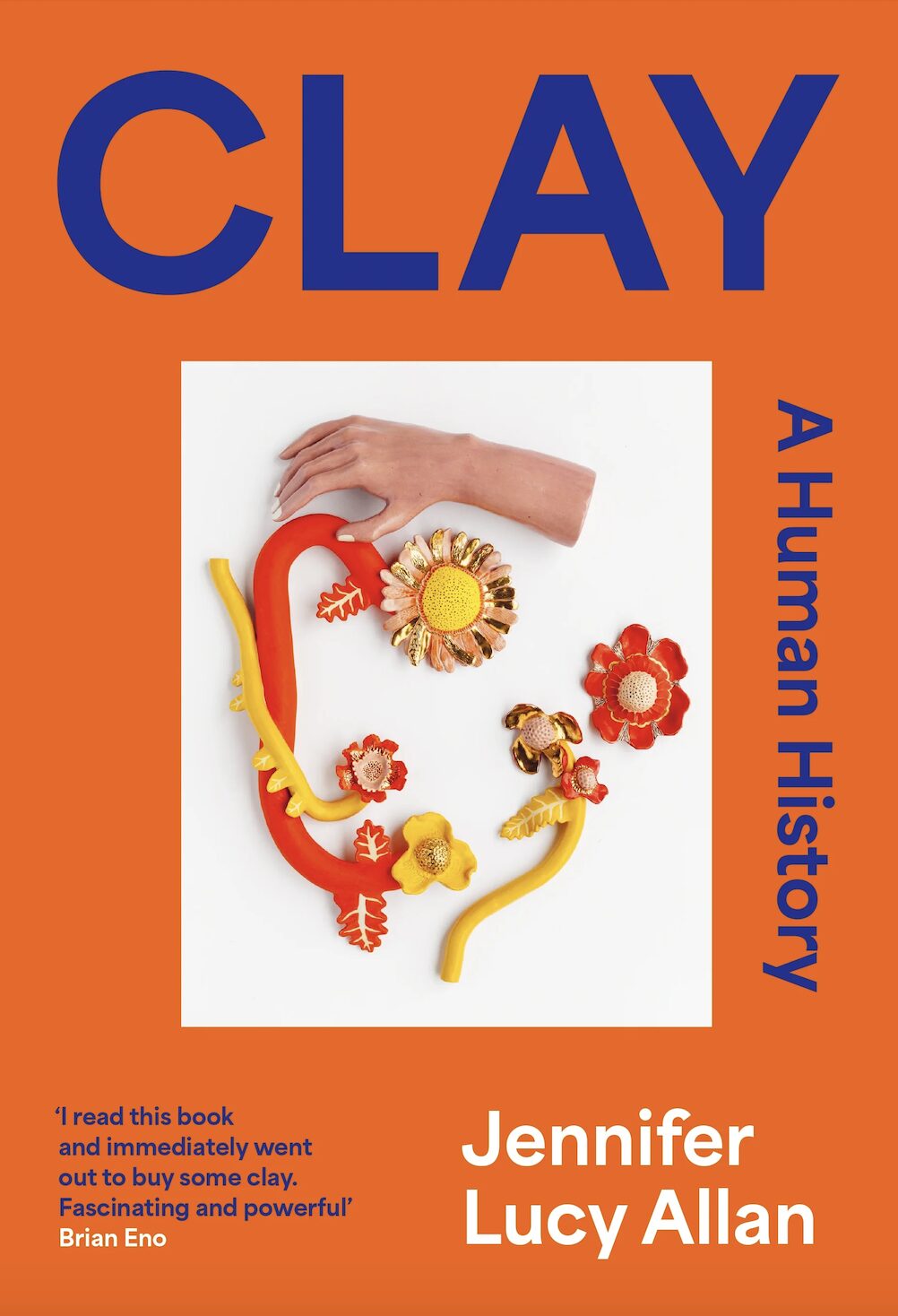

Published today by White Rabbit Books, Jennifer Lucy Allan’s ‘Clay: A Human History’ explores the profundity and wonder of clay, writes Annie Lord — and will inspire you to look upon your pots with new insight.

A few weeks before reading Jennifer Lucy Allan’s, Clay: A Human History, I taught a group of students how to make life-size clay heads. The heads were formed hollow, like a coil pot, and the features pushed out from the inside, rather than built up on the outer surface. Because of this, it often felt like the heads were appearing of their own accord, the hands of my students not controlling them, but guiding them into being. The night before I picked up Allan’s book, I dreamt I entered the classroom, and saw that overnight the heads had become more refined, more human-like. The lumps of clay were inching towards life; preparing to speak. Clay is a material which seeps into our consciousness. And no wonder when it holds so much transformative potential. Beginning as an amorphous substance, for millennia it has been shaped into vessels, sculptures, tiles, toilets and so much more. In Clay: A Human History, Allan sets out to explore the profundity and wonder of clay, investigating the role it plays in culture, technology, and domestic life.

Clay does not attempt to condense the magnitude and complexities of the history of ceramics into a single tome (such a thing would be impossible); instead we follow Allan’s diverse avenues of investigation. This book, Allan tells us, ‘…is one of sherds – of fragments assembled and inspected.’ It is split into 15 chapters exploring a particular theme. In Mud, Allan considers the role of clay in creation myths, later in Food, she investigates traditions of clay eating, and in Walls she reveals the fascinating history of ceramic houses.

Each chapter is richly researched, drawing on interviews with artists, makers, technicians as well as Allan’s own experience. Allan is a relative newcomer to the craft, having worked with clay for nine years. It is long enough to gain a deep understanding of the material, and the moments where she brings in her own embodied experience are particularly successful. Allan’s amateur status turns out to be one of the successes of the book. She brings in other voices to create a text which contains diverse experiences of clay, and in the process de-centres herself in the narrative. She does not ask, what can this material do for me? But instead, what can this material do? We hear first-hand from people who are pushing the possibilities of the material including Tyler Didier, who has developed a clay body inspired by the planet Mars and the artist Jade Montserrat, who makes performance pieces using clay.

Allan introduces us to several historic figures, bringing them to life through intensive research and fieldwork. I particularly appreciated the focus on Nirmala Patwardhan, who developed glazes used by Bernard Leach and other studio potters. Her work is vital to the success of these ceramics, yet her name is absent from them. Allan searches the archives for a piece of pottery decorated with one of Patwardhan’s glazes. It is an impossible task, and one that highlights the way that people can so easily be omitted in histories of ceramics.

A good book works its way into your brain – developing or enriching ideas in the mind of the reader. I have long been investigating ideas of permanence and impermanence in relation to art and writing and Clay teases out an interesting angle to this theme. I found myself writing excitable notes throughout the Words, chapter, in which Allan explores the importance of clay in relation to language and writing. She tells of ancient clay cuneiform tablets which were preserved when the library they were housed in was set on fire, the heat from the flames transforming the clay into long-lasting ceramics. Later, she introduces us to David Drake, a nineteenth-century enslaved potter, who carved inscriptions into his own pots, creating a legacy that recorded not only his handwriting, but his voice and intonations.

In a book which explores so many aspects, there will inevitably be chapters which captivate individual readers to a greater or lesser extent. I find Allan’s prose most striking when it draws from primary sources, and when she writes of the physical transformation of clay. At its best, Allan’s writing goes beyond the physical, revealing not only how we shape and adapt clay, but the profound meaning at the heart of it. Clay: A Human History, will inspire you to look upon your pots with new insight, and perhaps to dig into the earth, and lay your hands on this sticky, malleable, miraculous substance.

*

‘Clay: A Human History’ is out now and available here via our Bandcamp page (£19.00).

Annie Lord is an artist and writer based in Midlothian. In 2023 she was shortlisted for the Nan Shepherd nature writing prize for her work, ‘Morphoses: The Art of Nature’s Processes and Processed Nature’. She is currently the Connecting Threads artist in residence for the Lower Tweed, creating work inspired by Berwick Bridge. Follow her on Instagram / visit her website.