Ever decreasing circles: Mark Hooper takes a wrong turn on a Wiltshire canal path and ends up summoning aliens.

Some of the best walks are the ones you abandon or are forced to alter. Many a sudden downpour has hastened me into the pub for a brilliant impromptu evening; or prompted a change of route that has proven far more rewarding. In my early teens, I joined a school ‘Adventure Training’ trip to Wester Ross in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. (And if you were tempted to say that sounds suspiciously like somewhere from Game of Thrones — let’s just take a pause and think about why that might be.) This was in the late 1980s, when phrases like ‘health and safety’, ‘duty of care’ and ‘basic common sense’ apparently held less weight amongst the teaching community. As a result, a ragtag bunch of schoolchildren from Somerset were let loose on a series of Scottish munros (defined as mountains of over 3,000ft in height), led by two likely characters called Miller and Wrench. Miller was the spitting image of Mr Baxter from Grange Hill — a tall, languid, straight-talking type who had the disarming habit of talking to us all like adults, something we’d never encountered in a male teacher before. Wrench was bullish and stocky — he’d once played as a prop for England, and there was a rumour that he’d once bitten someone’s ear off in a scrum (when he heard this, he loudly denied it to dining room full of hundreds of children). I also witnessed him deliver the finest ‘swear swerve’ I’ve ever heard — loudly berating a schoolboy across the playing fields, he suddenly spotted the headmaster showing some parents round the school and changed his scream mid-flow so that it came out as: ‘FUC-rying out loud, son!’

Our week of Adventure Training included several aborted trips. One involved a trailer becoming uncoupled from a Land Rover, prompting Miller to calmly say, ‘Put your foot down Wrenchy, you’re being overtaken by your own trailer!’

That trip ended up with 30 schoolkids jumping out of an army truck and helping to haul the trailer out of a ditch.

Another time, it was my turn to be team leader for the day when we spotted a big squall heading in from the hills. After a brief conflab, it was decided that the kids would return with two adults, while Miller, another teacher and two kids who were more experienced climbers would sit it out under the shelter of a huge boulder to see if there was a break in the storm. As I turned to follow the retreating party, Miller called out to me — ‘You’re with us — you’re still team leader.’

As it turned out, after a heavy hailstorm, the clouds passed over us, to be followed by blazing sunshine. With the mountain to ourselves, we climbed snow-filled gulley to a stony ridgeway that lead us al’ the way to the peak — and stunning views for several hundred miles across the Highlands. Miller grinned at me and told me I was lucky to have been ‘volunteered’ by him that day, and then we took our plastic bivvy bags out and slid down the snowy hillside to the bottom. It was probably the best day’s hillwalking I’ve ever experienced.

My latest abandoned journey wasn’t quite so dramatic. We’d planned a gentle stroll along the canal path at Alton Barnes near Pewsey in Wiltshire — a pleasant springtime walk under the watchful gaze of the local White Horse, carved in the chalk above a Neolithic long barrow (the more famous West Kennet lies just beyond, as does Silbury Hill, the largest manmade mound in Europe, built around the same time as the pyramids at Giza).

But we didn’t get that far. As we set off, the drizzle got heavier. Becky was wearing white trainers. She slipped a couple of times in the mud — the first time was funny, the second time she nearly ended up in the canal (still funny). We passed a few dog walkers, in appropriate footwear. We got about 300 yards before deciding to head in the opposite direction. We were barely back to our starting point before we agreed it was pointless and retreated to where we’d parked the car, next to a café and a handful of independent shops.

Amongst these was the Crop Circle Visitor Centre. My knowledge of crop circles is pretty scant. They were big in the 90s, then two locals announced they’d done it all with some planks and lengths of twine, and the tabloids lost interest.

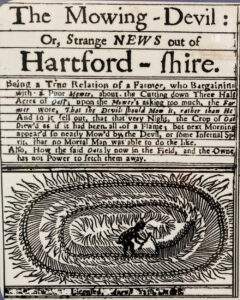

It turns out there’s more to it than that (who knew?). For a start, the earliest recorded reference to a crop circle is found in the report of a witch trial from 1590. The exhibition also reproduces an early news pamphlet report from 1678 entitled ‘The Mowing-Devil: Or, Strange NEWS out of Hartford-shire’, in which a farmer claims the devil himself has created strange patterns in his field of oat crops.

So, it seems not every crop circle was created by two locals armed with planks. Moreover, it still happens frequently, even if the tabloids don’t seem as interested these days. If you visit the centre’s website (cropcircleaccess.com), you will find a pop-up window (circular, natch) detailing all the ‘latest crop circle reports’ including information on when they were reported, whether you can access them, and a handy link to their location on Google Maps.

There have been many theories about how and why these mysterious patterns occur — and not every example can be put down to hoaxers. The East Field Pictogram — an elaborate, 600ft-long design that appeared near Alton Barnes overnight in July 1990 — can be described as the most significant crop circle of the modern era, and the one which first garnered global interest in the phenomena. (You definitely know it — it was on the cover of the Led Zeppelin Remasters album released later the same year.)

Theories abound about what causes them — from ley lines and geophysical anomalies to alien invaders. Some seem to be so obviously manmade that a hoax is the only answer, but farmers often report how their crops are flattened but not broken or snapped — suggesting ultra-localised whirlwinds might be to blame. This is something I’ve witnessed myself, and the sight of a mini twister working itself into a frenzy, seemingly from nowhere, and skipping across a field — even jumping over hedgerows and roads – is eerie to say the least. If I was a Jacobean farmer, I’d definitely think the devil was afoot.

To be fair, the centre isn’t as conspiracy theory-friendly as you might expect. Set up by Dutch-born Monique Klinkenbergh and researcher Andreas Müller, there is an emphasis on debunking myths and misinformation and introducing a more scientific approach — ‘and to emphasise that, alongside manmade circles, there is an authentic phenomenon at work’.

There is also an interesting thread about the impact that this all has on local farmers — from the damage to their crops and loss of income to the effect on their livelihood caused by sightseers trampling their fields even further. The advice is to always seek permission before attempting to enter fields — and to offer a donation to obliging farmers in return for access.

No firm answers are proffered, which only makes it more fascinating. Personally, I don’t think the devil or extra-terrestrial life are to blame, but there is definitely something deeply weird about this little corner of Wiltshire.

All I can say is it’s really hard to get a mobile phone signal.