As Smithsonian Folkways reissue a croaky classic, Mike Gavin gives his ears over to poetically narrated amphibian song.

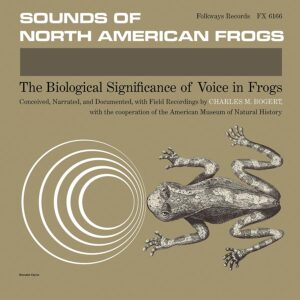

My fascination with what you might broadly call nature sounds started in the un-natural environment of the basement of Ray’s Jazz Shop on Shaftesbury Avenue, which I ran as Ray’s Blues and Roots in the 1990s. My idea (if not owner Ray’s) had always been to broadly define ‘roots’ or ‘folk’ music to include field recordings on treasured labels such as Ocora, Chant du Monde, Wergo and of course Folkways – perhaps the strangest and most esoteric label of them all. At that time the Folkways archive had gone to the Smithsonian and CDs started to appear, seemingly randomly curated, from that rambling and catholic archive. Among the first was an album that immediately piqued my curiosity: Sounds of North American Frogs — The Biological Significance of Voice in Frogs. Conceived, Narrated and Documented with Field Recordings by CHARLES M. BOGERT, with the cooperation of the American Museum of Natural History to give its glorious, full title.

OK — an album of frog sounds, whilst diverting, might fail to hold the attention for long. But this album’s secret weapon was narrator Charles Bogert (surely an aptonym!). His hip recital, dust-dry in contrast to his subject’s lubricity, gives the recording the authority of a poetic work, as if a Burroughs or a Hemingway had a ranine inclination. It’s mesmeric and truly rhythmical.

The sleeve notes also elevated this production from the common and garden frog recording: ‘It is probable that the first voice in existence was that of a frog’. Bogert speculates that in ancestral humans’ primordial state the sound of frogs and toads was almost certainly an aural experience shared with inhabitants of the current anthropocene, and somehow that we are the better for it.

I was familiar with Dr. Roger S. Payne & Frank Watlington’s Songs of the Humpback Whale — a fixture in every hippy home in the ’70s. Playing the subsonic sections of this LP with the bass up through my old speakers — feeling the air throb around me was a thrill. I heard tell on the strange pre-internet grapevine of record nuts and esoteric musicians of some of the other extraordinary non-musical Folkways albums like The Birds World of Song: Listening through a Sound Microscope to Birds around a Maryland Farmhouse by Hudson and Sandra Ansley (1961 — A ‘sound microscope’?), An Actual Story in Sound of a Dog’s Life by Tony Schwartz (1955), Voices of the Satellites by T.A. Benham (1958 — one track features the audible heartbeat of Laika, the first dog in space) and Sounds of the Sea, Vol 1, Underwater Sounds of Biological Origin (1952). I was also listening to that cardinal and magical Folkways issue, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, just then newly reissued in a beautiful box set. Clearly there was something else other than actual nature or musical recordings, going on here. Encouraged by the vision of Folkways founder Moses Asch and his ‘World of Sound’, left-field scientists and social and cultural experimenters were going out there and asking deep and provocative questions of their material.

Around this time I also discovered the natural history department of Foyles bookshop on the Charing Cross Road, around the corner from Ray’s. This was during the reign of Christina Foyle when you had to queue to get a voucher before paying and when the shelves groaned with long out of print books that sat unsold. The natural history section included albums and CDs of nature sounds: The bird song of Papua New Guinea in multiple volumes; the Life of A Sea Slug — a video I think (my memory might be slightly overheating here). Even a ridiculously expensive recording of the inaudible sounds of the ocean. A treasure trove, overseen by a severe, bespectacled salesperson.

I stocked a small section of the shop with titles I could get hold of. Like-minded friends gathered to listen to these amazing albums (though rarely to buy — these artefacts weren’t going to make Ray’s fortune). I don’t think we were alone and it’s no surprise that the next generation of music makers started to mine these sounds. Of course nature sounds had always influenced composers. Luc Ferrari (‘Presque Rien n°1, le Lever du Jour au Bord de la Mer’, 1970), Ottorino Respighi (‘Pines of Rome’, 1924), and Beatrice Harrison’s nightingale duet in 1924 amongst many others. Sweet People went Top 5 in 1980 with their track ‘Et Les Oiseaux Chantaient (And the Birds Were Singing)’, presaging the deluge of nature sounds mood playlists of today. But a new wave of musicians who found their inspiration from nature, and who used new technologies to incorporate the actual sounds into their music, appeared. Works such as the fabulous Be – One soundtrack to artist Wolfgang Buttress’ bee hive installation, or ‘interspecies musician’ David Rothenberg’s improvised duets with birds, sea mammals and bugs and many others were in the lineage.

Folkways celebrates its 75th anniversary this year and to mark that milestone Smithsonian is, appropriately I think, reissuing Sounds of North American Frogs on LP — and, with a nod to the impact the album has had on contemporary artists, the electronic duo Matmos, with guest sound artist Evicshen, has been commissioned to take sounds from the Folkways nature and science catalogue and weave them into their dance music routines. The resulting album Return to Archive is out now, and the first single, ‘Why?’, takes Bogert’s recordings from 1958 and processes them into new and exciting shapes: ‘…the resulting array of noises generated by every frog species from all 92 tracks of the entire sprawling double LP were cut together, looped, and layered into the chorus of frog-patterns heard on this song.’

The LP reissue and Matmos disc will, with luck, generate more interest in this extraordinary album, and in the others on Folkways and elsewhere and initiate a new generation in the wonders of nature sound recordings.

*

Both ‘Sounds of North American Frogs’ and ‘Return to Archive’ are out now on Smithsonian Folkways.

Mike Gavin ran Ray’s Blues & Roots record shop in the 1990s. He now runs Cadillac Records and Ogun Records.