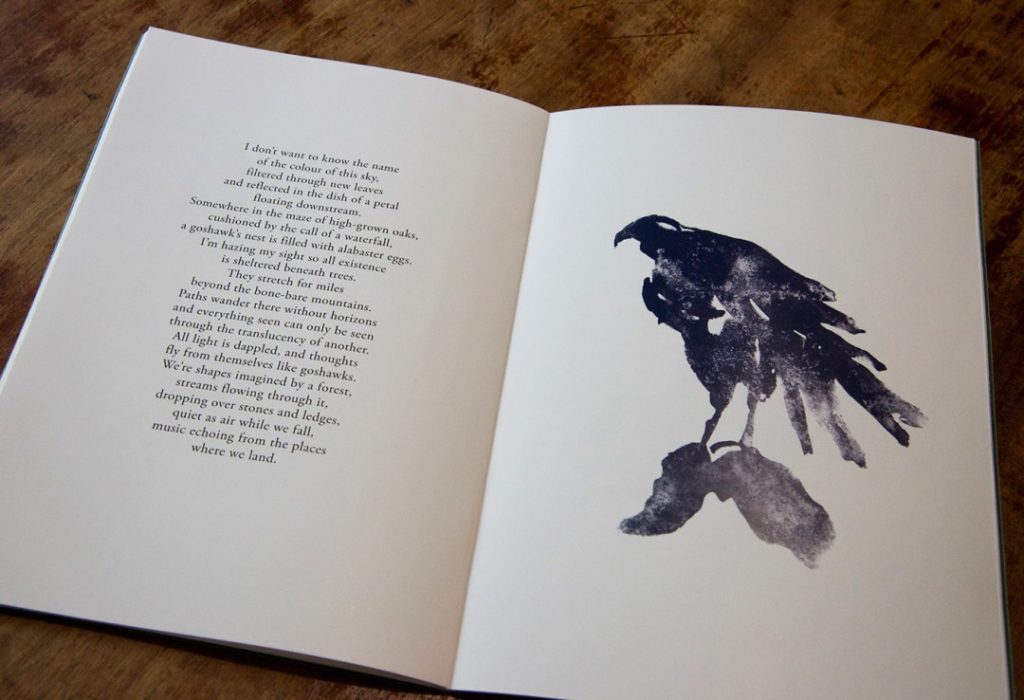

Written during the 12 weeks of the UK lockdown, this arresting new pamphlet by poet and artist James Roberts presents 12 birds in flight. From the Kingfisher to the Rook, through Lapwing, Heron, Sparrow, Swallow and Golden plover, the poems spring from a place of deep contemplation. Already a characteristic of Roberts’ writing, the lines are haunting, and perfectly poised, each carefully weighed to observe an innate sense of nostalgia and long-lost kinship. As the poems unfold they embody moments of grief and longing; the birds are addressed with a powerful, melancholy lyricism: ‘How many times have I missed you / as you fall like a dropped bead into glaze / because some track inside has led me / to a place where there are no birds?’ (– Kingfisher). As Roberts brings each bird into sharp focus, he distills their aliveness with his vivid, sometimes shamanic imagery: ‘I want to go hunting with the white owl, / ghost translucent against the dark, / to lean out from a high branch and dive / into the cracks of the underworld.’ ( – Barn Owl). He enhances the ghostly atmosphere with stark blue-black illustrations made with ink and salt soaking into thick, absorbent paper. Each one appears to embody the flight of the bird but where the salt has resisted the ink, the texture is crystalline, giving the appearance of depth, like darkness through stained glass. The birds are shadows, distinct and yet monochrome, as if printed on the back of the retina. In this way Roberts converses with the birds’ presence and their absence, and his encounters scrutinise our relationship with them.

I read the whole of this collection slowly, over several days, bird by bird, just as we collectively emerged from our enforced lockdown. The poems pinpoint the fact that it is perhaps not our presence but our gaze that the birds resist, and so reading them was not a panacea, but a reaching into image and myth, presenting one person’s mazy bird-map through that devilish time of isolation and quiet. Reading the poems, everything is slowed and distilled to its purest elements: bird, home, hill, tree.

All over the land this Spring people turned to poetry, as if somehow this form could untangle the complicated muddle of emotions we were experiencing. Perhaps it was because in these secular times poetry is the closest form to prayer. These poems seem to utter a heart-song for all of us, birds and people. Page by page, they stop you in your tracks, as the best poems can. Their movements resonate like the sound of a finger around the rim of a glass. Reading them, you move forward and loop back, awakening to a sense of deepened awareness. We long for kinship with our avian neighbours, but they do not need us, indeed they stare right through us, as the owl: ‘stared through me as it rose, / knowing that I wasn’t there’ […]

The dark and the rain reached out

and took it back to where it belonged,

that hole in the night which keeps watch

and waits endlessly for us to wake.

There is a sense in which these lockdown poems work in multiple landscapes: the physical, mythical, spiritual and emotional. In his prophetic book A Time for New Dreams (2011) Ben Okri says: ‘Heaven knows we need poetry now more than ever. We need the awkward truth of poetry. We need its indirect insistence on the magic of listening. In a world of contending guns, the argument of bombs, and the madness of believing that only our side, our politics, our religion is right, a world fatally inclined towards war – we need the voice that speaks to the highest in us.’ These poems do that. Their melancholy is underwritten with a strange kind of joy. They navigate naturally through the blur of boundaries between human and bird, deploying what John Burnside called ‘lit moments’ where the poet converses with the bird. Here, the poet speaks with the Kingfisher: ‘Because we humans, you see / little dripping dagger, are as restless / as water, and as inhabited.’ And here he strains to listen to the sound of the Curlew’s ‘long-lost call’ that ‘winter honed their notes / with only wind and sand as tools / the tone and tremolo it found / that could peel the skin from me.’

Here the birds’ world is as precarious as our own, where ecologies are joined, the human scale is expanded to the non-human and becomes planetary: ‘a siren flows like flood water / exploding from a breached dam’. Along with the birds difficult lives, our domestic life becomes uneasy as ‘this home we made is tilting into the melt’.

Reading that Roberts is gradually losing his own hearing adds a poignant layer of understanding to the sense of loss and longing that imbues each poem. The lyric intensity remained with me long after reading them: a sky reflected in the dish of a petal floating downstream; a heron teaching patience to stones; the crest of a lapwing as an antennae searching for an audible sign that ‘it is safe, at last, to be a lapwing.’ Resonating with the intense feeling and insight amongst these pages I saw them as an opened Pandora’s box. The birds that fly out of these pages wreak visions of our own folly, with both a haunting nostalgia and an unstoppable yet beautiful energy.

*

WINGED was published in June 2020 through James’s own Night River Wood imprint, and is available to buy here, priced £6.50.

Miriam Darlington has been obsessively tracking and writing about wildlife ever since she was small. She is the author of titles including Otter Country and Owl Sense, and you can follow her on Twitter here.