Steven Lovatt watches salmon leap from the River Severn.

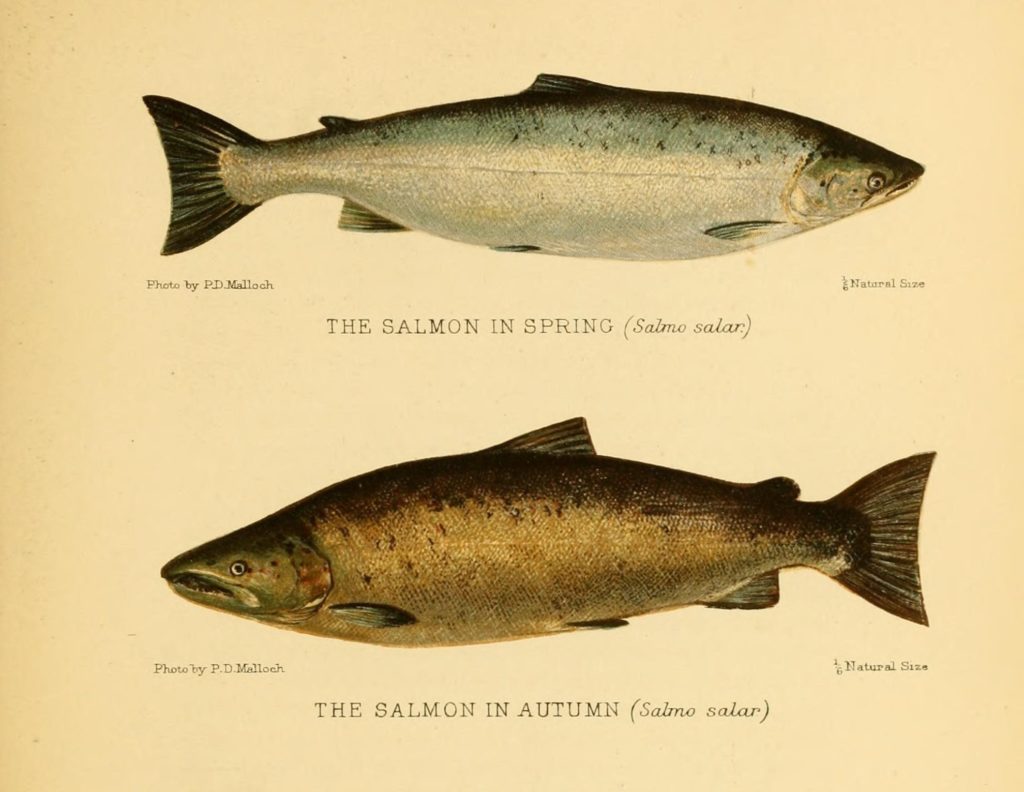

Plate from ‘British fresh-water fishes’, London, Hutchinson & Co.,1904, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library on Flickr

Each autumn Atlantic salmon gather in the Severn Sea and at the ordained time ride upriver with the tide. By October they have reached the weir at Shrewsbury, where from early morning people gather at the railings to look for them, mostly locals but also visitors like myself. I arrive first before eight. Beside me two infants and their mother take turns to study the water through binoculars made out of loo-roll tubes and string. For a long time there are no fish. Plump and comely woodpigeons scull through the cool air above the water to bellyflop for berries among the trees on the far bank. At ten the river bailiff crunches up in his 4×4. Nature and culture thrive or decay together, and there are fewer and fewer salmon on the river, and fewer bailiffs too. He’s a rarity upriver at Newtown, an endangered species at Abermule. Last year it became illegal to take home a salmon of any size. He scans the river and moves on.

All morning a relay of strangers become briefly companiable at the weir, carefully avoiding hand contact on the railing, shyly seeking one another’s joy when a fish flings itself from the water in athletic torsion. In the meantime the weir itself is mesmerising. It is like a great loom on which the river is worked into colour, from the slopping purple of the lip to the sudden acceleration into hissing white threads, before the final gush into dirty yellow foam. The force of the plash furrows the water and some that’s just fallen turns back to paw at the trench, as if regretting it. But at the very bottom of the weir the water is oddly calm, and that’s where the salmon gather strength. They have come a long way. From the open sea. From long ago. When they leap they look heraldic, the weir their tapestry. The people are part of the picture too. They have been watching salmon on the Severn for thousands of years, since the end of the Ice Age, when the river abruptly changed direction, abandoning its former northerly course to flow southwards and drain the great lake that covered much of Shropshire.

The bailiff can’t be everywhere. As the moon rises, hunched silhouettes appear in the riverside gardens. Each salmon can fetch as much as you’ll earn in a day’s work selling mobile phone cases. Just before I leave, a white-bearded man arrives and edges down to the riverbank with a fold-up fishing stool but no rod. Does he come here every year? He can’t hear me above the roar of the weir, so I repeat the question, feeling foolish for shouting. ‘Yeah, it’s a privilege, isn’t it.’ He glances at me very briefly, without curiosity, and turns back to the water. Fewer and fewer salmon every year but still they come, and their people too, until the end.

*

Steven Lovatt wrote ‘Birdsong in a Time of Silence’ and edited ‘An Open Door: New Travel Writing for a Precarious Century’. He reviews for The Friday Poem and does freelance copyediting from his home in Swansea.