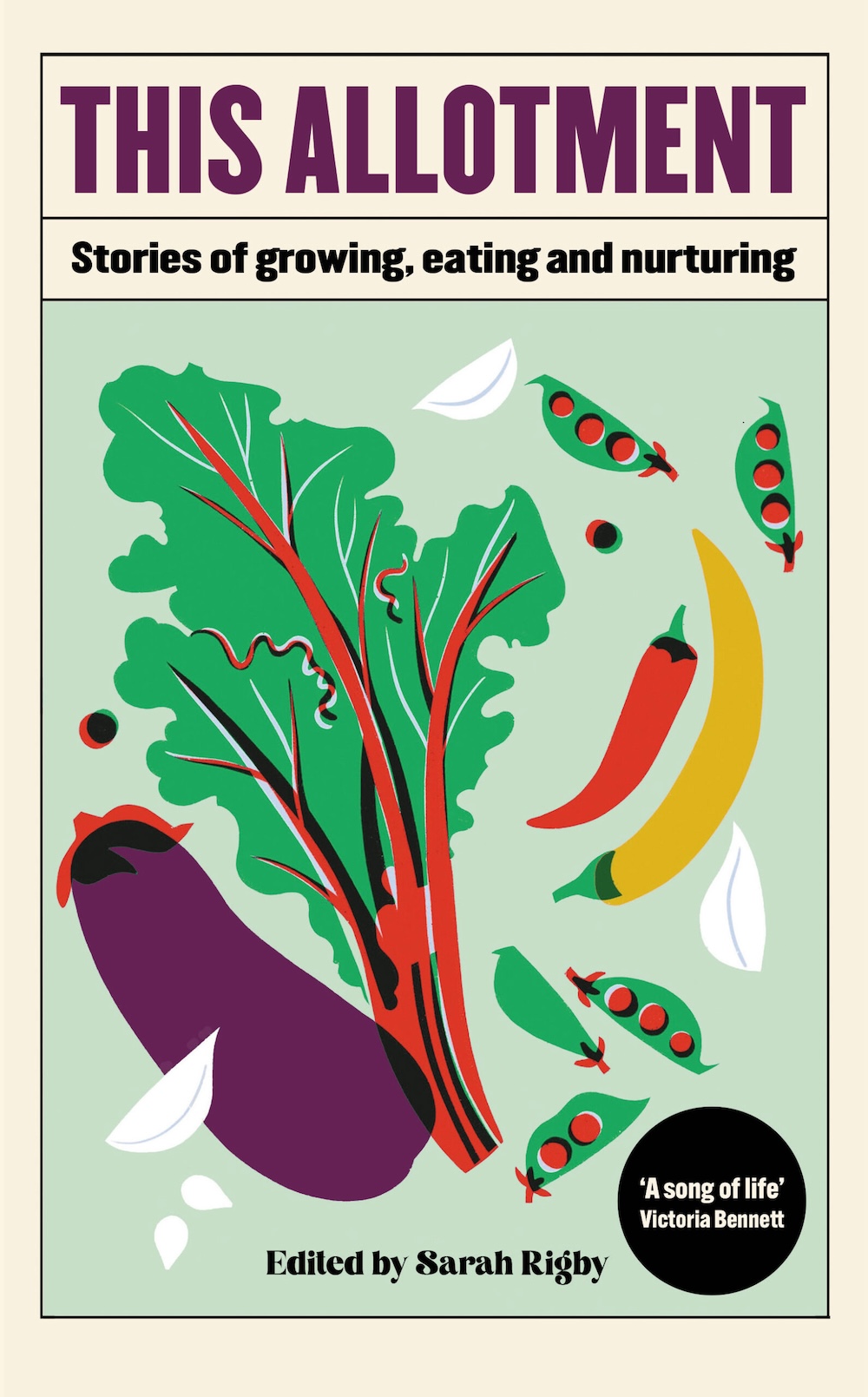

In an extract from ‘This Allotment: Stories of growing, eating and nurturing’, Jenny Chamarette considers intimacy with the land.

Our five-rod growing space lurches between industrious labour and temporary shambles. With each season I learn a little more about my mistakes and naiveties. The plot responds erratically and with unnerving regularity. This year’s ragged leeks mostly vanished with the early slug onslaught. Purple tatsoi are laced with a million tiny holes, courtesy of flea beetles. The shallow-bottomed celeriac have trailing root nests that are difficult to scrub clean for cooking. Bushels of celery are crowded with woodlice, who I gently discourage when I harvest the hearts. Perhaps if I’d pulled them sooner, if we’d blanched earlier, we’d have fewer terrestrial crustaceans. But I am not sure that would be a good thing.

A thick tangle of brambles runs along one edge of the plot. When clearing its edges earlier this year I noticed the decaying food trails of mice. Dropped roots, remnants of burst tomatoes and berry seeds led tiny paths through the thicket. Sometimes saying the obvious out loud is important. The plot was and is never ours exclusively.

The minor and inconsequential discoveries of our tenure beget strange companionship; small, intimate feelings. More than food or space, the plot breeds quietude. Acceptance of the botch, the flop, the fiasco. And also something focused and fascinated and diligent: not quite sexual, but a little like it. I would be lying if I said that there wasn’t some small erotic charge in the repetition of growth, glut and ruin, and my insistent attention to all three. There’s a feeling, generative and edgy, beyond what words can usefully express.

Here is what I know from knowing my plot. Food growing on an allotment is an act of mutual consent between humans, plants, climate and an unimaginably extensive range of soil-based life forms. In relationship to land I learn how I am always connected, even when I fumble. The land does not abandon me when I am inadequate to the task of caring for it. When I don’t have the language to describe these intimate, queer – yes, queer – feelings of land. Sexuality, love, joy, grief. Failure too, though that comes later.

There is wisdom in knowing land, in loving it. And it is a crime that this intimacy of land-knowing, land-loving, is not available to all. The most longstanding and brutal forms of human cruelty have all involved dispossession from land. Colonisation, occupation, enclosure, extraction and exploitation, war and its ecological devastations, mass pollution, land clearances and over-cultivation, forced migration, urbanisation: all sever people and beings from their roots in the land – or in the case of nomadic cultures, in the landscape, the weather, the earth’s spirit.

If intimacy with land were simple, then, as we hurtle towards our own destruction through biodiversity loss and climate crisis, exponential wealth inequality and chronic food insecurity, we humans wouldn’t feel so divided. Land disconnection is a first-world problem for sure, since colonial nations created it in the first place. Over the last four hundred years it has spread certainly and irrevocably across the globe, as successive waves of colonial power terminally disrupted countless indigenous land relationships, and then their own back home. I feel it too on the allotment, the pull of disconnection. I can’t pretend I don’t. But I am also learning, relearning, something much older than me.

Don’t misunderstand me: I still live a long way from ecological truth. Various unspoken powers uphold my land-growing and land-knowing. For example: the lease of an allotment is preceded by a number of small but crucial underlying elements. You have to know you will be living in one place for an extended period of time. The intention needs to be there, but also the possibility. This necessitates some degree of social and domestic security. The financial indemnity to maintain your home arrangements. In other words, you need to feel and be safe enough to persist, to remain. If I say that safety has been hard enough for me to come by, with all the structural advantages I have been afforded, what I mean to say is: it is not a guarantee. It takes a long time to forge a relationship with the land. Sometimes it doesn’t happen at all. Staying power is the power to stay. Only some of that is self-willed.

I also mean to say: land intimacy is a fundamental right, a fundamental responsibility. The confiscation and annexation of land divorces people from their most intimate relationship with earth. Land is neither to be owned nor requisitioned. It is to be grown. It is to be known, with many hands.

*

This piece by Jenny Chamarette is an extract from ‘This Allotment: Stories of Growing, Eating and Nurturing’ (Elliott & Thompson), out now in hardback and ebook. Read Ben Ewart Dean’s review here.

Jenny Chamarette is a queer non-binary writer, researcher, curator, artist and allotmenteer from south-east London who took on an allotment plot in autumn 2019, shortly before the outbreak of the Covid pandemic. Jenny has lived for many years with chronic illness and found writing and nature connection to be sources of truth in troubling times. ‘Q is for Garden’, Jenny’s nature memoir, was shortlisted for the Nature Chronicles biennial prize 2021/2, the Fitzcarraldo Essay Prize 2021, and longlisted for the Nan Shepherd Prize 2021. An extract from ‘Q is for Garden’ was published by Saraband in 2022. Elsewhere Jenny’s public words have appeared with MAI Journal, Another Gaze, Club des Femmes Culture Club, LUX, Litro Magazine, Sight & Sound and recently in an artist’s book by the queer art collective the Hildegard von Bingen Society for Gardening Companions.