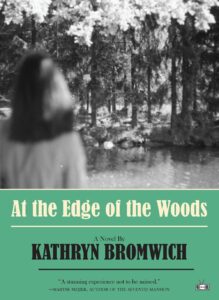

As disquiet gradually accumulates, Kathryn Bromwich’s debut novel considers how rejections of femininity can ignite a hysteria, writes Abi Andrews.

I will be adding At The Edge of the Woods to my pile of beguiling peasant novels that have nature as an active presence (between Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plough Over the Bones of the Dead and Solà’s When I Sing the Mountains Dance). Kathryn Bromwich’s debut follows her protagonist Laura, a thirty-something woman living alone in a cabin on a mountainside, at the edge of a forest, above a small village in the Italian alps, at the beginning of the 20th century. The village is quaint and superstitious, and Laura has recently moved to the mountain to escape something in her recent past. She quickly slips into her life in the cabin. The villagers are affronted by a woman living alone (in order to rent the cabin she told the landlord her husband would soon join her), and her visits to the village are perfunctory — to pick up supplies, translation work, and to keep up the appearance of sociality.

Bromwich’s pace is skilful: we slide without quite noticing from the cabin and the forest on the mountain as an idyll, with gorgeous descriptions of Laura’s daily hikes, to a gradually accumulating sense of disquiet. Laura’s solitude is at first liberatory — especially for the times the novel is set in — and she seems so at peace that you might want her to never enter the village again. We settle into the cabin with her, feel the chafe of the village with her, willing her to get back to the mountain, go out for a walk and tell us about it. This is contrasted with the anxious expectations of her past domestic life as wife to a cruel and wealthy man, who wouldn’t let her walk alone. The forest seems a promise that our human dramas, if they get too much to bear, can be let go of, lost in the natural world’s indifference. We feel frustration at the discrepancy between the way she lives up there, in the community of deer and peonies and wolves and vegetables that she is forging at the edge of the woods, and how people think she ought to be living; her life, even in solitude, shaped by the expectations of others. The spectre of patriarchy looms over the novel, its threat beneath comments like “you’re all alone up there” from the village men, its shadow becoming suffocating as the novel goes on.

Laura uses laudanum to ease her anxiety. Her increasing use of the drug coincides with her mental deterioration, although this is ambiguously played, and perhaps deterioration isn’t it, because under its psychedelic influence her world is allowed to remain spectacular, becoming Ovid-like, hyper-fertile, technicolor. Bromwich does the liminal very well, potentially because she doesn’t dwell too much on its significance or overdo it; this is a short and punchy book. It is left to the reader to decide how much of Laura’s hallucinatory bent is a result of trauma, laudanum-induced hallucination, or a magical realist revelation of her witchiness. Does the weather change with her moods or do her moods change with the weather? It is a fascinating thought experiment on how superstition can bring about its own demons – and how rejections of femininity can ignite a hysteria. We are invited to decide how much to read accident as curse and how much curse disguised as coincidence, as stranger things start to happen in proximity to Laura. All building up to a crescendo that is left open, but doesn’t feel inconclusive.

*

‘At the Edge of the Woods’ is out now and available here, published by Two Dollar Radio.