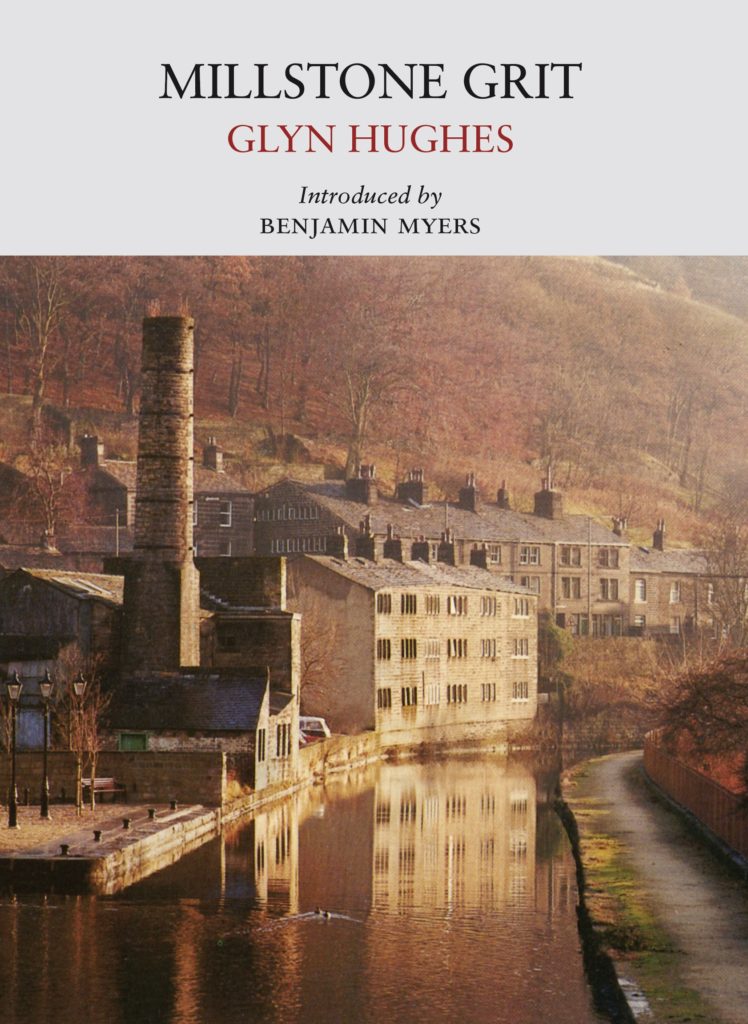

Read Benjamin Myers’ introduction to a new Little Toller edition of Glyn Hughes’ ‘Millstone Grit’ — an exploration of the moorlands alongside the industrial towns of the Pennines.

There are beasts buried deep beneath England.

Great beasts of glistening stone and ragged rock. Every now and again they show themselves, knuckling their way through the crust of the moor or fell – a snatch of spine here, a tip of a tail there. Their trick is never to be entirely dormant, nor to reveal their great mass at once. This has served them well for hundreds of centuries.

In the uplands of the Pennines, where East Lancashire shakes calloused hands with West Yorkshire, and the scars of industry litter the land by way of abandoned quarries, ruinous mills and obscure moss-covered dells and cloughs, the beasts are made of millstone grit.

Gritstone, as it is more widely known, is the bedrock of these haunted lands. It is coarse and from a distance appears dark grey in colour, yet it changes when wet, which is often, and sometimes is capable of sparkling in the sun as if it holds within it the crushed dust of the most coveted diamonds. Often it is described as being ‘spicy’ and when underestimated – by those climbers, for example, who attempt to scale the great sculptural formations across the region – it can turn round and hurt you. It can scrape off your skin. Put you in your place.

Stoic, solid, immovable, ancient: millstone grit is as perfect a symbol for the North of England – the old North – as one can imagine.

It is also the theme that runs through the centre of Glyn Hughes’s curious account, like words through a stick of Blackpool rock. Millstone Grit is a book that somehow manages to be simultaneously travelogue, memoir, guidebook, historical overview, poetry, proto-psychogeographical study and much more besides, yet without ever once standing still long enough to be truly categorisable as any of these. Like the best books, it exists in a genre of one. It is simply Millstone Grit.

I first came to this book when I moved to the region over a decade ago, attracted by the wide open spaces, the changing daily drama of the sky and a reputation for harbouring characters best described as unique. The small town of Hebden Bridge, which sits somewhere near the centre of Hughes’s perambulation, is world-renowned today for its population of hardy hillwalkers, hippies, lesbians (it has more gay women than anywhere else in Britain), writers, artists and activists. Beyond it, in amongst the ancient farming hamlets that dot the uplands that reach in all directions to link such towns as Todmorden, Haworth, Marsden, Ripponden – and beyond them, larger conurbations like Rochdale and Oldham, Halifax and Huddersfield – live those for whom town life is still a little too hectic.

Millstone Grit is a book about crossing imaginary borders – between these places, but also people, ideas and time itself. The author peels back the eras and peers at what lies beneath. The framework is a fifty-mile walk that Glyn Hughes, a teacher-turned-poet when he published the book in 1975 – but also later an award-winning novelist, dramatist, journalist, broadcaster and painter – took through the eastern edge of Lancashire and into the West Riding of Yorkshire, two counties with a longstanding rivalry that has been reduced to little more than jovial one-upmanship today.

Hughes was born in Altrincham, then in Cheshire, now Greater Manchester, in 1935, and came of age in the genteel landscape of North Cheshire, but took up residency in a derelict house that he purchased for £50 in 1971 in the rural village of Mill Bank, near Sowerby Bridge in Calderdale, West Yorkshire. Though less than forty miles from the place of his birth, the dramatic surroundings of the steep-sided valley feel a world away, and Mill Bank – then in sharp decline following the collapse of the cotton and wool industry – provided endless inspiration (and was designated a conservation area in 1976). The house had rotten floorboards and no electricity or running water when Hughes purchased it, but it did have a ‘coal ‘ole’ through which coal was shot straight from the street into the windowless kitchen, and had what an estate agent might describe as ‘bags of potential’. Others might simply have seen decay in keeping with the then-ailing area.

As Hughes conveys on his meandering journey, historically, this is dark territory, rebel territory, a place defined by rock and rain, and where the humour is as mordant as the gritstone is dark. Here old packhorse trails, ancient highways and the fast-flowing Lumb Beck continue to remind visitors and residents of the challenging landscape and rich history, while the place names alone are a form of poetry, with Mill Bank sitting close to the villages of Triangle, Kebroyd and Cottonstones.

Using only simple tools and cunning, it was in these valleys that the Cragg Vale Coiners staged a covert counterfeiting operation that derailed the national economy and rippled all the way to Whitehall. Here, too, the Luddites went on the rampage against the burgeoning mechanisation that was devaluing their skills.

The other Hughes – future poet laureate Ted – passed his first seven years in nearby Mytholmroyd, and revisited it continually in his work. In the cemetery at Heptonstall, high up on the hill above Hebden Bridge, and next to the stony skeletal remains of a burnt-out church, lies the body of his wife, the brilliant poet Sylvia Plath Hughes, dead at thirty by her own hand. Over the moors in Haworth meanwhile, the Brontë sisters created entire kingdoms.

There are darker echoes in this stretch of this Pennines, too, a place of several notorious modern murderers and bodies buried up on the cold and lonely – though occasionally lovely – Saddleworth Moor. More than anything though, it is a region defined by the Industrial Revolution, whose mills harnessed the power of water that surged down the steep valley sides to spin the wool and cotton that clothed an empire. Out of this emerged a new consciousness amongst the industrial working class, and Hughes’s writing on the subject is vital.

All of this takes place within an invisible triangle whose three sides reach only ten or fifteen miles in any direction, and is demarcated by memory and myth alone. But Millstone Grit is not merely about the darkness of the West Yorkshire/Lancashire borderlands, though naturally Hughes continually comes back to the broodily oppressive skies, the dank hidden corners, and the ever-present rock pushing its way through the topsoil and heather. How could he not?

This is an exploration of place, yes, but also a celebration of a place and the people who thrive here, too. Reading the book today is like walking a bridge between two worlds, Hughes crossing the widening chasm that emerged in the 1970s between an increasingly archaic past of austere churches, sootblackened buildings, harvest haymakers, mill-workers forced to mime their words over the noise of production, ubiquitous Methodism and pubs with tap rooms presided over by no-nonsense landladies like the one whose hostelry he stumbles into down a dark and cobbled lane, and an unknown future. Here is an England fading like an old photograph, and this stretch of the Pennines can only cling to the past with its gnarled fingers for so long.

The mills are all shut now and broadband wi-fi connects even the most remote farmsteads to a worldwide information grid. There are farmers I know who fly to Mexico for an annual fortnight’s holiday as respite from the winter gloom. The main roads see few horses and instead become clogged with commuters’ cars as they head to Manchester and Leeds to hot-desk in great chrome-and-glass cathedrals consecrated for the religion of commerce.

But beneath it all, the gritstone still sits solid. The River Calder and others like it are still prone to regular flooding, as if to remind all of the impermanence and vulnerability of what each generation considers ‘modernity’. Sheep still dot the hillsides, and the wind whispers through upland grass and heather. In these barren places time slips away and one is transported back to an ancient past where little else seems to matter beyond rock and rain, and where nature always finds a way through.

In Millstone Grit Glyn Hughes has captured a transitional period – as indeed all periods of history are – in a way that is beautiful and funny and poetic and moving and true. It is an immense pleasure to be able to help bring it back to life.

*

The Little Toller edition of ‘Millstone Grit’ is published later this month. Pre-order your copy here (£14.00).