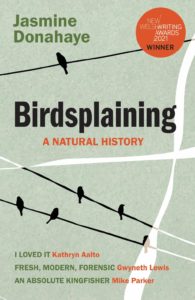

Jasmine Donahaye’s ‘Birdsplaining: A Natural History’, just-published by New Welsh Rarebyte, upends familiar ways of seeing the natural world — and in doing so, writes Karen Lloyd, creates its own ecological niche.

In nature, an ecological niche is the term used to describe the position of a species within an ecosystem, the range of conditions necessary for its perseverance and its role within a particular ecosystem. In contemporary publishing, all kinds of niches exist across a broad spectrum of what is commonly known as ‘nature writing’. At one end is the popular ‘nature recovery’ memoir (though why so many of these are deemed nature writing rather than memoir is beyond me) frequently perpetuating the idea that if a narrative takes place largely outdoors, then it must by default be ‘nature.’ Field guides, on the other hand, inhabit a niche at the other end of the system. Through meticulous attention to detail, they help shape our understanding and knowledge of species and the habitats they depend upon. Between these two exists a broad spectrum including enquiries into particular species, the climate crisis, landscapes, biodiversity loss, nature recovery and much more besides.

Largely concerned with the author’s home landscape of Wales, Jasmine Donahaye’s Birdsplaining: A Natural History is the result of decades of paying attention to the birds and mammals the author encounters around her home landscape and further afield. The book’s opening gambit, ‘Birds explain nothing to me,’ refers back to the title, which is derived from the term ‘mansplaining,’ where an explainer (usually male) assumes they know more than an explainee (usually female), assumed to know far less. In contrast, Donahaye’s processes remind me of a turnstone working the shoreline, its need to find the sustenance revealed by each new wave perpetuated because, well; its life depends upon it. The opening essay is concerned with a sister’s breast cancer, the tortuous mechanics of the breast scan itself and the stark reality of a diagnosis. In this context, Donahaye asks about the tendency towards superstition — the looked-for signs and portents that most of us privately indulge in at such terrifying times. ‘If the sun breaks through the cloud…if the traffic light turns green before I count to twenty-five…’ And whilst it might be considered strange to begin a book titled Birdsplaining: A Natural History with an essay that discusses breast cancer, what else is disease but part and parcel of the everyday natural world? What is the real meaning of a wren in a house, or a swallow or a polecat for that matter? Signs from nature are all around us — if only we care to notice and think about what they mean for us individually, collectively.

‘Field Guides’ is concerned with the way that ownership of knowledge has for so long remained unquestioned in the field of nature. Interrogating an edition of Collins’ Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe, recalled from childhood, a question shapes itself (something that was for me an ‘unthought known’) of why it is that the male of a bird species dominates a page of illustration, whilst the image of the female is smaller, usually behind or below the male, as if she is simply of lesser value or interest.

In ‘Mansplaining the Wild,’ much of which is concerned with a review of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild by US journalist Jim Hinch, Donahaye writes; ‘I particularly mistrust an approach to the natural world and wilderness as something transformative and spectacular, when it can just as often be squalid and mundane.’ But here’s the qualifier; ‘ When I say I mistrust those approaches and ideas, it’s because I know what’s going on when I myself take any of those attitudes. And I do take them — I take all of them.’ And what else is the literary essay itself, but a means of opening the self to scrutiny? Our faulty, unreliable selves indeed; the only true means by which we are capable of measuring anything else.

There’s an idiosyncratic and elegant curiosity at work here, whatever the subject; mice in the house, a rotting sheep’s leg, nightjars, puffins, gannets, crows flocking (and yes — it seems that occasionally, they do) unsettling encounters with others in lonely places, the unreliability of memory and even the ability to get things badly wrong. The ability to construct narrative not only from close investigation and — it should be noted, a sound knowledge of natural history — but also from self-reflection, self-questioning and uncertainty is a too rare thing, with those last three concepts so rarely adopted by male writers of nature. In combination though, and in Donahaye’s hands in particular, these are the tools for unlocking a specific subject’s DNA; for allowing us to see something anew, as if the sun had indeed come out from behind the clouds.

In ‘The Regard of Equals,’ after an encounter with a polecat, the subject of anthropomorphism appears. Donahaye asserts that to objectify an animal is wrong; ‘to reduce him to a thing, not a living creature to whom I respond in all the flawed and inadequate ways…I have…’ which she follows with ‘I experience his gaze as the gaze of an equal…I am, simply, observed.’ Elsewhere, a pair of ospreys at an RSPB site have been ‘anthropomorphised beyond retrieval by the public,’ and shortly after this, ‘The woodpigeon is not demented. The wren is not cocky.’ Indeed, all of us have all allowed ourselves to think otherwise; it is the training we receive from metaphor and the making of meaning. Underpinning everything in this book is the notion that to get at the truth of something it is first necessary to accommodate our own processes, be they messy, complicated and sometimes deeply uncomfortable.

With the thoughtfulness at work in this collection, Donahaye’s essays create their own ecological niche; a species of the nature genre rarely encountered, occupying its own necessary and important place in the system.

*

‘Birdsplaining: A Natural History’ is out now and available here (£9.99).

Karen Lloyd is the editor of ‘North Country: An Anthology of Landscape and Nature’ (Saraband, 2022) and author of the James Cropper Wainwright Prize longlisted ‘Abundance: Nature in Recovery’ (Bloomsbury, 2021). She is the writer in residence with Lancaster University’s Future Places Centre.