Caught by the River spent 2023 sentencing writers and artists to time in a tower in a far corner of these islands. The third person to have served time in the Curfew Tower is Blue Kirkhope — whose stay was marked by boy racers, eggshells on the mantelpiece, and swallows through the window.

The Curfew Tower, Cushendall

When I think of “natural history”, I instantly picture poorly stuffed taxidermy in dust-filled museums, dead butterflies delicately pinned in an old picture frame, bugs imprisoned within the centre of a big chunk of resin, and my old battered copy of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin — purchased from a charity shop in Pitlochry in my early twenties, in an attempt to better understand the world and my own place within it.

When I was sentenced to serve time in the Curfew Tower last summer by the kind folks at Caught by the River on behalf of Bill Drummond, to write about the natural history of Cushendall, I did not know much about what I wanted to write. But what I did know was that I didn’t want to come to Cushendall as an outsider and tell the story of its nature or its history on the community’s behalf — but rather for them to tell this story, and for me to learn about all of these things through the very people and generations who have graced the high street, the sand and pebbled beach, along the River Dall and through the glens for many years before my arrival as a stranger across the Irish sea. When I first began writing about nature, I romanticised wide open spaces, continuously dreamed of solitude and sought after emptiness as a means of seeking fulfilment. But I came to learn that it is far less enriching to experience nature in this way, and now I seek the company of others to learn about a place. It is with this all in mind that my contribution to The Natural History of Cushendall will be a series of essays centred around several members of the community, alongside a black-and-white portrait of each person, whilst this blog piece will shed a little light on my own experience there.

I arrived in Cushendall on a warm Friday in June last year, and the summer heat was sticking to my skin. The town is nestled within the Glens of Antrim, situated on the north-east coast of Northern Ireland. I chose to travel over from Glasgow by ferry, from Cairnryan to Belfast, not only because it is better for the environment, but also because the journey across the sea seemed like an important part of the experience for me. Despite never stepping foot there previously, I have often seen the blue haze of its blurred edges whilst standing on beaches in Ayrshire on the west coast of Scotland, and throughout human existence there is nothing more alluring than a piece of land across the sea, out of reach, beckoning you.

The Antrim Hills shrouded by clouds and the small headland known as Drumadried or, locally, The Dog’s Nose

Zippy, custodian of the Curfew Tower keys, immediately arrived into my life like a firework; disarming my Scottish humour with his Irish wit. After showing me around and up and down the five floors of the tower, I chose to settle in the first bedroom on the fourth floor, only slightly lowering the risk of falling down one of the flights of narrow stairs in the middle of the night. Johnny Joe’s, I was told, was the place to go, and on Friday evenings there was live music there. Notebook in hand, I made my way to the pub and nestled into a corner with a pint of Guinness, which ended up being several, quickly and comfortably sinking into being away from home where my life was falling apart at the seams.

When I woke up in the tower the following morning, a swallow flew into the bedroom through the sash window. Swallows supposedly symbolise good luck and positive change, so this was a welcome sign during a time of need. I opened the two other windows in the room and used my body and limbs to navigate it back out towards the sky. The swallows were nesting in the derelict house just next door and they kept me company during hot sunny days in the garden.

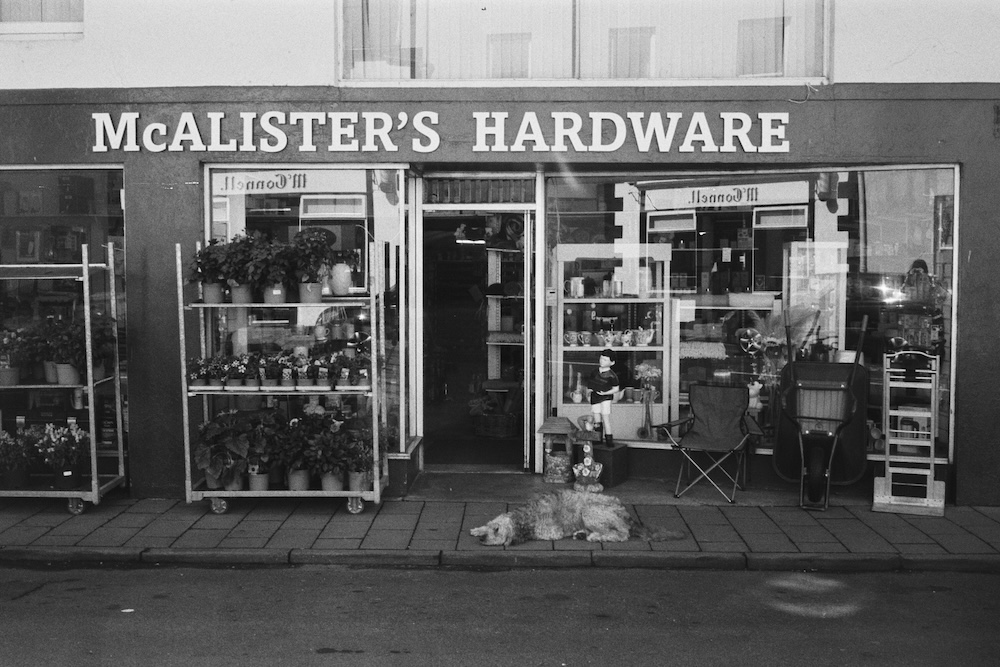

I spent many days in the garden of the Curfew Tower; a little heavenly suntrap where my robin and thrush friends came to visit every day as the swallows flew overhead. The setting of the tower had a particular song to me, featuring the doorbell from McAlister’s Hardware store frequently dinging as customers went in and out, house sparrows cheeping, swallows warbling, seagulls singing, the road traffic humming, the Friday and Saturday night crowds spilling into the streets from the pubs in the early hours on a quest for greasy chips, and the boy racers doing their weekend rounds of donuts, the traces of black tyre marks found in the streets the following mornings.

McAlister’s Hardware store on Shore St, Cushendall

After a few days of exploration and introductions, I headed to Cushendall Library on, by sheer coincidence, its 40th birthday, where I fumbled through its archives and its history, of which there was a lot. But being tucked away in the library in isolation wasn’t what I was there for, so I decided to print ten posters to display around the town, inviting the local people to take me on their favourite nature walks, whatever they deemed as “nature”. Quite quickly my diary began to fill with all kinds of walks with different people, most of whom I either met in the pub or was introduced to by the inimitable Zippy or dearest Feargal – another Cushendall resident who made my trip incredibly special. Throughout my two and a half weeks there, I was taken to a medieval cemetery, for walks along the cliffs and the coast, through tall grass, up hills and across fields with members of the community who had a deep and special connection to these places.

Climate change was also an important aspect for me to acknowledge throughout my discussions with the various people of Cushendall. I asked everyone to look through the lens of climate change — otherwise you wouldn’t get a real sense of nature at all. They told me how the landscape had changed over time, of the coastal erosion of Cushendall beach, and that there are more dolphin sightings now — the dolphins shifting inwards, seeking food in shallower waters, because of the warming sea temperatures. Exciting for us as humans to see, but not so much for the creatures we shouldn’t have such close proximity to.

Cushendall is the anglicisation of Cois Abhann Dalla, meaning ‘foot of the river Dall’. Its natural landscapes are embedded within its name, throughout its history. Whilst it has shifted in some ways over time, the river still continues to flow from the hills to the sea, the ringed plovers still lay their eggs amongst the pebbles on the beach, and the clouds come and go, shrouding the Antrim Hills in the distance. Upon reluctantly departing the Curfew Tower and this special place, I left little pieces of my time in Cushendall on top of the fireplace in the living area of the third floor. There are fragments of swallow and wren eggs found in the garden, an array of sea glass, shells and pebbles gathered from my days spent at the beach. I usually fill my pockets with these gems and take them home with me as a way of gathering pieces of the places I have been and to remember them by. But this time, I left them behind, where they belong.

A ringed plover chick nestled amongst the pebbles on Cushendall beach

My time in Cushendall came when I needed it the very most. My life was on a cliff-edge, so to reside by the sea in Northern Ireland for a couple of weeks felt like a suitable way to try and haul myself away from its precipice, and to find my way back to myself again. Like the incident with the swallow in the Curfew Tower, the community of Cushendall guided me back out towards the sky, and I will always be grateful for my time there.

A gannet flying overhead from Cushendall beach

*

Blue Kirkhope is a writer from Glasgow, Scotland whose work focuses on community, the environment, climate change and nature connectedness. You can follow her on Instagram or subscribe to her Substack.