Matthew Shaw finds deep time and hidden treasure just off the A35.

The A303 is known as the highway to the sun. In many ways it’s a problematic road, but one that offers a view of our most famous stone circle, Stonehenge. The glimpse the A303 offers of Stonehenge often brings the traffic to a halt and always slows cars down as people look across to the ancient stones as they pass.

However, there is another road and other stones, stones much less well known, that have captured my attention. A route that has opened connections through deep time for me, a landscape connection developed over the years.

The road is the A35 and it is a busy, fast and often dangerous arterial route across Dorset. It is a road that begins, or ends, depending on your direction of travel, between Southampton in Hampshire and Honiton in Devon. I am travelling east to west with Christchurch in Dorset as my starting point. As a result, I miss out on the beauty of the New Forest and it is not until I reach Bere Regis on the approach to Dorchester that my interest really kicks in and the road begins to reveal its true hidden treasures.

Tolpuddle is signposted as the next turnoff, and so I do turn off and go to pay respects to the working people who in the 1830s changed the world with their defiance against unjust pay and conditions. George Loveless, then 37 years old, along with five of his fellow workers, James Loveless, James Hammett, James Brine, Thomas Standfield and Thomas’s son John were charged with having taken an illegal oath to start a union to protest against their meagre pay of six shillings a week. The landowner and the local squire were not to take this union lightly and so the men were served with a warrant for their arrest and transported for seven years’ hard labour to Australia. A brutal and soul-destroying sentence but not one that would break George; indeed, it started a movement way beyond the initial gatherings of the small group of Tolpuddle Martyrs meeting beneath the village Sycamore tree. When word of the sentence travelled, the working class rose up, with an 800,000-strong petition delivered to Parliament as part of a massive demonstration that marched through the heart of London. In the centre of the village of Tolpuddle is now a sculpture to remember the martyrs, composed of a likeness of George with six upright stones behind him. Standing stones of defiance and fearlessness in the face of oppression. An ethical position set in stone.

My next stop is just a few miles along the road towards Higher Bockhampton and the cottage that was the birthplace of poet and author Thomas Hardy, preserved and protected in the style perhaps familiar to the young Thomas. The cottage still contains some of the magic that makes it possible for me to imagine the Hardys’ lives at that time. The way the sunlight falls today on the stairs allows me to daydream of Thomas as a boy, sat on the step, maybe daydreaming himself or reading in the warmth of the sunlight, perhaps the first seeds of future stories and poems planted in this very spot.

Just a little further along the A35 and I pull in again to Max Gate, the house designed and built by Hardy as a mature adult, a house utterly at the other end of the spectrum of Thomas Hardy’s life and work and fortune to the cottage in Higher Bockhampton. Here is grandeur and success but also sadness and loss. Between the two properties lies Thomas Hardy’s heart, or at least once would have, at St. Michael’s church in Stinsford. His heart remained in Dorset; the rest of his body interred in poets’ corner within Westminster Abbey. The contrast between Westminster and Stinsford is as stark and contrasted as the beginnings and ending of this Dorset poet’s life.

It is at this next point in my journey that my imagination is engaged with even deeper time. I spot two Bronze Age barrows on the brow of the hill at Winterborne Monkton and the gateway to this Dorset complex of ancient Britain opens up. Although technically I am still driving along the A35, I am now aware of the numinous pathways and trackways of ancient Britain opening up around me. To my left I catch a first glimpse of Maiden Castle, one of the largest and most complex hillforts in Europe. Time for another stop.

Maiden Castle spans thousands of years of life within its ramparts, from its time as a Neolithic enclosure from around 3500 BC to becoming a late Iron Age cemetery and later containing a Roman temple, built in the 4th century AD. It is to the Roman shrine that I head first. Two concentric squares mark out the footprint of the Romano-British temple. I walk within them, imagining the fusion of what then would have been a new Pagan religion based on native British and classical Roman beliefs becoming one new faith.

I walk along one of the ramparts, picturing the Iron Age roundhouses where there is now only grass and sheep. In the Iron Age this would have been a highly populated community full of industrious metalworking, textile production and grain harvesting and storage, a sustainable life for so many people.

As we travel back even further — 6000 years, to the Neolithic period — the industry would have been flint axes. This hill was cleared of ancient forest and the first mark of man was made in the form of a causewayed enclosure. I look across to Dorchester and the strange toytown-like complex of Poundbury, the architectural and social vision of our present King — a modern addition to Dorchester based on various eras of classical architecture that seems to be constantly swelling out into further housing and a continuation of human prescence in this ancient land. At Poundbury I pass through the last of the roundabouts that so confuse unfamiliar travellers with their last-minute addition of multiple lanes — a source of panic for so many drivers.

I drive down a steep incline and ahead is a much smaller country road. It is in a direct straight line ahead of me from this section of the A35, whereas the A35 itself is about to turn sharply to the left and continue its unbroken pace. The road ahead is marked on the map as Roman Road and I realise for the first time on this drive that I have been on the Roman Road for some time, changed and repurposed for more modern needs and increasing traffic to speed the route of those travelling the south coast. Beneath the tyres of our cars lie earlier foundations, stories, objects and lives lived, sped over, occluded with tarmac, cat’s eyes and white lines.

I enter the village of Winterbourne Abbas. Judging by the road conditions there must have been a lot of rain here recently; the surrounding hills and higher ground have led the rainfall to run down to the village and the ditch on the side of the road is almost overflowing. I pass picturesque cottages and the 13th century church and pull in near to the Coach and Horses, a 19th century coaching inn. From here I walk towards one of my favourite stone circles: The Nine Stones of Winterbourne Abbas.

In the late 1990s I moved from Cheshire to Dorset. I had grown to love Dorset from many trips to see friends and on moving realised it would be helpful to really understand where it was that I now lived – to gain a better understanding of how the towns and villages connected and to re-centre my world with this as my newly chosen home. The way in which I did this and the effect it has had on my life was unexpected and profound.

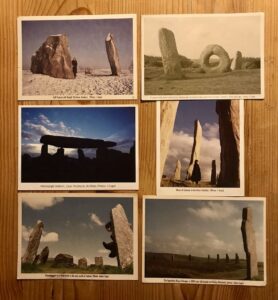

It all started with a postcard from Julian Cope, the songwriter and musician I listened to more than any other at this time. To be more precise it was a series of postcards, each of which intrigued me more. The postcards were all printed with the photograph of some ancient British site or other, and on the reverse was always a message from Julian about a forthcoming record or tour but more importantly to me now, they also included information about a book he was researching and writing about ancient British sites. The music Julian was making at this time was magical and increasingly included these ancient sites within the lyrics. This was clearly an awakening for Julian that directly awoke an interest in so many of us at this time. Julian is a master of making things exciting, whether ancient sites or unsung and obscure music from around the world. His highly anticipated book The Modern Antiquarian was finally published and very quickly an incredible, passionate community grew online around the accompanying website of the same name. The book was, and still is, essential. A book that changed my life. The community I became part of made me feel welcome. We would meet in real life away from our computers and the digital forums and in between these meet-ups share our stories of trips to sites through photographs, fieldnotes and folklore online. More than this the website also allowed us as users to add our own sites to the ever-increasing number of places to visit, swelling the number of sites to visit that Julian had gifted us in the book to hundreds more within a very short time — all of which we sought out and offered advice to each other on, things like which lay-bys to park in, how to get our hands on certain keys to unlock gates and dangerous cows to avoid.

On the 1st February 2004 I visited the Nine Stones of Winterbourne Abbas for the first time.

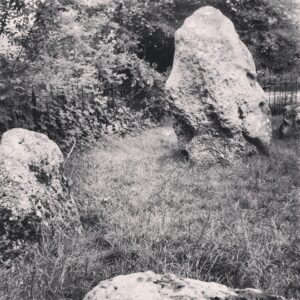

Stone circles are not particularly common in Dorset, or at least not many have survived. The Nine Stones is one of only four stone circles in Dorset today. A single stone lies just a short way away on the verge of the A35 by a ‘sharp bend’ warning sign. This stone is known as the Broadstone and could have been part of another stone circle, as mentioned in the 17th century by the antiquarian John Aubrey when he was surveying the area. There are other stones in the field nearby and perhaps others now beneath the surface of the road. Thankfully still intact though, or thereabouts, are The Nine Stones of Winterbourne Abbas, also known locally as the Devil’s Nine Stones or as The Nine Ladies. The circle dates from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age period. It is a small circle, around nine metres by eight meters in diameter. There is a wonderful illustration of the stones from 1724 by William Stukeley titled ‘A Celtic Temple at Winterburn’ that depicts the circle with what is now the A35 running past. The landscape illustrated is much more open than today, the circle more prominent, but it’s still instantly recognisable.

The folklore surrounding the stones include a story of how the stones are the Devil, his wife and their children, another story claiming the stones as children turned to stone for playing on the Sabbath and another about how no tree could ever grow within the circle itself. I’m less sure about the tree story as a very large beech tree grew on the perimeter until recently, when it became diseased and was chopped down. I was very upset when this happened as somehow it broke the spell between the circle and the speeding traffic of the A35. The leafy veil now gone, no longer enveloping and protecting the site. Since then, the roadside gate has been locked and a new hedge planted, which is maturing well and creating something of a barrier to the road once again. In a way I will be sad when the stones are no longer visible from the road: I wonder how many bored or daydreaming children might have spotted them from the side or back window of a car heading west on a day out or holiday. Perhaps these transient moments might have sparked their imagination with a glimpse that lasted only a second but would have remained for a lifetime. Still, what will be lost from view from the road will be present behind the hedge, and the access via the walk across the field from the village far preferable to the death-defying race across the road from the old layby.

For almost twenty years now this circle has been a part of my life and a place I return to repeatedly. If I haven’t time to stop, I still always look across and say hello in passing. I’ve spent many hours in all weather conditions and seasons here; visited in health and when perhaps needing a little boost to help me on my way. The stones always seem to respond. For me they represent a timeless knowledge and an intangible wisdom that is felt on entering the space but impossible to describe. I know so little about who created this monument or for what purpose, but do know that it’s an important place for me and I suspect it is for many others too. Perhaps this site has been somewhere special long before the stones were ever placed upright, it’s difficult to know, perhaps impossible to ever know. I do know though that there is the Winterbourne spring that emerges very close by and, like the relationship between Avebury and the Swallowhead spring, I feel that there is a connection here. Of course, practically, a fresh water source would have been valuable to our ancient ancestors — but there is something else of importance going on with this connection too I think: something elemental and lost in time to our modern way of seeing the world. Reluctantly I head back to the car and off I set again. I pass the Broadstone and continue on my way westwards.

Within less than a mile I am dissecting two halves of Winterbourne Poor Lot Barrows cemetery, which includes 44 Bronze Age barrows. If you want to see the variety of different round barrows from the Late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age then this is the ideal place to be. There are four main types to spot: Bowl Barrows which are steep-sided, Bell Barrows which have a small platform and narrow ditch surrounding the mound itself, Disc Barrows which have a wider ditch and are flatter, and Pond Barrows which are unusually hollow with a ditch surrounding them, as if depicting Saturn or a UFO impression. Rarely have I stopped the car and got out to investigate here, maybe only twice have I managed to find somewhere safe to pull in on a side road and venture up to the barrows themselves. Usually there is just a fleeting glimpse heading west with a wistful glance in the rear-view mirror. The journey back east always provides the better view from a distance from the perspective of being in a vehicle.

The last ancient site I pass on this stretch of road is the enormous Long Barrow on the brow of the next hill. Again, a difficult site to park up and walk to but a spectacular site to see nevertheless. From this point in the journey it would be easy to take a small detour to the now recumbent large stone circle at Kingston Russell, passing the Long Barrow known as the Grey Mare and her colts along the path or even to go a little further to see the very small Hampton Down stone circle and the Dolmen known as The Hellstone just a couple of fields away. Then there is the Valley of the Stones, containing its glacial deposits and perhaps the location from which the stones for these stone circles originated, similarly to the more commonly made connection between Fyfield Down and Avebury in Wiltshire. All of these places are well worth a visit, all are incredible ancient sites, but they all reside just a little too far from the A35 for the purposes of today’s trip.

There is just one more place to visit today, and for that we have to head on to a place between Bridport and Lyme Regis, to somewhere known as The Cathedral of the Vale, or more commonly as The Church of St Candida and Holy Cross in Whitchurch Canonicorum.

This is the only place apart from Westminster Abbey with a surviving Medieval shrine containing the intact relics of its Saint. Indeed, the church may well owe its name to Saint Wite, Candida being the Latin form of white, perhaps also a reference to the light-coloured stone from which it is built. Locally St Wite is known as a Saxon holy woman who lived as a hermit on the cliffs. The church’s shrine is said to contain the relics of St Wite.

Pilgrims to the shrine believe these holy relics to have healing powers. The shrine contains three openings which enable visitors to place their personal belongings, or if they wish, to place their head or one of their limbs into the shrine. Today the openings are full with the many prayers left by people that have been here recently, this being a popular pilgrimage site to this day.

From martyrs to saints and the Neolithic to the present day, as the light fades my journey for today must end. I sit and listen to the birds roosting for the night in the churchyard and reflect on all of the generations of people that have called this land home. I think about the ancient pathways and the modern roads that overlay them, routes full of stories and the lives and journeys of so many people, past and present.