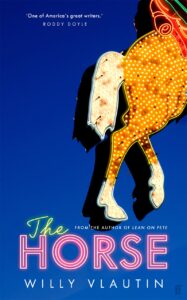

Willy Vlautin’s ‘The Horse’, soon to be published by Faber, is a triumph of hard, chiselled, beautiful language; of a great novelistic imagination and a huge heart, writes Will Burns.

Let’s assume that anybody reading this review of this book on this website needs no introduction to the double life of Willy Vlautin, the sometime author of deft and earthy fiction, sometime writer of deft and earthy songs. It might even be the case that you have found it surprising that Willy Vlautin has written so little in his fiction, directly at least, about that musical side of his life (I’m going to make the leap that you’ve read one or two or even more than that of his books as well) that such seemingly rich material, and such personally important material has eluded that meticulous and melancholy authorial eye of his. But how would one capture the strange thrill of writing a song? The intensity of hearing it played by exactly the right group of musicians in exactly the right moment — that otherworldly coalescence of timing, pitch and groove? Of knowing that song has had some profound effect on somebody else over a span of years and miles? In The Horse, Vlautin, who is after all perhaps uniquely positioned amongst contemporary American novelists to do so, communicates exactly that odd euphoria as well as its equivalent and inevitable disappointments and failures, its missteps and its miracles, with all his trademark soft-spoken genius.

That soft-spokenness is key here too — The Horse is a kind of underdog corollary to all those doorstop Great American Novels that seem to proclaim themselves as such even in their heft and certainly in their epic scope. Here the hero is Al Ward, by some measures an ‘unsuccessful’ late middle-aged songwriter and guitar player who has spent his life drinking and picking guitar in casinos and clubs and bars in bands of varying stripes and with varying degrees of material success — there are great nights, terrible nights, classic country covers, a handful of Al’s own originals sold and cut, there are the precipices of proper success, radio plays, money even, a period with a much younger pair of punk-country brothers who party as hard as they fight, but turn Al’s songs into something like the art he has somehow always desired for them. These various musical episodes are told through interspersed memory, narrated internally as Al moves through the present tense life of the novel — living alone on an abandoned mining lot and spending his days in a solitary kind of wilderness routine of fire-lighting, wood gathering and playing guitar. As the events of the novel unfold — with that quiet drama that Vlautin is so expert at — including the arrival of the titular horse, we are given much of Al’s previous life in flashbacks of recall and regret, allowing Vlautin to play with those Great American Novelistic themes with his unique sensibility. Here are all the foundational cultural touchstones of the place — alcohol, (American) music, family, sex, aspiration — and perhaps most importantly, the landscape of the American wilderness. For all the strength of Vlautin’s capacity for evoking the texture of Al’s musical life — you can practically smell the tequila and beer and short order cooking off the page — it’s the interplay between the urban American small city life of clubs, bars, diners and casinos, of main streets and pawn shop guitars, and the yearning Al has somehow always felt for wide outdoor spaces, and for a kind of innocence he seeks to regain, without ever being able to articulate it, in those spaces, which leads him with a particular kind of inevitability to the way of life in which we find him living at the start of the novel.

Al Ward’s life is Ahabian in the sense that he has devoted it — irrationally if not madly — to a single pursuit: that sensation, fleeting as it may be, of ‘relief’ (as Vlautin describes it) that comes with writing and finishing a song. But while that pursuit is located within the framework of the American wild, eventually in a kind of conflict with it, Al’s white whale is a more human construct than Ahab’s: the perfect song — or rather, and more simply, the next one. Vlautin’s is a kind of anti-epic, a more human, humble, and hopeful book that nonetheless posses all the stoicism and elemental Americana of its heftier forebears. It’s as heartbreaking as any great country song, but with that streak of weary resignation that, again, is a kind of antithesis to overblown notions like ‘defiance’. Al Ward is a sensitive, soulful man, who nonetheless, and like anyone else, is capable of ruinous mistakes.

Full disclosure time — I love all the bands that Willy Vlautin names as the spirit guides of his book, I love Willy’s bands, I love the shirt brands Willy names here, I love the tequilas Al drinks and the way he drinks them — what I’m saying is I may not be the most objective reader of this book, but nonetheless I’ll state it here as plainly as Vlautin himself might — this is a triumph of hard, chiselled, beautiful language, of a synthesis of aesthetic material, of a great novelistic imagination and a huge heart. To paraphrase Robert Lowell, let’s opt for the ‘grace of accuracy’ — I love Willy Vlautin.

*

‘The Horse’ is published next week. Buy a copy with signed bookplate here via the Heavenly Bandcamp page (£15.99).