Between Tesco superstores and mid-century blocks in north west London, Marcus Liddell searches for an ancient earthwork.

Standing on a railway bridge near Pinner I looked towards the large Tesco supermarket across the Metropolitan Line. It appeared to stand directly on land once crossed by the ancient Grim’s Dyke. But despite a check against my homemade map, I could not be sure. Even in 1935, Horace J.W Stone described locating this section as ‘very problematic’, and subsequent development had only increased the difficulty.

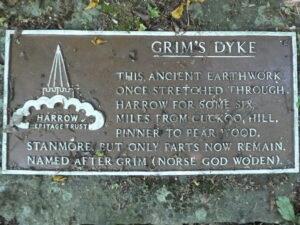

I had more luck in Montesole Playing Fields. Covered in trees, undergrowth, and specked with the usual litter of a suburban park, it might have passed for a mere mound of earth. But once you had seen it, or read the well-placed Harrow Heritage Trust sign, there was no doubting it was an ancient earthwork.

While today it separates the edge of the recreation ground from a block of early 1960s flats, it may once have marked an Anglo-Saxon, or even Iron Age, boundary. The earliest document mentioning its name, Grim’s Dyke, dates from AD 1535. Grim was an old word for Odin, the Scandinavian god, who the Anglo-Saxons called Wodan. The name Grim’s Dyke is used for several ancient earthworks in England but it is hard to draw firm conclusions about what this tells us about their origins.

At Montesole Playing Fields, you can walk along the bank’s crown for about 200 metres. I did my best to ignore the dead cat, discarded in the undergrowth, as I followed the small path between the trees of Dingles Wood. The embankment ended abruptly when it reached an abandoned chalk mine. I cautiously negotiated its banks before emerging into the park, close to some allotments.

Many questions remain about the earthwork’s origins and the information vacuum has enabled imaginative interpretations to flourish. In the 1930s, Mortimer Wheeler said Grim’s Dyke could relate to the Chilterns Grim’s Dyke and an earthwork called Faestendic in Bexley. Together they might link to the territorial privileges of post-Roman London, Wheeler suggested. More recent work contradicts this interpretation. In The Archaeology of the Dykes, Mark Bell, said the Chiltern Grim’s Dyke might be a series of local monuments rather than a single earthwork.

I had to walk about a mile to find the next surviving section. Even in 1935, when fewer houses had been built, there was no trace of it between Dingles Wood and Hatch End. According to Horace J.W Stone’s survey, The Pinner Grim’s Dyke, it recommenced on the east of Woodridings School for Girls. The school had closed since he wrote his account, but an old OS map, published in 1936, showed the dyke close to Altham Road.

Many more houses stand in the area so I was not hopeful of finding any sign of the dyke. Nonetheless, there was a narrow path which seemed to follow its course. I headed down the alley. I was fairly sure it was a footpath. But as the sound of a family eating lunch drifted over the wooden panel fence on my right, I began to wonder if I was about to enter someone’s garden. I was still preparing my excuses when the path opened onto a dead end and a railway bridge. A Harrow Heritage Trust plaque, on my left, proved my journey down the alley had not been wasted.

I crossed over the West Coast Mainline. The modern rail artery must have severed the ancient embankment when it was built in the 19th century. There was no sign of it on the other side of the bridge either. And yet, I was hopeful I might catch a glimpse in Sadlers Mead Open Space where a sign on the gate advertised the playing fields as the ‘Historic site of Grims Dyke’. I found the earthwork, about two metres high and fronted by a small ditch, next to a cricket pitch. The players of each team were too focused on the next ball to notice a man taking photos of the earth bank beyond the boundary.

There was less sporting action at nearby Grim’s Dyke Golf Club, where the warm weather had driven the players to the club house. It was so quiet, I was almost tempted to trespass over the fairways in search of the earthwork. But I have never been a natural rule breaker. And the thought of having to explain myself kept me to the footpath as it crossed the course and entered the grounds a Best Western hotel.

Whether the dyke continued any further beyond the grounds of the hotel is debatable. The brown Harrow Heritage Trust signs I had intermittently seen along my walk said the dyke ran to Pear Wood, where another earthwork stands. The heritage signs also suggest it dates from the fifth or sixth century. But, of course, little is certain when it comes to ancient earthworks. Charcoal, from the remains of a hearth, found in excavations near Grim’s Dyke Hotel in 1979 was carbon dated to the Iron Age. Pottery sherds and Iron Age flints have been found at Montesole Playing Fields as well. It potentially conflicts with evidence from Pear Wood where Roman pottery sherds were found.

I might have ended my walk outside Grim’s Dyke Hotel, satisfied I had covered its course. But I decided there was enough doubt to justify walking the extra two miles or so to Pear Wood to see the final embankment for myself. The journey took me through the grounds of Bentley Priory, land once belonging to a cell of Augustinian Canons, and across Stanmore Common. The views over north London were as good as any I have seen and merited a trip on their own.

Surrounded by trees, in Pear Wood, it was hard to believe I was on the edge of London. I was reminded of afternoons spent tracing old Roman roads in Hampshire woodland. The only giveaway was noise from the A5, the modern incarnation of a Roman route linking Londonium with Verulamium (St Albans), also known as Watling Street.

I paused on the crown of the dyke and vainly tried to comprehend the earthwork’s antiquity. The bracken, billowing from its banks, was shining bright green in the late afternoon sun. A few more minutes passed before I turned back to common and walked the short journey to the northern terminus of the Jubilee Line. I was no closer to understanding Grim’s Dyke but I will never look at the words Pinner, Hatch End or Stanmore on a tube map again without thinking of this enigmatic earthwork.

*

Marcus Liddell is a former local journalist turned history teacher living in west London. He is particularly interested in the physical legacy of the distant past (old Roman roads, ancient boundaries, medieval churches etc.) He has previously written for BBC News online, Unofficial Britain, Walk, and the Londonist.