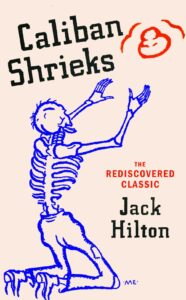

Originally published in 1936, Jack Hilton’s recently unearthed ‘Caliban Shrieks’ is an essential addition to the proletarian literary canon of the early 20th century, writes Adelle Stripe.

One of the most revealing aspects of Caliban Shrieks, Jack Hilton’s 1936 debut, is the pervading disdain for authority, whichever political persuasion that might be. Nobody is safe from his ire: Trade Unions, Conservatives, Liberals, Labour Party, Christians, police, prison workers, and even his fellow socialists. Part-polemic, part memoir, and mostly of the rhetorical persuasion, this raw and restless account of northern working-class life between the two world wars is told in a dizzying and often exhilarating prose style. Furious and enraged in many passages, and gleefully poetic in others, Hilton’s early work uses monologue, journalistic observations, and rich, descriptive reportage to dramatic effect. Unflinching, visceral, and candid in its desperate account of the everyday struggle of pitiful wages, he explores homelessness, military service and the ‘overcrowding, noise and revolting monotony’ of prison life.

Before Caliban’s publication, Hilton, a self-declared member of the ‘great unwashed’, had spent three years bound over after leading NUM agitation in Rochdale, where he worked as a doffer in a textile mill. As part of his sentence conditions, the author was prevented from speaking publicly, and spent this period writing short ‘state of the nation’ addresses, which were published by The Adelphi. These informal essays — which form the basis of the book — were written in a provocative style, using a frequently enraged vernacular, often with Shakespearean elements, hence the identification with Caliban from The Tempest, a character who was half human, half monster and enforced into slavery.

One of his keenest supporters was George Orwell, who described Hilton’s debut as being not a catalogue of facts, but instead “a vivid notion of what it feels like to be poor.” It is in the chapters describing the fear and anticipation of manhood, the misery of vagrancy and dosshouses, or the horror of trench life where the writing leans into a deeper literary mode. Recalling his memories of Flanders, Hilton writes of a brief moment of shelter and respite from gunfire: ‘There is, near enough to tread upon, the stiff cold forms of what was once two glowing breezy youths. So still and awry dead. The moon made their faces a bile-lit green.’

Using singular, plural and second person address, the ‘I’ is frequently erased, a technique borrowed from his background as a rabble-rousing speechwriter: skills which first brought trouble to his doorstep, and perhaps opened the door to his burgeoning literary career. Sympathy is not required from the reader; there is no self-pity about the situation. What is left, an indignant attitude about the incapability of those who rule, or the unending cycle of decline which the working-class faced, remains relevant in the 21st century. Ninety years after the book was first published, it continues to shine a light on the desperate situation faced by so many.

Post-WW2, the establishment figures who had once celebrated him (including Auden and Orwell, who he assisted with The Road to Wigan Pier), moved on to the latest literary trend, and although a series of books were published, writing failed to provide Hilton with a regular income. For him, economic security only existed through the plastering trade, and even with an education at Ruskin College that followed Caliban’s publication, the hardships of surviving as a working-class writer during this time proved impossible. He believed that literature was a bourgeois pursuit, one only possible for those who could afford it. Disillusionment had set in.

Unlike Walter Greenwood’s 1933 novel Love on the Dole, which is perhaps its closest geographical peer, Hilton’s work was not privy to adaptation, fame, and continued publication. Until recently, a first edition had been preserved at the Working Class Movement Library, where a visiting bartender, Jack Chadwick, pulled it from the shelf and was enlightened by the energy within its pages. His desire to see it republished resulted in a pursuit of Hilton’s friends and relatives through a poster campaign in local pubs. This new hardback edition features a smart preface revealing the story of how Caliban was found and revived, a tale which has appeared across the world in newspapers including the New York Times.

Although marketed as fiction, I would seriously question if this is a novel at all. Once compared by Stephen Spender to Louis Ferdinand Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night, Caliban shares some of the former’s spite, but little of its novelistic structure. It is, you could argue, more of a fictionalised autobiography. It contains flashes of brilliance, moments of tedium, and occasional optimism. By opening a window into a long-forgotten period into Lancashire’s pre-war industrial heritage, it is certainly an essential addition to the proletarian literary canon of the early 20th century.

*

The new Vintage Classics edition of ‘Caliban Shrieks’ is out now and available here (£16.14).