Christina Riley tracks down the work of pioneering seaweed collector and artist Mary A. Robinson.

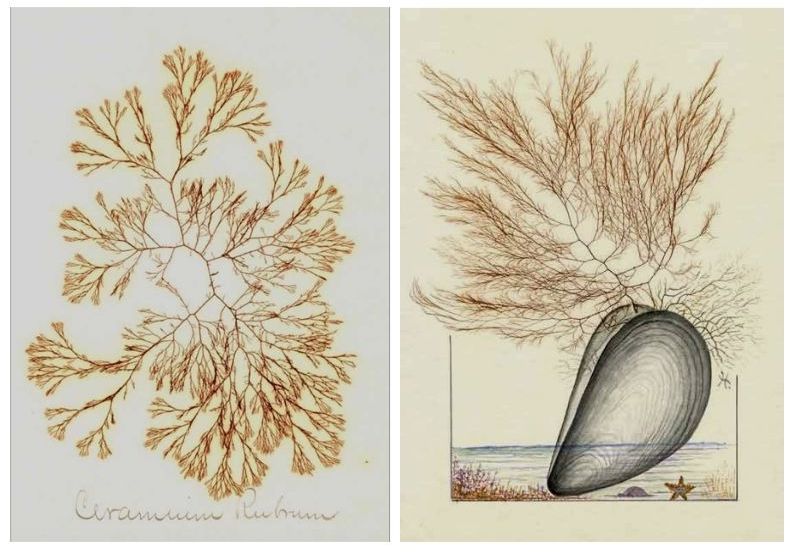

Ceramium rubrum; Illustration of unlabeled specimen emerging from a muscle shell, Mary A. Robinson seaweed album, Courtesy of the Archives of the Farlow Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard University.

On an otherwise empty beach, a mussel shell floats inches above the sand, standing on end with its slender tip pointed down like a toe into water.

It’s big. Bigger than any mussel I’ve seen before. It’s much bigger than a lobster. It must be at least ten times the size of the starfish which spreads its arms blissfully in its shade, stretched out in every direction like a piece of cosmos fallen from the sky and into the soft coastal plants, all pink and gold and windswept.

The mussel is almost black and, with concentric circles spiralling inwards, hangs in the air like a portal to an underwater realm. Its shell is translucent and through it the distant horizon of endless ocean cuts straight across its centre.

Cracked open ever so slightly, tiny tendrils of rusty orange seaweed escape out from its core and cascade upwards like mermaid hair floating underwater, lifting high into a bright, creamy white sky — cloudless, as if the sun burned them all away.

The scene was painted by Mary A. Robinson in the late 1800s and over one hundred years later, it sits before me inside the air conditioned rooms of Harvard University Herbaria. One year ago I wouldn’t have seen myself scuffling across these prestigious grounds alongside students with heads held high and HARVARD emblazoned across their hearts. I walked unassuredly with my head in Google Maps, waiting for a headmaster to pick me up by the scruff of my neck, sniffing out the barely-passed Photography HND. But as it happened, one night earlier that year I found myself sitting on my hardwood tenement floor in Glasgow deep in the throes of a new obsession—seaweed—becoming oblivious to the clock as it rolled past midnight and into the morning hours while I bookmarked page after page after page on nineteenth century botanists, seaweed collectors and artists.

Now I had an appointment at Harvard University Herbaria where, meticulously pressed between archival paper, filed carefully into ordered shelves and tucked away into darkened rooms, lay hundreds of pieces of seaweed lifted from the edges of the Atlantic ocean over 100 years ago by the hands of one of these artists — Mary A. Robinson.

Very little is known about Robinson and much of what I could find that night was a collection of assumptions and half-formed theories, left to dry over time like the seaweed. One of the guesses is that Robinson collected her marine specimens on the northeast coast of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, though this is not where she was known to have lived. It is known that her seaweed scrapbook came to rest in the attic of a house in Lambert’s Cove on the northwest coast, where it was found over fifty years after her death, yet it is unknown quite how it got there. And, perhaps stranger than her abundant surrealist scenes themselves, is the fact that her obituary contains no mention at all of art or botany.

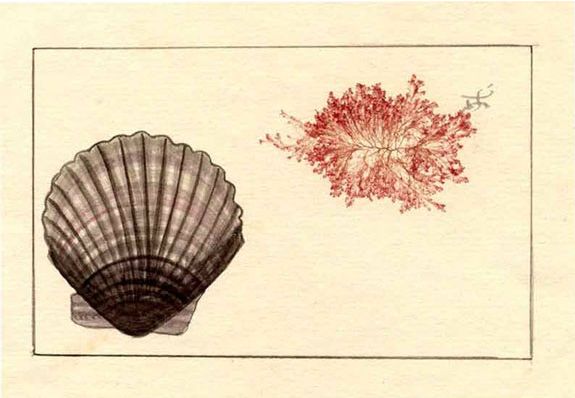

Illustration of unlabeled specimens with small scallop shell, Mary A. Robinson seaweed album, Courtesy of the Archives of the Farlow Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard University.

As is the case with so many women of her time, the curiosity that enshrouds Mary A. Robinson only thickens like sea fog with every dead end reached; the stories of women not so much lost at sea as never recorded as being out there in the first place. What we do know is that she left behind an extraordinary collection of vibrant and imaginative paintings as well as meticulously labelled algae specimens, tangling science and art to fill page after page of dreamlike ocean scenes.

Once on the far side of the Atlantic to view Robinson’s scrapbook with my own eyes, proximity to its pages only increases the distance between them and me. I realise just how little I know of her and of the world she collected from the shallows. When asked to identify which pages I wish to see (there are simply too many to pull them all), I hold the numbered list of specimens and can only stare blankly.

Rhodomenia palmata. Dasya elegans. Ceramium rubrum.

With no other option I choose blindly, as if reaching my hand underwater and grabbing at sand.

One by one the helpful Harvard archivists slide Robinson’s pressings from their folders until her delectably curious imagination fills my vision; seaweed specimens float off the aged yellow pages like ghosts, dripping brine onto the carpeted floor. Staring at each new page as it emerges, I catch an undeniable glimpse of a mussel shell. I knew I had seen it before, glowing from a laptop screen in the middle of the night, but here it was entirely new, just as a photo of the sea will never look or feel as good as standing at the edge of it. Looking closely — very, eyebrows bristling against the table closely — revealed that the seaweed blooming out of the shell is not, like the mussel, drawn on the page, but pressed directly onto it, picked out of the sea to be displayed as the centrepiece of this watery scene that poured from Robinson’s mind. I stare at it in silence, and in stillness, as if the slightest movement would break its salty spell.

‘So much depends, then, upon distance’, wrote Virginia Woolf in To The Lighthouse. Sometimes it is closeness that’s more difficult to grasp. So close and yet forbidden to touch, I leaned over them all with my hands clasped tightly behind my back, breath held as if it would shatter them. Though mere inches away from the very seaweed Robinson’s hands pressed onto this paper, I felt the full width of the Atlantic ocean swell between us.

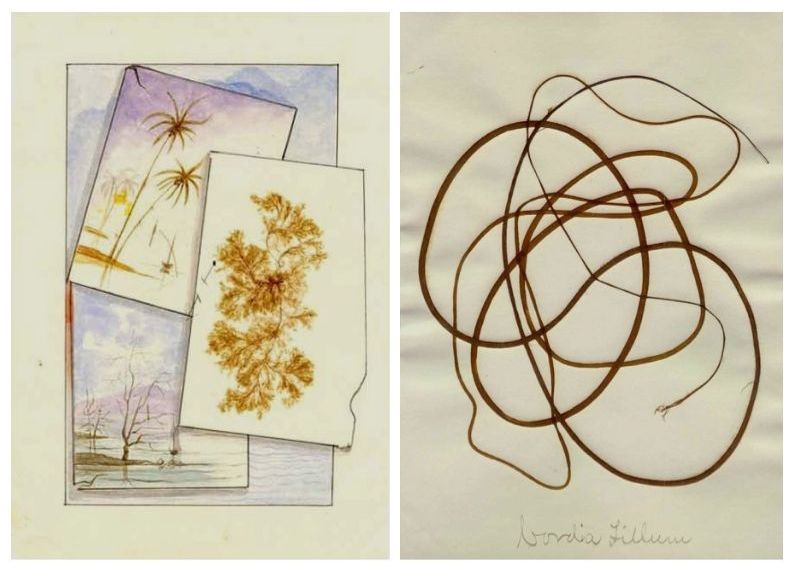

Illustration of seaweed along with palm trees and shoreline; Cordia fillum [Chorda filum], Mary A. Robinson seaweed album, Courtesy of the Archives of the Farlow Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard University.

I don’t know who Mary A. Robinson was, but I imagine her kneeling on the shoreline at low tide, eyelashes sticking together with salt spray and long hair tied back in what were once neat, traditional Victorian twirls pinned to the side of her head, unravelling with every gust of sea breeze. Dressed inconveniently in long and billowing skirts that would trail heavily through salt and sand, they’d be hiked up when something beneath the shallows caught her eye. The skin of exposed knees would slowly become imprinted with the patterns of shells and barnacles.

I wonder what drew her attention to the pieces she collected — was it by species, or rather colour and shape? Their hypnotic fluidity underwater? What called her to the edge of the sea? Was it the same pull that lures me there one century on? The ocean holds more questions than a single lifetime can answer, each one branching off into a dozen more like tiny tendrils of dulse and tangle. Every inch of sea fog cleared reveals something new in the distance, barely visible but just close enough to reach for.

*

You can view Mary A. Robinson’s digitised seaweed album here.

Christina Riley is an artist and writer based on Scotland’s west coast, drawing acute attention to the details of the natural world with a particular focus on the sea. In 2019 she was longlisted for the Nan Shepherd Prize for Nature Writing and later that year started The Nature Library, a travelling library and reading space. Her work has recently appeared in The Clearing, Elsewhere Journal and Gold Flake Paint, and her photographic series The Beach Today will be published by Guillemot Press in 2021.

Visit her website here. You can also follow Christina on Twitter and Instagram.