Róisín Á Costello tracks the corncrake through story and history, mud and ink.

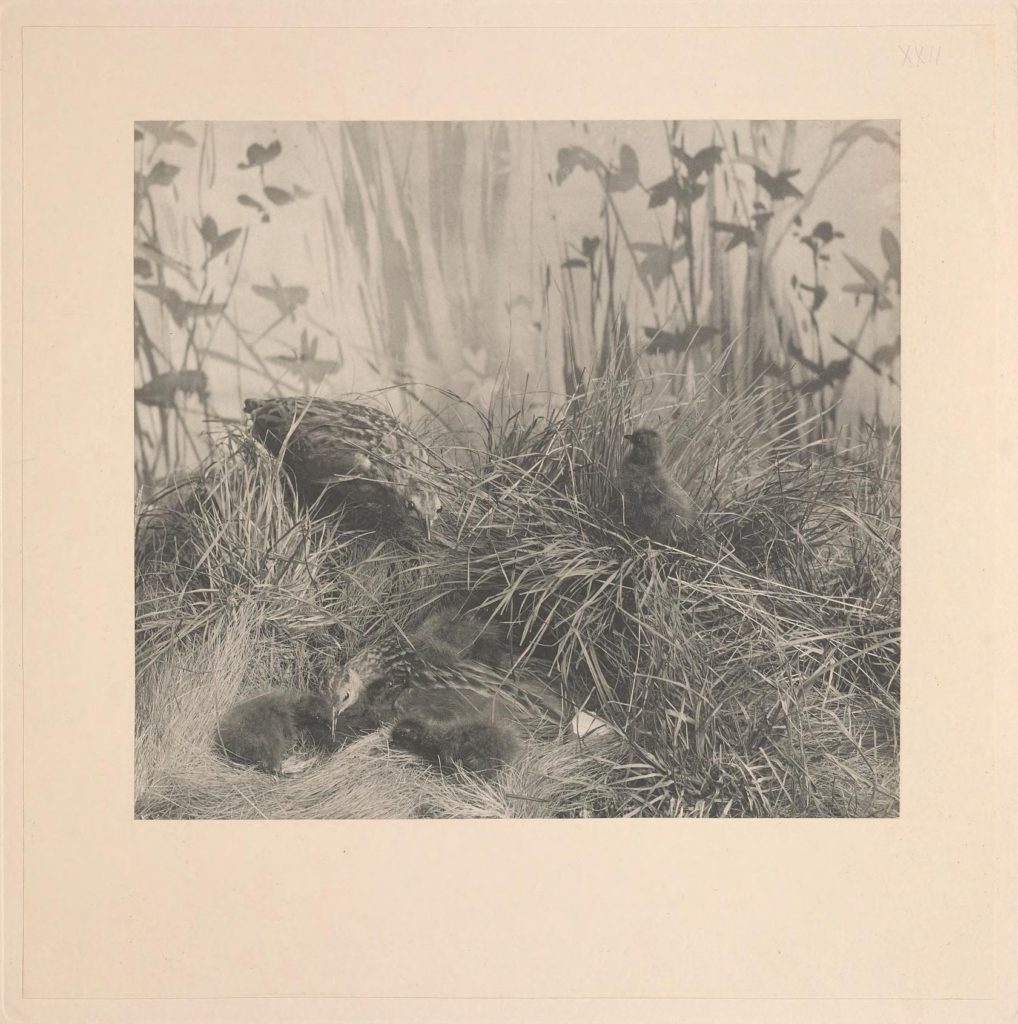

Image taken from ‘Groups of Birds: Twenty-five photographs (printed in platinotype)’, Grosvenor Museum, 1895, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

I feel as if I am underwater. The tops of the mountains have been obscured by cloud all week and even though it’s midday, and well into May, it has the feeling of dusk. This first kilometer of the valley is always darker anyway, overshadowed by the close, vertical walls of the surrounding mountains. On a wet day like this, the limestone of their flanks is a slick pewter, and even when I reach the open floor of the valley the skies seem to press down — rain-darkened and swollen. The weather blunts everything, blurring the edges of the landscape, and making even nearby sounds seem far away — a kind of dull silence that reminds me of the poem by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill ‘Níor cheol éan, níorbh labhair damh, níor bhéic tonn, níor lig rón sceamh.’ No bird sang, no stag spoke, no seal roared, no wave broke. I am walking to retrieve a hazel rod I passed a week ago. I have decided it will make a nice walking stick. I have developed an unfortunate habit of crossing paths with the feral goats that roam around these mountains and I don’t fancy my chances against one of the pucks without a good stick. Not that I fancy them much with one either.

And then I hear it, just twice, barked into the damp air. A sharp, metallic sound. Out of place in nature. I stop, listening for another call, the thick grass that borders the road licking coldly at my ankles. Until this moment, I would have denied I was listening for this sound at all. But as it grates out again, I remember my grandfather trying to imitate it and I know that, really, I have always been walking in expectation of hearing it in this valley again. Even though I’ve heard it only once before — as a child, pressing down on a domed button in an interpretative center in Donegal. I remember thinking that the button was broken. The same mechanical, grating sound had cracked through the room. Like the false start of an old engine on a cold morning, or the crunch of metal on metal as the gearstick does not quite make it home. The call of a male corncrake. In videos the corncrake’s beak snaps open and shut, whiplashing the bird’s head back like a Pez dispenser as it calls. Crex crex, the bird’s Latin name, from the ancient Greek ‘κρεξ’, is onomatopoeic — an attempt to reduce the sound to paper. One writer says it is like ‘a comb being scratched along the edge of a matchbox.’ The description doesn’t do it justice. And it can’t describe the pure volume of it. A male corncrake in full voice can be heard for nearly a mile.

In the national folklore archives in Dublin, interviews from the 1930s list the corncrake as one of the most common birds in the country — reports from nearly every parish list the bird. In fact, they were so common throughout Ireland and Britain during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that crofters on Uist in the Outer Hebrides complained that the sound of the birds kept them awake all night during the summer. They weren’t making it up. Early in the breeding season, a single male corncrake can call more than 20,000 times in a single night, reaching a feverish pitch between midnight and 3 am. It makes the Irish saying, ‘codladh an traonach chugat‘ (the sleep of the corncrake to you) seem a bit sly. How many corncrakes there must have been for their scratching chorus to be loud enough to drown out the chance of sleep. I think of the writer Amy Liptrot, nearly a century later, driving the midnight roads of Orkney trying to catch the sound of a single bird for conservation records and I wonder why this corncrake is calling during the day in our valley. Perhaps the dark swell of the rain-sodden sky has fooled us both.

By the time the children who recorded the interviews for the folklore archive in the 1930s had children of their own, the corncrake population in Ireland had plummeted. There are few estimates of how many corncrakes could be found in the country in the 1930s, but by 1978 it was estimated only 1500 birds were migrating to the country each year. Not enough for them to be a common bird in every parish. Not even enough for one pair in every parish. The decline was not uniquely Irish. Scientists working in Eastern Europe and Russia began to notice similar patterns, while in England, even by the 1930s the corncrake population had contracted sharply, the bird’s range receding to the Western and Northern edges of the country. But in Ireland and Scotland, the corncrake held on long enough that their decline was recorded with increasing concern as the twentieth century wore on. The pattern of the retreat — into the valleys of Wales, the Scottish Highlands, West to the Atlantic fringes of Ireland — maps almost precisely onto the expansion of mechanised farming outwards from Southeastern England at the end of the nineteenth century. As hedgerows and scrublands were reclaimed and made ‘productive’ the tangled wastelands of marsh, nettle, and cow parsley the corncrake needed for nesting became rarer. The corncrake found itself pushed to the margins, to the ‘unproductive’ spaces not worth taming. With so little habitat, the corncrake began to nest in corn and wheat fields, only to have its eggs or chicks mown down as the crop was cut halfway through their breeding season. As the bird’s number declined, farmers were given subsidies to cut their fields from the center outwards — giving the birds time to flee to the edges, away from the machines. It didn’t work. In the summer of 1996 when I pressed the button in Donegal there were less than 600 breeding pairs of corncrakes recorded in Western Europe. I listened for twenty-eight years before I heard the call again. The summer I hear it again, in 2021, Ireland’s national biodiversity audits estimate that a quarter of the island’s bird populations are at levels that require conservation intervention. Roughly 25% are considered endangered. The corncrake is one of those most at risk but even birds whose presence we have taken for granted are going quiet. Between 1980 and 2020 researchers estimate that across Europe there are 75 million fewer starlings, 247 million fewer house sparrows, 68 million fewer skylarks.

The overwhelming majority of the corncrakes that can still be heard in Ireland are recorded in spots like this valley. Fingernail-thin slivers of land along the Western coast of Ireland. From Donegal, along the fringes of Mayo and Galway. Areas that have developed a strange kinship with this bird. In the national folklore archive, one interviewee, asked about the corncrake, says that the bird’s singing gladdens Irish people’s hearts because it reminds us of our own language, reminds us that birds too have their own languages, their own ways for expressing joy or sorrow. I wonder if it is a coincidence that the corncrake holds on in the areas where the Irish language does. The small areas where it is still found are, overwhelmingly, Gaeltachts — areas where Irish, and not English, remains the first language of the population and the one used on a daily basis. Areas land is generally poor, where farms have been small, where land is often hard to cultivate, ‘unproductive’. In these spaces both bird and language have endured. Both fugitives in the long grass, holding out against the forces that would cut them off. The places where the corncrake is still heard in Ireland are the same places where old harvest times were kept longest, where small farms still include tangled fields of cow parsley and nettles, and where the Irish language’s way of describing nature has leaked into our way of handling her.

The Irish-speaking population of this valley began to decline almost in parallel with the corncrake. Decimated by famine in the 1850s, its remaining speakers trickling away over the next century as migration and modernisation took their toll. The language came to be viewed as old-fashioned, backward. It had no value in international markets, it offered no direct benefit in business or trade to those who spoke it. Generations stopped passing the language on until finally, the area around this valley was declared officially English-speaking in the 1950s. Like corncrakes, it is hard to say how many people are left who speak Irish fluently. Whose language has the authenticity of birdcall, learned as a hatchling. Certainly, mine doesn’t. My Irish was learned in the captive spaces of school. And yet. And yet here we both are, beo ar éigean. Alive. Searching for each other through the haze of rain in a valley where statistically, neither of us exist. Where our voices should not be heard. I stay, listening for another call until the approaching rumble of a car breaks the silence.

Days later, I am walking through the valley again when my dog stops at a bend in the river. He freezes, some instinct pulling him towards a spot across the water. I follow his gaze just in time to see a bird with long legs rush through a gap in the drystone wall and into the safety of the tall grass beyond. I do not hear the call again and I wonder if I ever will. We have already lost so many of the birds that once flew through this landscape. Carraig an Iolair, Eagle’s Rock, a soaring crag overlooking a deep meadow six kilometers from here carries in its name an echo of the time when the mythical stories of Fionn Mac Cumhaill claimed that the country echoed with the sound of the eagle ‘screaming on the edge of the wood,’ and the corncrake ‘clacked — a strenuous bard.’ The rock has been quiet for as long as anyone can remember, its name the only clue to a time when this landscape was richer than we can understand.

The earliest Irish poems describe landscapes alive with birdsong, noisy with the calls of stags and the howls of wolves. Even when the poets turned their attention to the actions of kings and warriors nature was not merely a setting for their stories, but the strongest force in them. Even the smallest creatures in these accounts possess a precious quality. The goldfinch is lasair choille, the flame of the forest — a lick of bright gold darting among the trees. The chaffinch as rí rua, the red king, for his blushing chest feathers. Irish mythology says that the lon dubh, the blackbird, is one of the three oldest animals in the world. The wingbeats of these birds stitch together the settings of the ceantar (the world of humans) and alltar (the world of spirits). The house of the fairy woman Crédhe is thatched with the wings of crimson, blue, and gold birds. The palace of Manannán, the Irish sea god, is thatched with the wings of white birds — wings that act as a haunting foreshadowing of the fate of his own grandchildren, who are cursed to live as swans for nine hundred years. The battle goddesses of Irish legend, the Mór-Ríoghain, are themselves both one and many, woman and winged, turning, at will, from woman to carrion crow, from maiden to cailleach or crone, and from one being to three, Badb, Macha, and Nemain. Flock, fledgling, bird, spirit, woman, God.

The power of birds imbued those who told their stories too. Cormac’s Glossary and Tochmarc Emire (The Wooing of Emer) record that the cloaks of the chief poets of Ireland were stitched from the feathers of birds. I imagine the chief poet of Ulster, sitting by the King, his shoulders hunched against the cold, eyes narrowed against the smoke of a dying fire, and I think there is something more than the feathered backs of these two tribes that unites them. These scéalaithe were keepers of an oral tradition, a history of place and people passed mouth to mouth, images that lingered for a moment and then faded with the wood smoke, curling into nothing. Like a sparrow’s breath disappearing on the cold morning air. I imagine the ruffled cloak, and the union it represented — of those creatures who could move between worlds seen, and those only imagined.

I find myself tracking the corncrake — through story and history. Calling up tattered manuscripts and ignored memoirs from the bowels of the University Library. Pawing through boxes of family recordings and pictures. Mapping flight paths. In the National Library in Dublin, two metres separate each occupied desk. My mask is making my reading glasses fog, the press of cotton against my nose flushing warm breath up to condense thickly on the lenses. The alcohol burn of disinfectant is still drying on my hands as I slip into my assigned seat. Measures to ensure our survival. A door hidden in the wood-paneled wall has been propped open to allow air to circulate, and a breeze carries the sound of gulls from the river into the chilly space. I am tracking the corncrake through mud to ink. She is as elusive as ever. The ‘hoarse and noisy’ birds that Gerald of Wales wrote were ‘innumerable’ when he visited Ireland in the twelfth century are strangely absent from what has leaked through the written record. And yet. Now and then she flashes into view. The Triads of Ireland, a miscellaneous collection of linked triptychs on subjects from law to geography, names ‘the nettle, the elderberry, and the corncrake’ as the three signs of a cursed site. Like the vanished eagle of my valley, she sometimes appears in the contours of the hills themselves. On the wafery paper of an ordnance survey map, I trace the Anglicised bowdlerisation of her. Reduced by English soldier surveyors in the nineteenth century to a strange phonetic garble, she echoes off the lines of Carntreena (Carn Traonach — Cairn of the Corncrake) and Largatreany (Learga an Traonaigh – Slope of the Corncrake).

The picture of the corncrake which emerges in the scraps I find is contradictory. Authors write that her eggs are red, or blue, brown, or speckled. She lays four, or eleven, or eight of them. She is brown, or maybe grey or nearly black. She is a foolish bird because she lays her eggs on the ground, or she is smart because she makes not one nest but three — two decoys, and the one where she keeps her chicks. It seems that even after centuries the corncrake remains a creature that belongs more to the uncertain world of the alltar. She is always reflecting our imaginations back at us. In both Ireland and Scotland, until the beginning of the twentieth century, it is widely believed that the corncrake makes its distinctive call not by opening its beak, like other birds, but by lying on its back and rubbing its legs together. In a turn for the weird, the belief (apparently held in earnest) is that the corncrake does this because it believes its legs are keeping the sky from crashing down onto the earth, and that she sings a song as she goes about her lifting,

‘Tréan le tréun, Strength to the corncrake,

tréan le tréun, strength to the corncrake,

dhá gháigín an éin, the two little legs of the bird,

A’ ciméad an aeir go léir, Keeping up all the air,

Uaidh suas, Uaidh suas! Up with them, up with them!

Something almost prophetic lingers at the edges of the story. It was the corncrake’s decline that signaled what was lost as we came to value ‘productive land,’ defined by maximised yields and profits. Its fading call was one of the first signs of a degradation we are now struggling to reverse. The sky might fall – not because the corncrake is no longer present to hold it up, but because the landscapes we created, and which displaced this bird, are more barren than they appear. We are learning too late that the value of things that cannot be calculated on a balance sheet is not zero. It is something closer to infinite. I think this is, perhaps, the realisation that is driving the revival of the Irish language now — a sudden recognition that this language, backward and traditional and not-useful, held in its ways of thinking about our world and our place within it insights that cannot be stored elsewhere.

At the end of my day searching for the corncrake I cycle home across the city. I pass a house whose roofline is crenellated with pigeons; their squat backs picked out by the fading sun. It is a strange thing to feel such kinship with a bird you have never seen. And then I remember — I have seen a corncrake before. I change my course and pedal a little harder to reach the Natural History Museum before it shuts. When I arrive, there are 30 minutes before closing time. I stride up and down the rows of birds in their glass cases — nestled in felted grasslands, or clambering along varnished wooden logs. I must have walked past the corncrake family a hundred times as a child — eager to get to something more exciting. But here they are. I stand and look at them — frozen in a dust-filled ray of sunlight from the tall windows. The female crouches a little, one glassy eye turned towards me, her comically long-toed foot hinting toward a step, making as if to move between me and her chick — a ball of downy, black feathers. The male’s head is angled up towards the whale skeleton that swims through the air above them, towards where the sky should be. The faded labels on the plinths that hold them read only ‘Corn Crake, Crex crex, Dublin.’ It does not give their Irish name – ‘an traonach’ or ‘an gearra-ghuirt,’ — the bird who sleeps all day and calls all night, the corn dweller who comes in the first four weeks of March. Eagles and turtledoves and cranes sit, frozen, around us. All the silences of our landscape press down on one space.

*

Róisín Á Costello is a bilingual writer and academic who lives and works between Dublin and County Clare, Ireland. Her writing has been published in Elsewhere and The Hopper, and is forthcoming in the Spring 2022 issue of Banshee. Róisín has previously been shortlisted for the Bodley Head/ Financial Times essay competition and in 2021 was selected as the recipient of a Words Ireland mentorship by Dublin City Council.