In her latest dispatch from Dartmoor, Kirsteen McNish makes new ritual stitches in the seams of the hills.

It is very early when I rise and the last of the stars are fading. I pull my trainers on and set foot up the steep hill to the church that looks over fields that remind me of Paul Nash paintings. At night I trace their edges in my mind to lull myself into slumber in the dark, where I can’t see anything other than the bleed of light from the window’s edge.

I have decided to walk first thing every day, dissolving thoughts into the constant rivulets of water that trickle down the roads like fish scales over criss-cross ridges on the road left by farm vehicles. Some days my eyes are bleary-feeling, Vaseline coated, and I must cajole myself: other days I almost skip up the road, there is much to catch hold of my imagination when looking at the same scenes in their minor and major lifts. I take a breath at the top of the hill and look over to the distant vale within which the “eye-field” I love so much seems to peer over the hamlet like a seal of protection. It is seemingly unchanged until the light oozes over it as the clouds shift — so much so I half expect a door to slowly draw open. I have been here a year, and I can’t find out much more than a self-published book on the place I live. I want to know its long held, well-kept secrets. My brother finds a bent and worn 17th century French coin from detecting in the fields, and we sift around online but find no real clues as to how it might have ended up here in the pregnant earth, perhaps dropped by a trader or soldier and hit by the plough, defaced as a sacrifice to win favour with fate, or a lover’s token – it feels sandy rough between the pads of my fingers. My limbs, organs, sinews and bone are tramping these pathways and fields like countless limbs have done before me. Flexing physically seems essential when emotions are as wired as the lines on my palm. I leave no trace but tread out whispered invocations with each footstep like scattered dandelion pappus. Peace now, peace now, peace now.

After living here for a year or so, I start to experience memory flashes telling me I managed to force the door shut on my last home, determinedly etching my chiselled route through stone. But now they rise. Certain conditions of light seems to be the thing that reminds me of a road or park or a person, slivers of time standing alone in galleries, shadows on the underside of bridges over the arterial Thames, and the rattle and shunt of the overground as it hits the marshes at dusk through silted windows. I think of climbing the ancient tower of the Garden Museum and how my fingers twitched with an overwhelming impulse to touch the canvas of the Cedric Morris painting I loved so much which was housed within its walls, next to a score of artefacts.

There is a blankness to the sky that entrances me at this time of year as it starts to turn colder. An empty sheet of promise as everything returns to the earth. Only now in the first days of November do I see the colours changing which feels like a tardy farewell to summer again — the wind suddenly hits one window in the kitchen hard like a huge vacuum, and moments later the room is flooded in blinding, low-hung sunshine. Only my hands tell me the temperature is dropping. Late autumn is full of golden-lustred pockets of light dancing on moss-laden walls. Green upon olive upon russet upon gold shines against the marble clouds. I realise I haven’t been to the coast in three weeks now and I can feel the ache deep in my marrow. As I meander these lanes, I think of one friend who has undergone gruelling major surgery, another who has had a longed-for baby, and I send photos of the of light dancing when really, I want to be right beside them. But soon.

With my provisional licence I drive through Dartmoor one weekend with my partner and kids and feel a slow exhilaration — I could take off from this road, such is the feeling of finally doing what I have put off for many years through fear and avoidance. Decades of riding a bike and using public transport and now becoming a car user feels like a backward step but my daughter can no longer be carried, and her legs or wheelchair can only carry her so far now we are here in the long lanes with high hedges. Pushing her wheelchair up these hills and down dales in the summer holidays left me as crooked as a crescent moon. The colours of rusted crackling bracken and gorse flood before me, the hills slide away into the rear-view mirror, and I manage to curve around Dartmoor ponies and grazing bemused sheep. Everyone else in the car is silent in the flood of colour, and I feel a creep of satisfaction despite the fact I know I am still gripping the wheel too hard. We are the invasive species here amongst the vast expanses of the moors forged from spewed magma and volcanic rock shaken inside out, with spectral sculptural trees studding the granite ridges.

*

A month before the rains came my daughter is admitted as an emergency case to hospital for three days, after barely sleeping for weeks. In an unseasonably hot October day in her room waiting for consultants, I feel a slow panic rising in the depth of me, like oil separating from water. I hear adults talking in low tones behind their thin curtains, soothing their children whilst I play music in her segregated room to try and cheer her. Harry Styles, Lankum, Janelle Monáe, Kathryn Joseph, Brian Eno and Khruangbin are amongst her jumbled mix – not artists I would necessarily expect to see nestling against each other neatly like starlings on a telegraph wire, but freer than my 11-year-old son’s self-conscious playlists, compiled studiously in his room. There is nowhere quite as sobering as a children’s ward, and I start to feel increasingly suffocated sat in the (p)leather easy chair which feels like it’s swallowing my will. My daughter is over-compliant, unusually quiet and much stiller aside from her intense hand wringing, evidently denoting surges of pain. Medics come and go, talking over and through her like a soundproofed screen has been erected – I look at them and her, expecting them to realise she is silent but still there. I also realise that the key I thought I had to her I can’t always turn. A young nurse with a broad Midlands accent, dewy skin and a jaunty ponytail visits us and tells us as she does obs, that she has a disabled elder sibling. She shares a few illuminations from childhood, and expresses her deep respect for her careworn mother. I marvel that as a child carer she has gone on to become a nurse, empathy deep in her metal. I always feel a weird mix of comfort and disconsolation exchanging stories of caring – a partially resigned inevitability to what society cannot adequately support and the knock-on effect of one’s own desires and free will becoming partly submerged like an iceberg. It is also a honeyed relief to talk to someone with the blinkers off – and as she strokes my daughter’s hand and addresses her directly, I am temporarily lifted, leaf-like, in this cloistered room. She suggests we take ward leave, sensing my jitters, and my daughter rocks forward in her wheelchair in agreement and propels the wheelchair, suddenly jamming it into the narrow door frame.

Once out of the windowless strip-lit pale green corridors, past patients pacing the roseless gardens below in loose-hung dressing gowns, I cannot get her to the nearest beach quick enough. Huts in neat lines sit by the promenade and a steam train chunters past on the cliff overhead. Families splash in what looks like a postcard from the Amalfi coast, such is the unreal shade of the turquoise water and the heat bearing down. I feel like we have been superimposed onto the beach, green screen cut-outs on the wrong collage – I’m in long sleeves and trousers from dressing in the cool of the early morning, my son cutting a louche Lou Reed figure in dark sunglasses and vintage jeans in the shade of the seawall, my partner wired and quietly clasping his fourth coffee. My daughter is pale and in discomfort and hasn’t given me eye contact in hours. I take her shoes off but she neither looks towards the sea or wiggles her toes in the sand; her chin points down to her ribcage instead. I feel a sudden panicked urge to bolt. A few hours later I push down a sob in my throat as my steady partner takes her back into hospital and I realise I have hit my own sea wall, accepting I can’t always fix it, fix her, or come to that, anything else.

*

A week of friends crammed into our house in makeshift beds concretes that I want more of the fullness of face-to-face meaningful exchange and less tapping out thin messages into the ether. Happiness in my own company is something I never thought I would truly possess, and I desire longer swathes of golden ticket time alone to release my thrashing kite string. I am energised by visits and familiar faces. It is increasingly apparent too that I can only move forward now with purpose by acknowledging much of what has gone before me – tracing the gullies and the examining the strata. With a friend’s thoughtful encouragement, I book a week’s writing break next spring at Moniack Mhor, and a train ride to friends in Kirkcudbright, the family graves in Creetown and the standing stones at Cairn Holy. This will be the first time I have left my eldest child for more than two days in the 14 years since she was born – fear of something happening and not being around has always proved way too unwieldy. I have decided that looping back is essential for where I am going internally: where people, memory and place meld and shape shift. I want to re-cut the grooves. I recall a frantic dream where someone that once loomed large life my life towered over me as I dug the earth with my hands, water rising stealthily around me and his spartan tones informing me “only when you have found the bones will you know what passed between us”. It still turns quietly somewhere inside me.

In mid-November I walk up the field where a neighbour has been cutting his bulk of winter logs and the sun is starting to create lilac hues as it flirts with the top of a row of pines. He and I have struck up an easy friendship this past year, and he smiles whilst holding his rollie pinched hard between forefinger and thumb, partly concealed in his palm – a habit perhaps from childhood and rolled by the same hands that can build and shape almost anything. He tells me he has seen a Barn Owl flitting around as he works, so I walk down to the bottom field, and from nowhere it emerges towards me, almost unaware of me until it is overhead then circling back suddenly to the trees. It’s 3pm and I am surprised it is so visible in daylight, either safe here in the hills, or more worryingly perhaps hunger has driven it out at less auspicious hours. I feel like I can’t breathe, such is the potent feeling of hearing its wings pulse overhead, and turn back to tell him. One neighbour tells me some days later it flies alongside them when he walks his dogs down to the fast-coursing river at Bickham at dusk. Another tells me that he sees it peering at him from the barn he keeps his sheep in. Another hears it in the quarry behind our houses. It feels incredibly trusting to allow such a close distance to us unpredictable two-legged mammals. As the weeks wear on it edges closer each day and sits on my daughter’s swing ten feet or so away, cocking its head to one side as I stand at the gate – trust is slowly being built. But by early December it’s gone. Though I traipse up the lane every day, it’s nowhere to be seen – but this gives me permission to leave the house and all that occupies me. I find a tiny arrow-shaped snowy feather under the swing, which I place carefully on my desk. I wonder how we are regarded by the life that observes us when so much of what we do is self-destructive or combative. Whether I think of growing up and the walks with my Dad through the sparse woodland flanking our council estate in Corby, the stress relieving bike rides of Tottenham Marshes close to the North Circular, or the hills of deepest Devon where I currently live, I feel no more or less connected to my surroundings — rather accepting what is absorbed into my blood and bone.

As liquid shadows dance on the wall, I sing to my sick daughter as she leans into me hard like a hiker in a blizzard. She watches my mouth intently as I sing the word “hello” from a rhyme she used to love sung to her at school to start the day, and I see her tongue moving to the front of her teeth to mimic mine. My brain fizzes and spits with recognition. I spend my life interpreting her needs and desires and I am not always right, especially of late. We visit my neighbour, who is sick, in her garden, and my daughter holds her wrists, looking into her face full beam and enquiring when I merely take soup, more inclined to circumnavigate the subject of her illness for fear of creating unnecessary discomfort. I should know better. Another day she takes the hand of my aforementioned wood cutting neighbour who is chatting to me on the front doorstep, a drill slung over his forearm like a poacher’s catch. She moves me sharply aside, wobbles as she links his arm, and walks him around the house, up the steps to the back door, which is stuck and broken. He smiles at her and asks if she wants him to mend it and she taps his wiry arm in affirmation – this door she can manage almost independently whereas the other one is steeper and unsettles her balance due to no depth of field. As he takes the door off its hinges a day later my daughter dances and claps, exhilarated that she has been heard. Tears stipple my eyes. Despite her vulnerability, she has always, in her own fashion, communicated and used intuition despite all that confines her. She is also untouched by the social media grids that now underpin our inter-connection, work, evidence our daily goings-on, or clamour for attention. She is entirely free and is a gentle flame on murkier days, willing me on.

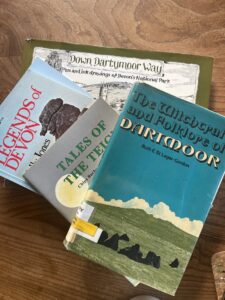

Every weekend in the pouches of time that shared parenting permits, I learn more about the ghosts in the landscape. I collect small press books on Dartmoor from charity shops nearby, online, and some are gifted by friends. As I read I am aware that many of these places are still abstract and I can’t pin emotions to them, unlike each road in the new town I grew up in, familiar and weighted with memory — the old original Corby village one side and chocolate box cottages of Rockingham, all the estates, factories, and the once booming steelworks sandwiched between like an overstuffed pillowcase, with wide roads and prefab streets that still stand today. I feel somewhat nostalgic toward the back-room pub “alternative night” of the “Rock” where local teenage bands would play, and we were emboldened by whatever cheap booze we had brought in, secreted in an inside jacket pocket and tipped less than subtly into glasses under dimly lit tables. I think of John Burnside perfectly encapsulating the last moments of the dancefloor before the lights go up in ‘I Put A Spell On You’ – and how one person can suddenly become “beglamoured” by liquor, attention or stars aligning in the dying embers of the evening, and it not always ending well. I also recall the drunks from the other side of the pub gathering outside for kicks, picking fights as they leered and swaggered and we ran giddy in our small, weird tribes; under streetlights, trying to hail cabs.

When in London I jammed in as much as I could, ricocheting from gigs, to galleries, to pubs and parties like a spiky flow chart across the city. Here in Devon I am drawn hard by the stealthy pull of moors and the sea – it is up to me now to create my own marks. I go to the excellent Dartington Bookshop in Totnes to a rich talk by Ethan Pennell, and hear folklore stories of witches shapeshifting into hares, standing stones and wraithlike hounds that disarm travellers, and I glean more still from the books that litter my kitchen table. A trip in a fine haar to Scorhill Stones near Gidleigh bewitches me profoundly and leaves a long shadow. I think of women in centuries passed brought to this place to repent for pleasures of the flesh, and how despite reams of years since, we never truly learnt much at all.

To mark the encroaching end of the year I visit Totnes market — a place that bookends my week. I get up early to pace around its stalls. After a year I know many of the traders to comfortably have a bit of banter with, and energy is high today. By chance, I happen upon an installation at the Angel occasional space down a handsome side street, ducking away from the bustle of Christmas shoppers. As I walk into the building the installation is screened on an impressive old wooden Super 8 screen. Images flicker abstractly of performers dancing in and out of the sea in a surrealist manner, appearing to comment on relationships with the tide. In another short, a person concealed in a robot costume fashioned out of a large cardboard box walks further and further up a burnished moor in a strange meandering as a metaphor for creative learning outside of formal education. In the last short a swimmer skims close to the bottom of an old Victorian pool’s ceramic tiles, bubbles rising from their nose, and it’s so powerful sensorially I feel like the swimmer myself — a small group of us watch, transfixed. I chat to the artist Clare Dearnaly and she tells me, like me, she moved here a year ago and is just starting to make connections. We smile in recognition of starting again in terms of place and creativity and I leave wanting desperately to learn more about her work. Upstairs Sybille Pouzet’s rich atmospheric abstract watercolours pull me under the tow. I leave with an overwhelming certainty that I am in the right place.

As walk up one of the three beacons near South Brent to take in the long view, Laura Cannell and André Bosman’s New Christmas Rituals soar on my headphones, the wind rattles my bones, and my hair flies around like Leonora Carrington painted her own vertical electric locks – she understood very well the alchemic properties of hair. I can hear snatches of a small group chatting somewhere above me but can’t seem to catch sight of them. I avow to visit some stones on the forthcoming Winter Solstice to finally see if they align with the myriad constellations rather than the milky sun that liquefies over the surrounding peaks.

The south coast of Devon and parts of Cornwall are visible from this vantagepoint, an endless honeycombed chicken wire of fields, woodland patches, rivers and villages cascading, lava-like, with thousands of unknown lives burring and clicking inside. I break off some gorse, and pluck sheep’s wool from bracken for a wreath to dress the front door. I am ready to burn the small bundle of ash sticks that I have collected before old and new friends cross the threshold. I tighten my scarf as I walk back down the slope – making new ritual stitches in the seams of this place, and some too for those elsewhere.