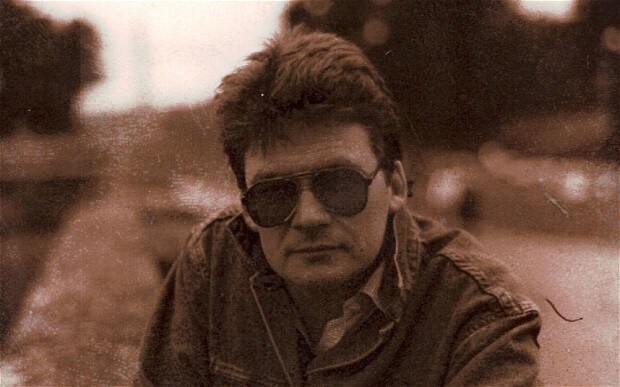

Kirsteen McNish pays tribute to her friend, the poet John Burnside, who died last week aged 69.

On Friday I learnt of the loss of a friend via a social media square, the words of a writer I follow on Instagram, beautifully simple and profound. Seconds later as I absorbed the news in disbelief, a friend who lives in Germany called, wanting to somehow cauterise the shock before I saw those words pixelated on my screen, moments too late.

Some seven years ago I met John at a reading at the LRB. He smiled at me and my friend, leaning in like plants towards the light with the excitement of hearing him talk, alongside Matthew Beaumont, on the subject of utopias. Whilst the host went through the preamble, John’s humour was evident and peppered his talk, despite the nature of some of the content and discussions around themes in his book Havergey; climate collapse, societal failure, human avarice and attempts at creating a new society in the mire of a collapsing planet. His energy remained high and vibrant throughout the event, and people queued in a long snake hoping for a chance to talk to him, each of us clutching this small book, published by Little Toller, in our grips. I stuttered out to him that I too grew up in Corby. I was the last in the line but I can’t remember what else I said — just that I wished I had something more intelligent to say.

I had come to John’s work a long time before – his first autobiography A Lie About My Father had been handed to me one Christmas, along with another book related to the industrial town I grew up in called Women Of Steel, written by a Corby playwright, Paula Boulton. The giver could not have known what he would spark in me with the gift of John’s work, and I fell quickly and deeply in love with it. It buried itself deep into my marrow, sang to me, thrilled me even, and the words seemed to have a life of their own, jumping around my head with each deftly hewn scene.His work has continued to rattle around my head since then, and it is often in my thoughts, like returning to a painting you love in the permanent collection of a gallery, seeing different things each time.

I had first made contact with John around a project that has long since passed, but we stayed in regular correspondence. I wrote my first piece about the loss of my sister on this website and he wrote to me shortly afterwards about it, about leaving the place where we both grew up, the natural world, overwhelm and also restraint. Since then, we would sometimes write to each other. I remember a few years ago sending him a download of Scott Barley’s hypnotic experimental film Sleep Has Her House and Laura Cannell’s ancient haunting music, both of which he loved, and after another interaction, a balm for muscle pain in the post — he sent me a parcel of books and links to music online he thought I might like in return. His choices of texts and music were always unexpected and often obscure (to me), and I learnt from him over and over without fail. Music, I feel, was always in his words, his rhythm and the pulse of his observations.

It didn’t matter in the end that we two didn’t end up working together collaboratively — our friendship would go on to outlast any project. But I still enjoyed the back and forth of compelling ideas alongside the exchange of flotsam and jetsam of daily life. The macro and micro is something John traversed with ease in all his work too. We spoke about fear, spirituality, ritual spaces and circular time, all of which will stay with me.

John was undoubtedly kind, but he wasn’t benign — he would readily look at the underbelly of life, at the horror and the gloaming, those that lack morality, the grotesque and the gruesome, seen most obviously in The Dumb House. He was also careful not to re-paint himself as the perfect protagonist in his biographies or poems where half-seen things, contradiction and murky thoughts, linger. He knew and wrote about failure, darkness, addiction, sexual pull, and losing his mind. He didn’t romanticise it either (which would have been easy to do), but rather showed the bleakness and futility that comes with the highs and the aftershock. There is an undercurrent in both his poetry and writing that warns about being wary of what you want, of greed and chasing desires as an impulse that can never really be sated. Satisfaction, he seems to convey, is in the waiting, the not-having, the commonplace and the minutiae, it’s in the now and it’s internal. ‘The Fair Chase’ in his Black Cat Bone collection illustrates this beautifully.

When lockdown had reached its zenith and things were loosening enough to go for walks outdoors, John suffered a serious heart attack which he somehow survived. On the day it happened I had seen a buzzard low over Epping Forest and had emailed him to tell him, marvelling at its sighting, which is a daily occurrence here in Devon now, but it was the first one there I had seen, hovering on the periphery of the forest. A week or two later he emailed me to say he had been gravely sick and had come back from this and written a poem, that he had seen things anew. Only he, I felt, could have come back from something as serious as that and had new, urgent work come forth, with renewed energy and hope rather than self pity or defeat. When I think of those slivers of exchanges it feels surreal and I am heartsick today, knowing there won’t be any more of his words, to me or on the page, and in awe at his capacity for generosity of time and thought for others whilst keeping up the level and volume of work and teaching and meaningful contact against a backdrop of chronic insomnia and ill health. Hilary Mantel was right when she said he was a master of language, but he was also a master of connection, of joining dots and creating complex and vibrant constellations.

Seemingly an element of modern friendships with distance bridged by the internet — and the logistical challenges of travel I face as a parent of a disabled child— I never visited John in Scotland, but I treasured this intermittent connection and his words, and when they came they were held close, and I took them with me everywhere. He sent me the following poem that had come to him shortly after I had sent him a photograph of a Swift as thunder was about to break. He could always see the spaces in between things, the opaque film between worlds, and make it golden:

Mid-afternoon, mid-summer, when it

darkens all at once, the traffic

suddenly illumined, daubs

of soft, electric gold

diffusing

in the petrol-tinted rain

till all the town becomes

a theatre, the play about to start

and what we had forgotten in ourselves

– the present tense, more urgent than we’d guessed –

resumes, as if we’d never gone astray.

There is so much to John’s life I don’t and couldn’t know about. It’s easy to think that because you have read someone’s work so closely, exchanged ideas, have listened, that you somehow know what makes them tick. When someone dies there are so many stories that bubble up, people offer up their interactions, and their personal take on that loss and it can be a comfort and brings many insights. John said he wasn’t afraid of death, (this Quietus interview reiterates that) but much of what I could tell he valued in this life was the art of listening as well as observing. He favoured absorbing things meaningfully rather than quick fixes — be it in art that he resisted being manipulated by, or by work that sets out to shock or emote rather than it soaking into you. To me, (in our interactions and in his published words), John always created spaces for the reader to step into, allowing the imagination to swell.

Certain qualities of light, and the sounds of birdsong amongst the combined buzz of the urban most of all, will always bring his work to me, and back home to my own childhood, the town we both grew up in. It also reminds me of the damage done to so many by poverty and lack of opportunity coupled with lack of infrastructure in neglected places — a quiet violence. In his work around Corby, John addressed violence (both parental and societal), the disappointment, the neglect, the imbalance and fear that lack of opportunity brings to so many — but he also saw the essence of people, the plight to just survive, forging bonds and that things can and do change, for good or bad. He didn’t shy away from politics, from religion, and anyone that listens to any of his radio interviews shows how determined his quest for honesty was; he was anti smoke-and-mirrors around the self, no room for neatness, epiphanies or self deception — one of the many things I loved about his work was that he didn’t try and manipulate, but lead you somewhere instead;

and, always, the sense

that something has still to appear,

some widow-maker, come in from the fields,

with nothing on its tongue

but lullaby.

In our last email exchange , I congratulated him on his much-deserved Cohen award, and we discussed confidence, coming through difficulties — he was candid and humble about his work and was touchingly encouraging with my own efforts. He spoke about the joy of his beloved grandson, and about seeing new directions after a long period of health struggles. On his sign off he urged me to keep moving forward. When things lit me up I often thought of him, and strangely with the onset of Spring each year and the sound of children playing and cars burring down estate roads, I thought of his writing about Corby, the then fire of the steelworks, the backroom bars and the pylons, and how much it has changed since we both lived there. I also thought about him when I saw flowers poking through concrete, or smelt the scent of bluebells in the woods — and survival against the odds.

I have found, today, an unsent email to him sitting quietly like a totemic stone in my drafts, entitled ‘Heron Days’ after one flew low over my head as I hung out washing in my garden. This auspicious creature was admired by us both greatly. He had once asked me what I thought it was trying to teach us in its watchful waiting. I hastily hammered out an email but never pressed send, being pulled in too many directions.

There are often things that sit within us, things that are not released, the loose ends and the thoughts that don’t get to manifest. These tiny losses, the whatshouldhavebeensaids can haunt the smudged edges of one’s psyche. John was so good at revealing the oft unsaid in all he wrote, writing the cracks, the disappearances, self destructive tendencies, the concealed, ignored, harboured, the hoped-for and the glimmers where we learn to rise up. We always think there are more tomorrows, we always think we have more time. But really there is never enough.

To be connected to someone whose work you admire and respect is a huge privilege, and there will be so many folk, like me, that John touched with his generosity and time. He was always considered in his responses, highly intelligent, and deeply reflective in our interactions and he didn’t have to interact at all really, but he did anyway, for which I am very grateful. I am aware too that there may be an imbalance with the weight in my connection to him compared to his connection to me, as he will, I am most certain, have been equally as generous to so many people who sought out his company, collaboration, and thoughts. What was fundamentally special was John himself, how much he seemed to give and especially what he opened up in his work with others, whatever that interaction might have been. I did often feel challenged and in awe, if not intimidated by his knowledge. He had a way of making you look again, re-consider, take out the ego, look at the core, and the places we commune for good or bad — and examine what lies beneath.

I woke early this morning with the tight chest that loss brings and walked up to the fields overlooking the valley, and stood there until there were no tears left to wring out, startling a pheasant whirring on a fence. I looked for signs that he was out there somewhere, alive in the dancing poplar trees, the solo Swallow looping above the grasses, the mist rising from the crease in the hills, and found nothing particular — and yet still he was of course, everywhere. His genuine affinity for the natural world was and will for me always be beyond comparison. This is not to say he was less talented at reading people; he painted their primal behaviours, vulnerabilities and qualities in incredible deft brushstrokes. He understood human nature better than most and yet did not seem to loftily judge — he illuminated it all instead.

There is so much truth in the adage that we never truly know what is around the corner and so today I keep re-reading his last sign off to me, like a circular tattoo inked into my skin. I hope his visceral, intricate seeing work in all its complexity is deservedly shared forever in universities, between friends, in libraries, online, in bookshops, and lives in people’s chests and under their skin. That other writers and poets speak his words out loud in absence of his voice. That those streams meet the rivers, and meet the sea. I am thinking of his family at the other end of the country that I have never met, and the loss of their brilliant, thoughtful, kaleidoscopic man. He will be greatly missed by so many, but his words will always endure, and the last ones he so generously sent to me in our last interchange I will hold on to:

There is always a test – but keep going … keep going – that is all there is to it.

*

John Burnside, 19 March 1955 – 29 May 2024