By light of a thin moon, Richard Fleming lies in wait for silver eels.

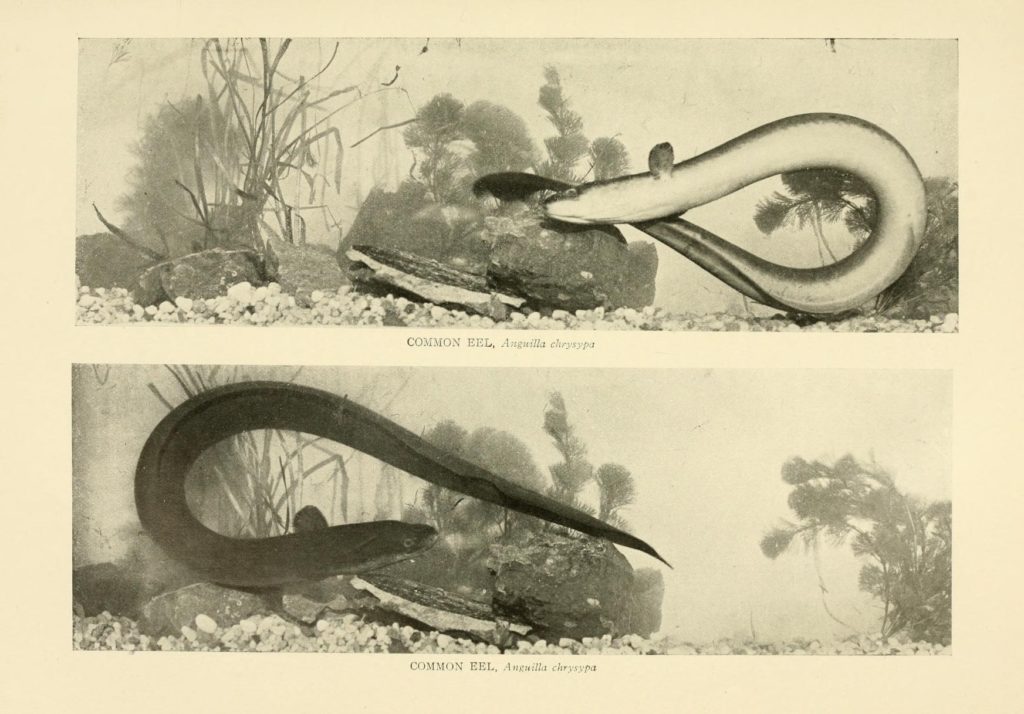

From American food and game fishes: New York: Doubleday, Page & Co.,1902, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

It is the first night of the first of the darknesses of the eels and the moon is thin, rising behind the alder trees along the river. I light the oil lamp and pump it into brightness as the vapour hisses into the wick. When it is dark I feel as helpless as a swift lying on the road. My element is light, and all I have of it is the circle cast by the oil lamp. The shadows of thistles and of clumps of rushes radiate from the lamp as I walk the field in my yellow trawlerman’s oilskins with long-handled net and rake over my shoulder. The shadows circle round the lamp until they point and fade into the fear and the darkness behind me, and the shadows of my legs as I walk are scissors chopping the darkness.

Every hair on my neck is ready for anything sudden or surprising. I know there is nothing here more dangerous than me, or maybe a bull chewing the cud with the cows lying among the thorn brakes, but I am as tense as if there were tigers in the darkness. Sometimes eyes glow in the lamplight.

The field slopes down under the hazels at the edge of the wood and the track crosses old leats, damp relics of all the traps that have been built here to hold back the river and filter out the silver eels, all the traps that have burst their banks when the trapper wasn’t watching, and been rebuilt as the shape of the river shifted. There are fences here that rip the oilskins if I am not careful, and then I’m in the wood and the ground is drier, a litter of leaves and rotten sticks, and over the little bridge to the eel trap.

I am in two spheres now, one of light and one of sound. The water running under the sluice, and through the grids of the eel trap, makes a dome of sounds, watery sounds, trickling, gurgling, rushing and bubbling as the water drops over the ledge into the brick box with the steel lid where the eels land. These sounds cut off any other noises, except above the centre of the sphere where the wind is shaking the trees. There is a silence in the midst of sound, a tinnitus of water and a circle of light in the darkness. It’s a wild night. It has to be. It’s the first darkness of the autumn, the first night when eels might run, down this river flowing off the Beacons, through an ancient glacier-lake and into the river that the beavers used to dam, in its strip of wet alder woodland.

The weir is choked with leaves from the alders, leaves that float and turn in the river, and the water is dangerously near to overtopping it. I sit on the concrete walkway above each sluice gate in turn, dragging my rake up the rods, shaking the leaves off into the pool below and behind me. The water level above the weir starts to drop as I clear all four grids, but the river is still coming down hard and the pressure is sending a strong current under the sluice that runs into the next chamber of the trap, brick walled, coffin shaped, with more grids to let the water drop into the deep channel below and beyond. I have to clear all these grids to keep the water levels down, sitting on the concrete with a rake that ought to have a special name.

For a while now I can sit and wait in my circles of sensation and of deprivation, in the rain and wind and cold, sitting on the wet concrete with my storm lantern. I hold my hands in the heat above it, and enter a kind of trance, listening to the water sounds, listening for eels and alert to every sound. Sometimes a salmon startles me, splashing just behind me in the darkness. I have to sit here keeping the weirs clear every night of every darkness. If the leaves block the grids and they overflow, the eels may run over the weirs without my knowing, and if I don’t know that the run is still to come I cannot sit here in the rain for fourteen nights each lunar cycle waiting for eels that have passed by on down and out to sea. On the their way to the Sargasso for the climax of their lives, writhing panmixia, sex with each other, with themselves, with the very ocean depths, mixing all the eggs and sperm of their generation to fuse into another generation to slide transparent up all the rivers of Europe.

These are the silver eels. They have migrated here from across the Atlantic as organisms almost microscopic among the plankton, coming from the Sargasso Sea where they were hatched. In the plankton they are food for anything that has evolved to be able to sieve them out of the water. They may have fed whales or basking sharks as they floated with the Gulf Stream towards Europe, changing into transparent elvers, glass eels, as they sensed the vibrations of the ocean crashing on our western shores beneath the changing moons that rule their lives. They will have used the huge tides that sweep them into the Severn Estuary, and cannily moved to the very sides of the Severn as the tide turns and the river runs out. At the edges of the river there is a backwash which helps them swim upstream past the ‘tumps’ of the elver fishermen, even now still allowed to catch them, and as they swim on up the river, growing into yellow or green fingerling eels, they will have fed ducks, and herons, and otters. They will have returned nutrients from the oceans to the river system, and boosted all the creatures finding food for their spring offspring, as they spread up the rivers and branch into the tributaries and the brooks and the ditches and the lakes. Their presence in every artery of the watershed, eating small crustaceans and passing their nutrients on to the otters and herons that eat them, will be part of the complexity of the ecosystems of these waters and the land around them, just as the returning salmon enter the rivers flowing through the forests of western Canada, are eaten by the bears, and thus fertilise the forests.

The waters flow down and the eels swim on up, until they are mature and need to go back to sea to breed. Then they turn from the muddy colours of the freshwater eels to the black and silver camouflage of sea fish, with a skin adapted to the osmotic pressure of sea water and huge eyes to see in the ocean depths, and they wait for the darkness and the autumn storms in the big lake that has been famous for centuries for its ‘eels and tenches’. And I wait in the wood and the rain for the few nights when they let the water wash them out of the lake and down the river. I wait wondering if they are lying in a mass where the river leaves the lake, waiting for a decision, or if one night they set off one by one and meet each other like trickles joining brooks and brooks joining rivers, their diffusion through the watershed reversing as they flood back to the ocean. Sometimes there’s a slithery break in one of the strains of sound I hear, a smooth break, maybe a plop, as a big eel drops into the trap, but mostly it is the regular ragged even sound of water running through that I hear night after night. I lift the lid above the chamber. There are two or three eels, a few small males, one or two big females. This is not the night of the big run.

For hours it is dark and it rains and then it stops and the river brings more leaves down. I wake from my torpid state and rake some leaves. I pump the lamp if it grows dim, and warm my hands above the hot lamp and doze as my hands sink closer and closer to the hot lamp, until I wake with a sizzle and get up to rake the grids some more and watch the bit of moon move over, the only sign that time is passing.

Then perhaps it isn’t quite so dark, and the trees become a daylight kind of grey and then it really isn’t quite so dark and the lights of a van go by on the top road and the night is over. I scoop up half a dozen eels from the trap with my long-handled net and drop them in the side chamber, the keep, with perforated bricks that let the water through, and a solid locked lid.

I walk back hungry over the innocent safe early morning field, where the cattle have breakfast spread before them. Wondering why I seek no comfort at the eel trap other than my oilskins and my oil lamp. No sandwiches, no coffee, no hip flask, in the dark with just enough light to work in. No shelter, no company except the ancient visceral fear of what may be crouching in the dark behind me and what may be lurching towards us from the future.

*

A note from the author: This piece describes a time many years ago when it seemed that the eels would run for ever and the salmon leap in the rivers year after year. I spent a lot of money every year buying trays of elvers from the elver merchants along the Severn, and giving them a free ride past many dangers to lakes where they could thrive, and I felt my conscience was almost as clear as I would have liked it to feel. And I knew that of all the silver eels that ran to the Sargasso only a tiny fraction would be caught. I had been out at night in the boat fishing for silver eels with Pieter the Dutchman, who worked a pair of trawl nets across the Severn when it was in full flood. I have never done anything so dangerous.

Those who calculated ‘sustainable levels’ of fishing in those days only attempted to calculate the fishing effort beyond which a population of fish would start to decline, and for them the eel was not significant enough even to do that. They were only interested in fish that were an important economic resource. They did not concern themselves with the role of a species in the whole ecosystem, or with the notion that the eel might be another ‘keystone species’. There was no attempt to regulate eel fishing apart from charging a very small fee for every ‘fishing instrument’, or to regulate the elver fishing and prevent the export of this keystone species to eel farms in the East.

Brexit has made export of elvers to Europe more difficult because of European regulations to protect the species, and export of elvers to the eel farms of the Far East is now illegal, but elver smuggling is, in terms of individual animals smuggled, the worst wildlife crime in the world.

I have lived in nature much of my life, as a forest worker, a fisherman, and a cider maker. Working as an eel fisherman was part of my ecological education. One of the results of a growing ecological awareness, in the words of the great Aldo Leopold, is that ‘one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is invisible to laymen’. The memoir from which this piece is taken juggles with the delight of working close to nature and the growing pain of living in that world of wounds.

*

Read Richard’s previous writings for Caught by the River here.