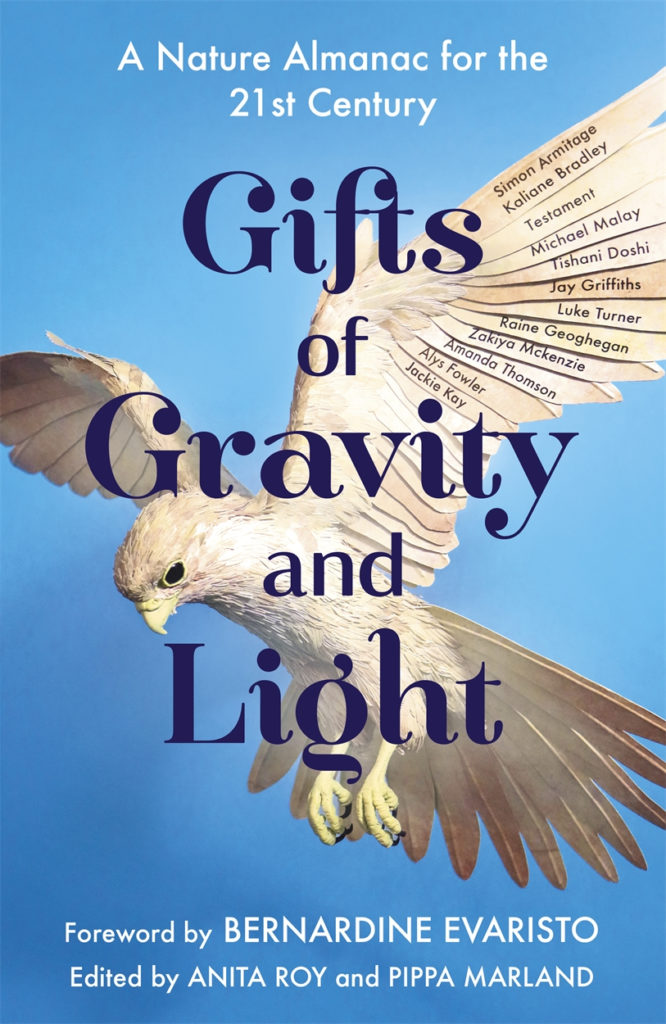

Edited by Anita Roy and Pippa Marland, and with a foreword by Bernadine Evaristo, ‘Gifts of Gravity and Light: A Nature Almanac for the 21st Century’ is just-published by Hodder & Stoughton. Read an extract from Michael Malay’s contribution, titled ‘Severn Beach’, below.

Eels are tiny when they are born, no bigger than a grain of rice, and completely transparent. If you looked at them closely, you would see into the world. But as they grow older they begin to absorb light, to bend and to capture it. Their skins darken, their bodies lengthen, and their translucency is replaced by a murky brown. Streaks of yellow run down their flanks, like bars of muddy gold, and their eyes grow more pronounced. The grain of rice has become a yellow eel. But the transformations only continue, change following change. As they grow older, their yellow flanks darken, shade into umber, until, reaching full maturity, they take on the colours of a starry midnight. A slick, glossy black covers their top half, while their underbellies take on a silvery sheen. Glints of brown and green cover their back like flecks of mica.The yellow eel has become a silver eel.

European eels are born in the Sargasso Sea, where they emerge from unknown depths – unknown because, despite many attempts, no one has ever seen them mate in the wild. Rising as eggs on the water column, they tumble out of tiny yolk sacs, and during these first months they do not look like eels so much as willow leaves, with their flared-out bodies tapering to a fine point. (Newborn eels are known as leptocephali, meaning ‘slim head’.) At first, these willow leaves are unable to swim, and so they float on the great ocean roads of the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Drift. These are the same currents that carried their ancestors east and that allow them to travel extraordinary distances: eels entering the coastal waters of Ireland and Britain will have travelled four thousand miles, while those that travel to Latvia, Estonia and Iceland will have gone even further, some as far as five thousand miles.

Later in life, some of these eels will continue travelling, happy to drift like houseboats. Most, however, will become faithful to a particular place. After reaching home ground – it could be an estuary, river, stream, lake, pond or ditch – they will create little burrows in the earth, by clearing away mud with their powerful snouts. And they will stay there for years, resting in the daytime and hunting at night.

And then, many years later, the long journey home . . . On autumn nights, when the moon is in its last quarter, and after rain has swollen the rivers, adult eels will quietly leave their mud-holes, turn their noses west, and swim for the Sargasso. It’s a place they hardly know, having left it when they were only one or two weeks old, yet it’s a seascape written into their bodies, and to which they return with fateful precision. Beginning its life as a wayfarer, the eel ends its life as one too, and perhaps it always knew this moment would come: this quiet sea-journey, this long swim home.

What might that be like, to feel the call of home from four thousand miles away? Is it a hunger? An ache? Or something stronger?

*

‘Gifts of Gravity and Light’ is out now and available here (£16.99).