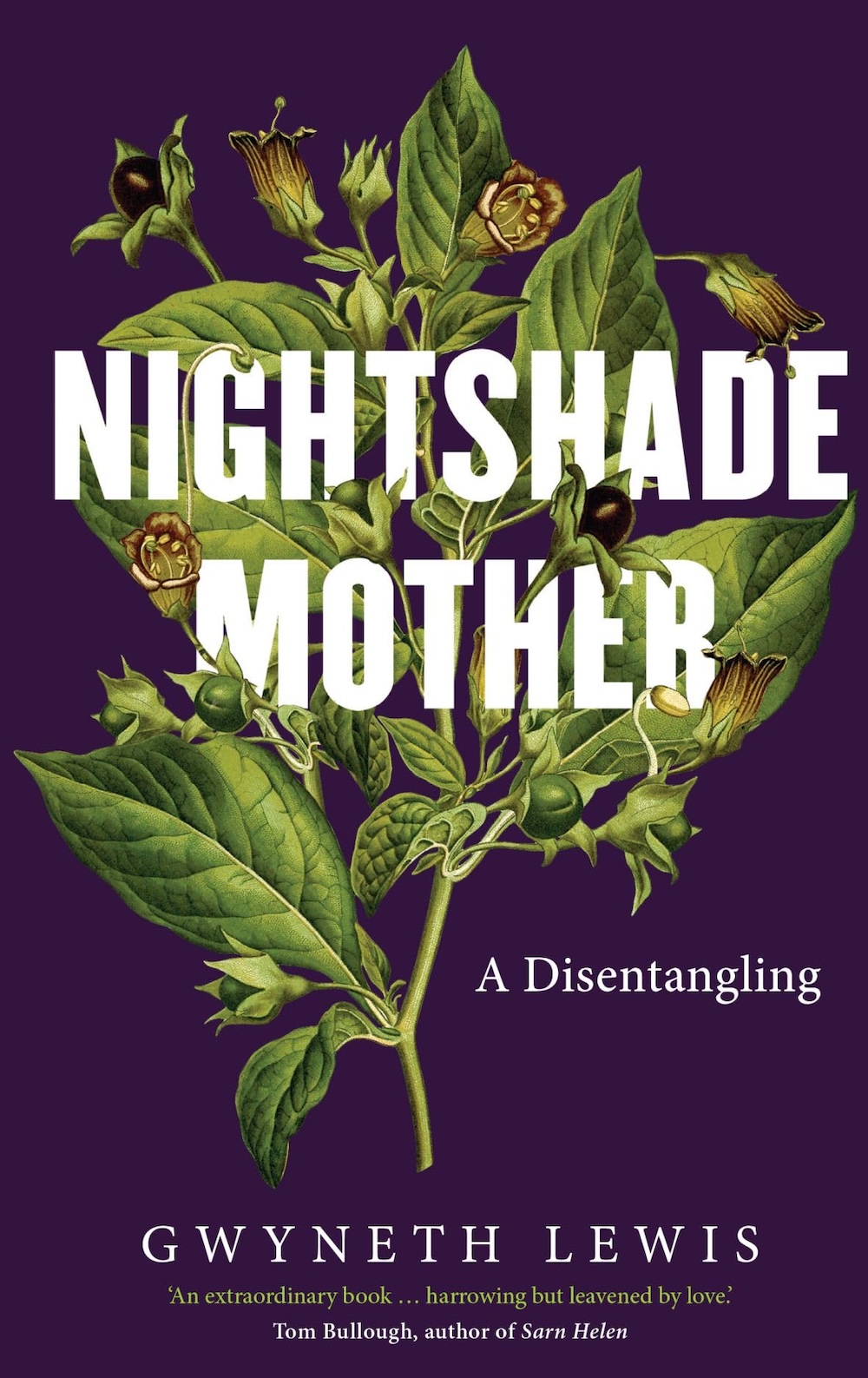

Interrogating a fraught relationship with an abusive parent, ‘Nightshade Mother: A Disentangling’ — the recently published memoir of Wales’ first National Poet Gwyneth Lewis — is beautiful, fierce, and wise, writes Pamela Petro.

It is always pure pleasure to read a book that crackles with intelligence, sparks of wit and insight flying like static electricity as you turn the pages. Nightshade Mother is just such a book — a memoir by Wales’ first National Poet, Gwyneth Lewis, which whets its clear-eyed prose on as rigorous an alliance of forthrightness and honesty as any of us is able to muster.

Lewis subtitles the work A Disentangling, which proves an acutely apt description. The disentangling at hand is that of her relationship with her mother, a task she likens to, ‘pulling a fishhook that’s become embedded in my eye.’ Lewis’s memoir is broken into two sections of multiple chapters each, ‘Toxins’, followed by ‘Antidotes’, both preceded by a Prelude in which she sets forth the great tangle of her life: growing up with a ‘nightshade mother’. Of the effects of maternal abuse, Lewis writes, ‘My mind perceives me as a trespasser in my own life’ — a perception that she admits lingers to this day.

Lewis’s narcissistic mother, Eryl, was verbally abusive and competitive, subconsciously conflating her eldest daughter with her sister (a parental favorite who decamped to America). Eryl was a serial over-stepper of boundaries, especially creative ones, in a way that fundamentally undermined Lewis’s trust in herself as a poet — a particularly crippling emotional injury, as from a young age it was in poetry that she sought selfhood and sanctuary.

Writing about a difficult parent comes with booby traps. Authors frequently come off as whiney, or, because the tale is lodged in their one-sided perspective, unfair to the parent. It is to her exceptional credit that Lewis avoids these traps. Determined not to treat anyone, even her mother, ‘irrationally and unfairly’, she takes an almost forensic approach to the ‘crime’ of Eryl’s parenting, sifting primary source documents for a multitude of voices — particularly her youthful journals, which reveal her own childhood voice, as well as family letters and photos, which she ‘reads’ with eyes keenly peeled for visual clues — questioning her conclusions through a running debate in italics that winds through the book. (The part of devil’s advocate in the debate is voiced by a favorite childhood toy, a monkey puppet appropriately named, in Welsh, Mwnci). Here is one of their exchanges, as Lewis questions her right to pen a memoir indicting her mother—a tale she calls, memorably, a ‘de-forgiving’ —

But how dare I?

That’s Eryl’s voice in your head. Ignore it.

What if I’m committing a terrible injustice?

You’re not. Just write this well and all will come good.

These exchanges amplify what Lewis calls ‘the double moral vision about myself that gives me emotional vertigo to this day’, a split-screen, inner contradiction resulting from Eryl’s unpredictable rage, which leads to an inability to trust her own judgement. She gives the example of accidentally breaking a bottle of milk on the porch step as a child. Panic stricken, she tries to beg a new bottle off friends, but no one helps.

‘Eryl’s fury’, writes Lewis, ‘goes from nought to sixty in a second…’ as she refuses to ‘recognize the idea of an accident.’ Told to “Get out of my sight,” Lewis hides in her bedroom, though Eryl follows her to berate her again, ‘like a dog tearing at a carcass.’

‘If your mother tells you often during your early childhood that you’re wicked, you believe her. But another part of me also knows that this treatment’s unjust. My opinion of myself splits in two.”

True to her word, Lewis balances her mother’s cruelty with examples of both mercurial and endemic kindnesses. An admission late in life to Lewis’s husband, Leighton, that he is “nearly wonderful” — a great surprise, as Eryl long regarded him as an enemy (he calls her “feral Eryl”); an abundance of homemade dresses and cakes in Lewis’s youth. These different tonal notes play across chapters fractured into short, stanza-like segments that beautifully betray a poet’s ear for rhythm and practice of seeking insight through metaphor. Lewis’s striking language further evokes her poetry: her grandmother’s body, accidentally glimpsed in the bath, ‘looked as if it were made out of melting butter’; she dubs a preacher’s predictable sermon an ’emotional wash cycle’. This latter example should reassure potential readers that while Lewis’s memoir is no happy sashay down memory lane, she employs a mordant wit and perspective on her subject that consistently brightens and refreshes the material.

For all the evidence Lewis summons against her mother — a small instance stuck with me: Eryl’s joy at Lewis’ arrival vanishes when she realises that Lewis isn’t her sister — the saddest and most persistent evidence of damage done is Lewis’s subtle shifting from past into present tense throughout this beautiful, fierce, wise memoir, as if to say, the past persists; the pain, while understood, endures.

*

‘Nightshade Mother’ is out now and available here, published by University of Wales Press (£18.04).

Pamela Petro’s most recent book, ‘The Long Field – Wales and the Presence of Absence, a Memoir’ (Little Toller, 2021), was a travel book of the year by The Financial Times and The Sunday Telegraph.