Following in the footsteps of Syd Barrett, Travis Elborough negotiates the ley lines, Chinese takeaways and automotive detritus of the A10.

I normally tell people I grew up beside the sea. But it’s perhaps more accurate to say I grew up beside the A27. The relentless tides of traffic on this road — which straddles the length of the south coast from Hampshire to East Sussex — were as much a constant feature of my childhood as the waves on the local beach. Similarly today I say I live In Stoke Newington. But really I live on, or just off the A10 on a street that I have heard other people claim for ‘Dalston borders’ or even maintain is ‘nearer to Newington Green’. The A10, once the rather more romantically titled Ermine Street to the Romans, nevertheless, is a constant presence and the track that has guided my direction of travel for nearly twenty years now.

More recently, though, I’ve become much more interested in the A10’s course beyond the capital and out to the fens. Last year, aside from contracting Covid and cursing Boris Johnson and his government, I’d been working on a script for Have You Got it Yet?, a new documentary about the Cambridge-born artist and musician Roger ‘Syd’ Barrett — the original frontman of, and main songwriter in, Pink Floyd and a figure I’ve been fascinated by ever since hearing the group’s 1967 debut album, Piper At the Gates of Dawn, as a teenager in the 1980s. Barrett, for those not familiar with his slightly tragic story, was ousted from the band in 1968 amid rumours of an LSD-induced psychotic breakdown. And after producing two startlingly brilliant, if haunted-sounding, semi-acoustic solo albums with the aid of his former bandmates, withdrew from the music business entirely in 1972. Subsequent reported sightings, rightly or wrongly, were to turn Syd into one of rock’s most notorious acid casualties. The once elfin singer of whimsical psychedelic nursery rhymes and pioneer of cosmic space jams was by 1975 catatonic, shaven-headed, balding, and so grotesquely corpulent he was initially all but unrecognisable to Pink Floyd’s Zapata-moustached drummer Nick Mason. Said to be subsisting on a diet of Guinness and pork chops, infamous stories of him biting the hands of music publishers, renting apartments just to fill them with guitars and then giving all his possessions away, were legion and only further burnished the legend of the reclusive genius whose mind was blown. After close to a decade living in various flats (and indeed sometimes multiple ones at the same time) in Chelsea Cloisters, the ocean liner-esque 1930s modernist block on Sloane Avenue, and having previously come close to financial ruin, Barrett checked out in 1982 and left London for good. He walked the whole way home to his mother’s house in Cambridge. His sister Rosemary recalled him arriving, his feet raw and blistered from the trek.

His most thoughtful and thorough biographer Rob Chapman draws a comparison between Syd’s schlep home with that of the ‘mad’ Romantic poet John Clare in 1814. The latter trudged on foot back to his native fenland village of Helpston after absconding from Matthew Allen’s asylum near Loughton in Epping Forest, a journey whose course along the Great North Road, Iain Sinclair, that godfather of psychogeography, retraced in his book Edge of Orison. And in a similar spirit, I’d been spending the summer of 2022, forty years since Syd himself stepped out the door of Chelsea Cloisters, covering sections of Barrett’s walk from London to Cambridge, his route, naturally, also mapping the contours of the A10. But for the A10 Live, a project involving fifteen writers, poets and artists tackling different sections of the road, I would be going beyond the City of Perspiring Dreams to Milton and out to Ely and travelling much of the way by bus accompanied by the Stoke Newington Literary Festival director Liz Vater, who was to document our progress as we went along.

Typing ‘ELY’ into my phone a few days before setting out, my finger slipped and I wound up putting ‘LEY’ into Google instead. It seemed fated somehow. Alfred Watkins, the Hereford brewer, apiarist, antiquarian, advocate of wholemeal bread and women’s suffrage and keen photographer who developed a light meter that polar explorers like Scott took to Antarctica with them, first posited the idea of Ley lines back in 1921. On the warm summer afternoon of 30 June that year, Watkins had been out walking near an Old Roman settlement at Blackwardine in Herefordshire. As he made his way up a hill and looked down, he had nothing short of a vision, suddenly seeing in an instant a network of underlying prehistoric tracks that joined up the dots of all he surveyed. What he came to call ‘leys’ or ‘ley lines’ were supposedly linear pathways aligned with the features of the landscape and that linked holy places, mounds, old crossroads and other sites of antiquity. Watkins would expand on the theory in his 1925 book, The Old Straight Track — a volume that would go on to become almost a set text in the hippy countercultural circles that Syd Barrett moved in. Ley lines and stone circles joining astrology, the I-Ching and eastern mysticism, UFOs and cybernetics as key topics in the lingua franca of the underground.

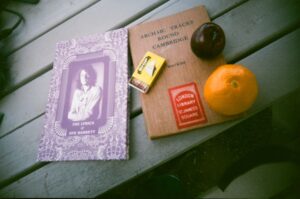

As it happens, though, there is also a Cambridge connection to Watkins. By 1931, Watkins’ son, Allen, was living in the city and at his dad’s behest, carried out investigations into ley lines in the local area. Allen’s first major ley hunt was to begin off the A10 at Royston and Watkins senior, after visiting his son, compiled and published Archaic Tracks Round Cambridge, his survey of the county’s leys. Consulting the book, which discusses the ‘prehistoric origins of the four great roads, ’Watlinge strete, Fosse, Hikenilde strete’, and thankfully, ‘Erimine Street’, I noted that one of Watkins’ ley routes appears, at least, to begin in Milton, the village where the bus part of my journey along the A10 was due to start. I took this as another omen of sorts and tucked Archaic Tracks Round Cambridge into my army surplus bag for the ride.

There was also a pub in Milton called The Lion and Lamb that I was quite insistent was added to our A10 itinerary. As it was here that in May and June 1964, the eighteen-year-old art student (and then still) Roger Barrett staged a joint exhibition of his paintings with his friend Anthony Stern entitled ‘Two Young Painters’. Accordingly I packed a print out of the flyer of their exhibition, a book of Barrett’s lyrics and my trusty Sony cassette walkman and a tape of The Division Bell. This 1994 release is one of Pink Floyd’s later efforts and was recorded over a decade after the departure of the band’s other significant Roger: bassist and founding member, Waters. Yet it is an album that has stood up rather well and whose cover was designed by the group’s old Cambridge contemporary and long-term collaborator, the late Storm Thorgerson.

At the centre of that sleeve, most importantly for my excursion, is Ely Cathedral, which appears in the far distance and framed by two giant Easter Island-style heads standing in the low fenland landscape and canopied by a vast open expanse of blue sky and some tufts of clouds. The peal of church (possibly even cathedral) bells equally compellingly open the album’s closing track, ‘High Hopes’, an epic and deeply moving, seven and half minute long hymn to lost innocence, youthful ambition and Cambridgeshire itself. The song mourns the passing of ’nights of wonder’ when ‘friends surrounded’ and days of yesteryear when ‘the grass was greener’ and ‘the light was brighter.’ Like Pink Floyd’s ‘Shine on You Crazy Diamond’ from 1975, it is a number that also pays direct tribute to the fallen Syd and references one of Barrett’s most enduringly popular songs, ’See Emily Play’ – a top ten single in 1967. For good measure, therefore, I added a plum, a box of Ships matches and orange to my luggage. A holy trinity of objects that Syd notoriously became captivated by during his first acid trip, undertaken with Storm in 1965. And items that the designer later incorporated into artwork for a double compilation album of Barrett’s solo records. Finally I bunged a compass into my bag, while knowing full well we’d have Google Maps up and running on our phones but sentimentally clinging to the notion that we were pilgrim wayfarers of an earlier age.

The train from Liverpool Street deposited us outside the old city limits at Cambridge North railway station. A comparatively recent addition to Cambridge’s transport network, it only opened in 2017, and is large, boxy but quite airy and composed of a lot of silvery metal grilles and glass. Outside the station there was a plethora of billboards with words like ‘innovation’ ‘new’ and opportunity’ on them promoting Cambridge North as an up and coming destination, accompanied by images of gleaming new build offices, flats, coffee shops and landscaping near some actual new build offices, flats, coffee shops and landscaping in various stages of construction. We followed a sign and headed up a long narrow and boring path intended for cyclists and pedestrians, though we encountered none of the former, to reach the Cambridge Science Park. Our plan was to walk from here to Milton and then take the bus to Ely.

Etymologically our word ‘park’ comes from the Norman French for ‘an enclosure for beasts of the chase’ and is related to hunting, hence ‘game’ as both a meat and a sport. Naively, perhaps, I had hoped that the Cambridge Science Park might be a kind of al fresco Science Museum with some interactive displays and the odd Stephen Hawking-inspired ride. (Hawking’s computerised voice, by the way, also appears on the track ‘Keep Talking’ on The Division Bell.) But alas Cambridge Science Park, like its near neighbour, the Cambridge Business Park, was a cluster of impressive enough-looking facility-type buildings set in a park-ish expanse of roadways, grass verges, and trees. After consulting Google Maps and the nearby road signs we headed off along a section of the A10 humming with traffic in the direction of Milton. Soon we came across a modern bus shelter, its clear plexiglass canopy gaily decorated with illustrations of herons and reed beds. This folksy imagery was in jarring contrast to its surroundings, with lorries thundering by only inches away. An information board informed us that the next bus was due in 44 minutes; at my own end of the A10 a bus is rarely longer than 4 minutes away, I mused on the pace of life here. Perhaps less is more out here in the Fens. But I suspected, given the speeding vehicles within sight, that the urge to get from A to B was no less urgent here than in London and that bus users were simply being fobbed off with a less regular service.

As we walked along the road we felt ourselves being pulled toward the approachway of a large roundabout, one that seemed to squat on the near horizon like a death star drawing vehicles relentlessly into its orbit. The territory by now had become far less forgiving for pedestrians. Much more J G Ballard than Barrett in fact. Which might well be apt since the prophetic dissector of the media-saturated urban environment and author of the auto-erotic Crash and Concrete Island (effectively Robinson Crusoe in asphalt), was educated at The Leys School, Cambridge (yet another ley), and studied medicine and English at the University. Such coincidences came as little comfort however, when we came to a barrier and a sign informing us that the footpath running alongside the next stretch of dual carriageway was closed. With no other option other than walking on the road itself, we hopped over the barrier and continued on our way along the path. This was overgrown with mossy grass and, more worryingly, littered with fragments of wheel trims, tail lights and car bumpers. The presence of so much automotive detritus suggested the line here between road for cars and, albeit officially closed, path for pedestrians was rather more porous than it ought to be. Still we gamely battled on clearing more roundabouts and negotiating flyovers and verges to reach the turn off for Milton’s High Street and that most emblematic of roadside attractions: a burger van.

Once on the High Street, a far narrower and much quieter and much more residential road, the overriding sense of automotive menace quickly fell away. Though passing by a small industrial estate we narrowly avoid colliding with a trio of women joggers in fitness gear who appeared to be heading, at quite a clip, to a gym housed in one of the factory-like sheds. Weary from having negotiated what seemed like several circles of dual carriageway hell, their perkiness — and one of them paused to bounce on the spot and roll her eyes before darting past us — only served to make us feel even more exhausted as we trudged on in search of The Lamb and Lion pub and the promise of food since it was already getting on for 1pm.

Milton, which was quaintly village-y in places with an antique shop and a few older cottages and some kind of chapel, didn’t appear short of pubs or culinary options. On the takeaway front and just a short way up the street we found a fish and chip shop and a Chinese restaurant right next door to each other. Near identical red and white signs gave their names as ‘Jaws Fish & Chips’ and ‘Unicor House’. A faded outline confirmed a missing ’n’ in the English part of the latter’s sign. Though no letters appeared to be missing in the Chinese script beside it, so perhaps it’s still Unicorn House in Chinese. Or maybe it goes by another name entirely for Chinese speakers. I remembered that Unicorn was also the name of a band that David Gilmour of Pink Floyd produced in the 1970s. But I instantly dismissed this thought as a coincidence too far, and reminded myself that constantly looking for connections where none exist is a definition of madness.

Despite an inviting set of brass lamps above its front door that lent it the air of a coaching inn from the era of Dickens’ Pickwick, we chose to forego The White Horse pub after spying The Lion and Lamb on the next bend in the road up ahead. It too had lamps (though not brass) and such a ye olde country pub look to suggest its roof should be thatch rather than tiles and that a hunting party in scarlet duds was due any minute now. Patriotic red white and blue bunting was much in evidence, the aftermath of the previous week’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations. Inside there was a pleasing amount of black beam, white plaster, bare stonework and brick. The decor, though, was standard pub fare, a few historic scenes and local trinkets. It was hard to imagine Syd’s adolescent paintings, few of which survive, while only poor black and white photographs of others remain, gracing these self-same walls. But according to Will Shutes in a monograph on Syd’s visual output, The Lion and Lamb was then ‘a port of call for a group of local artist friends’ and after the landlady Barbara Patterson mentioned she’d like some art for the pub’s walls, regular monthly exhibitions were organised for about two years by the artist and writer Antony Day, with ‘pictures distributed round the bars as there was no separate gallery’. Esoteric events of a sort, though, still seem to be a feature of the pub’s life. A chalkboard promoting a Psychic Supper evening with a clairvoyant was hung up near the fireplace.

Since it was a pleasantly sunny lunchtime, we went out into the garden, which appeared extremely well-equipped for outdoor drinking and dining with decking, tables and umbrellas and a dedicated garden bar in a wooden outhouse at the back. We wondered if the garden had been quite so well-equipped before Covid-19 and judging by the newness of some of the woodwork, concluded probably not. A dusty-looking gigantic tub of hand sanitiser sitting on the bar, which for the duration of our stay here remained undisturbed by human hands, appeared another legacy from the last couple of years. Conscious of the irregularity of the bus service and after consulting the timetable, we ordered lager and chips for ease and speed, with the aim of catching the next number nine to Ely in about 50 minutes’ time. I ceremonially laid the orange, matchbox, plum and my books on the table and took a couple of photographs to serve as mementos of the visit.

*

Described by The Guardian as ‘one of the country’s finest pop culture historians’, Travis Elborough has been a freelance author, broadcaster and cultural commentator for over two decades now. Elborough’s books include ‘Through the Looking Glasses: The Spectacular Life of Spectacles’ and ‘Atlas of Vanishing Places’, winner of Edward Stanford Travel Book Award in 2020.

Visit his Bookshop.org page here.