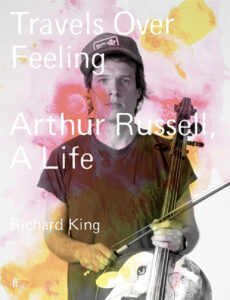

Newly published by Faber, Richard King’s ‘Travels Over Feeling’ builds a vivid, affectionate portrait of Arthur Russell through the ephemera of his creative life, writes Sally Rodgers.

When people talk about the composer, musician, singer and recording artist Arthur Russell, they often use the phrase ‘ahead of his time’. Reading Richard King’s new book, Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell, A Life, I was struck by the thought that Russell was in fact, emphatically ‘of’ and ‘in’ his own time. And that this sense of ‘presence’ was completely commensurate with his lifelong, somewhat free-wheeling Buddhist practice.

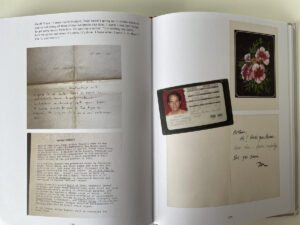

What is also striking about Russell is the pervading sense of his being possessed of a unique voice, one that ‘defies categorisation’. But in King’s book, which builds a vivid, affectionate portrait of this singular artist through the ephemera of his creative life — letters, flyers, record sleeves, concert programs — and the recollections of people who really knew him — friends, collaborators, fellow musicians, DJs — we see that his influences were many, just not all that obvious. A cult figure, beloved of obscurantists, Russell was himself exactly that, and by means of these carefully curated archive materials and oral testimonies, King unpacks yet more of those points of reference for us.

Like many American kids in the late 60s, he escaped the conservatism of his hometown (the wonderfully named Oskalooska in Iowa) to pursue his dreams of music-making in the acid fuelled creative chaos of San Francisco. As his sister Kate says, he had ‘no place to go but gone’. In an early letter to a school friend, he mentions he’s reading the poetry of Whitman and Ginsberg and seemingly within a short space of time he’s collaborating, and becoming firm friends with the famed author of ‘Howl’. While his contemporaries on Haight Ashbury are digging the Grateful Dead, Russell is wilfully immersed in the works of John Cage or the spiky contemporary classical of Morton Feldman. During time spent in Buddhist communes he develops his spiritual practice and that of the Indian and Hindustani raga and drone music that will manifest later in his own modular, generative approach to composition. A timetable of his studies at the Ali Akbar College of Music reveals his attendance at classes in free jazz, tabla, sitar and improvisation.

Russell’s move to New York in the early 70s, where he lived in Ginsberg’s apartment on East 10th street, is mapped in distinctive graphic scores for aleatory compositions, influenced by his studies at the Manhattan School of Music. There are images, letters and anecdotes that speak of Russell’s many collaborations — playing drums for Laurie Anderson or discussing his latest rule-based works with Christian Wolff. Hand-written flyers for performances encourage participation — ‘feel free to move around, come and go, talk’. King’s method of hanging back and letting the artists and literature talk, opens a lucid panorama of Russell’s immersion in New York’s New Music scene at a time of intense creativity. Russell’s tenure, at the age of 24, as musical director of the art-space The Kitchen is illustrated with program notes and press releases for video art, exhibitions and performances by Philip Glass, Alvin Lucier, The Modern Lovers and Steve Reich, alongside those of his own modal opus INSTRUMENTALS and side projects like The Flying Hearts and the Love of Life Orchestra.

Like his hand drawn artwork and silk-screened sleeves, Russell’s creative life was analogue. Working in an era when big studios were the only way to record, his endless hustle to find the funds to pay for expensive magnetic tape and studio time unfolds in notes, correspondence and booking slips. His baffled but loving parents loan him money. A&R legend John Hammond, whose signees include Dylan and Springsteen, pays for demos. Philip Glass recommends him to his Einstein on the Beach producer Robert Wilson, who commissions Russell to write a new opera, MEDEA. But Russell’s hard to contact (no phone), can’t meet deadlines and is not always the easiest guy to work with. Friend and collaborator Peter Gordon tells us ‘Someone could say to Arthur “We want something coloured red” [and] Arthur’d come in and explain why green is so much better…’.

By the mid 70s Russell’s was enjoying ‘weekend[s] of disco’ at clubs like The Gallery, Buttermilk Bottom, the Stud and Paradise Garage. Less interested in dancing than witnessing ‘the transformative energy of the beat played through a powerful sound system’, friends say he stood on the sidelines ‘studying humanity’. The looping, repetitive nature of minimal, serialist music, the improvisation of free-jazz, and his finely tuned rhythmic sensibilities are all evident in the disco classics ‘Go Bang’ and ‘Is it all Over My Face?’, made under the aliases Dinosaur L and Loose Joints. Musicians like Pete Zummo and Mustafa Khaliq Ahmed, who played on these records, suggest the sessions were loose, interchangeable — ‘a continuous experiment’. The masters were then handed over to DJs and producers like Larry Levan and François K to mix for the dancefloor, and his label partner in Sleeping Bag records, Will Socolov recounts bringing an acetate of ‘Go Bang’ to Mancuso at The Loft. As the place erupts in joyful appreciation Russell walks up to Socolov and says ‘we’re ruined. François has fucked up the EQ of the drums’. Anyone who works in electronic dance music will recognise familiar tropes. The ‘sharp practice’ of unscrupulous labels in the fast-turnover world of 12-inch singles; the endless quest for the perfect drum sound.

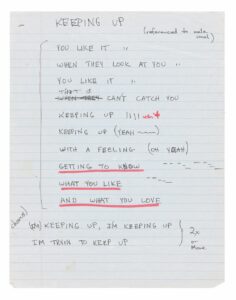

But while this perfectionism and paranoia resulted in the occasional falling out, failed projects would often be recycled into new works (some of his MEDEA experiments found their way into his TOWER OF MEANING release on Glass’s Chatham Square label). One casual performance at Phil Niblock’s loft space resulted in the WORLD OF ECHO recordings, which he further developed in work with the choreographer Alison Saltzinger. Songs like ‘This Is How We Walk on the Moon’ from the shelved album CORN, made in 1983, were revised and released on the ANOTHER THOUGHT album 10 years later.

The open-ended, iterative nature of his practice, and the affection of his friends and fellow artists, sings off the pages of Travels Over Feeling as King’s subtle interventions guide the narrative of Russell’s messy creative life, its non-sequiturs, and false starts. He reanimates the shabby, rent-controlled tenements and cultural conflations of New York’s East Village in the 70s and 80s, and uncovers some of the peculiarities that contributed to Russell’s fertile musical output — his love of bubble-gum pop, numerology, full moon recording sessions, boomboxes, fish tanks. The book also reveals that practically everyone who experienced his creative energy believed in his musical gifts. Against the grain of the prevailing Punk sound, vocalist Joyce Bowden describes his music as having a ‘feminine spirit’. The composer Jill Kroesen describes him as ‘always present.’

So, while his early death of an AIDs-related illness at the age of 42 is undoubtedly tragic, there is so much to celebrate within the materials King has gathered and shaped to form this rewarding addition to our understanding of Arthur Russell. In a music industry that (still) wants artists to do one thing, tour it and repeat, Russell’s confident, intuitive and bountiful creativity radiates from the music he left behind. As Peter Gordon puts it ‘…the action, the activity, that is the work’.

*

‘Travels Over Feeling’ is out now and available here.