In 2024, Annie Lord met, and marvelled at, Frank Auerbach’s Charcoal Heads.

Throughout the 1950s and into the early 60s, the artist Frank Auerbach (1931 – 2024) worked on a series of portraits using charcoal and chalk on paper. He saw the Charcoal Heads series not as preliminary sketches but fully formed artworks. He nearly always chose to draw people who were familiar to him: good friends, relatives, his wife, and would work on a single drawing for months on end, building up layers of charcoal, erasing them, then starting again. Often, he would work the paper so hard it would tear and break. But instead of seeing this as a sign to stop, he simply patched it up with another piece, and carried on. For years I have looked at these images in books and online. I love the way he approaches charcoal as a sculptural medium, pushing and pulling it across the page as though he were working with a lump of clay. But it was not until May of 2024 that I got the chance to see them in person, travelling to London to see an exhibition of the Charcoal Heads at the Courtauld Gallery. Walking into the gallery, I feel as though I am meeting a set of familiar faces. But having only seen these artworks in reproductions, I am surprised by their scale. The heads are generously drawn, a little bigger than life-size and each of them rests within monochrome space.

When I first see her, I perceive her at rest. This, the label says, is the Head of E.O.W, completed in 1957. Like many of Auerbach’s portraits, the figure tilts her head to one side, her eyes cast downwards. While I’m standing in front of the drawing, two other visitors come up behind me and start discussing the fact that the pose is that of the Madonna. They’re right; this gesture recalls hundreds of years of Christian iconography. I begin to sketch Auerbach’s drawing, wanting to absorb some of his movements into my body. My wrist arcs back and forth as I draw her hair – a halo, made not of gold but of carbon black. Conscious of not wanting to block sight of her for too long, I move on, visiting each of the other drawings in turn. I feel as though I must do justice to each of these pieces, but already I am flagging. The gentle ache behind my eyeball is slowly but steadily developing into a migraine.

Before I leave, I return to her. But surely, I am mistaken. This is not the same figure. Gone is her peaceful reverence. Instead, I see that her face has been drawn on paper that is patched in multiple places, the torn edges creating breaks in her skin. She looks tired and worn. Her mouth turns down at the corners, and her eyes are cast in deep shadow. I check the title I have written in my notebook, and the photo I took minutes earlier, just to ensure that this is the same artwork. And it is.

It is as though Auerbach’s tendency to remake and reconfigure his drawings continues long after he puts down his charcoal and decides he is done. They shift and transform, refusing to stay still, even now that they are contained behind glass. Standing in front of these pictures, the border between viewer and artwork feels permeable. We cannot help but impress ourselves on them, and them on us. I go to look at another drawing, and just as I am admiring the light that falls upon the face, I hear someone behind me mutter agony.

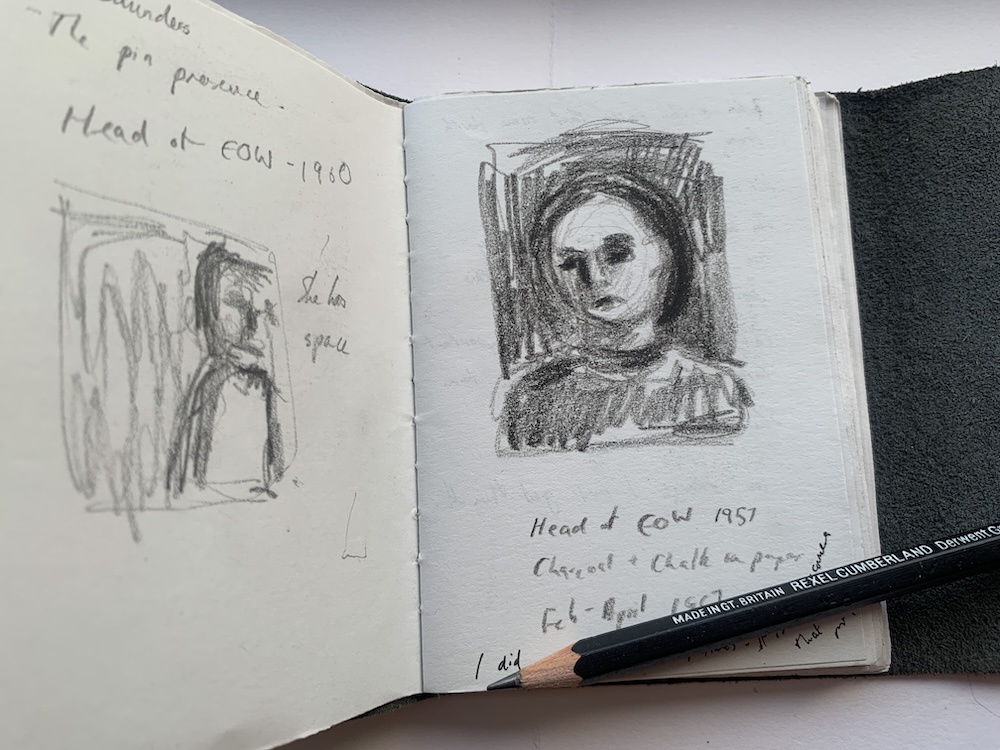

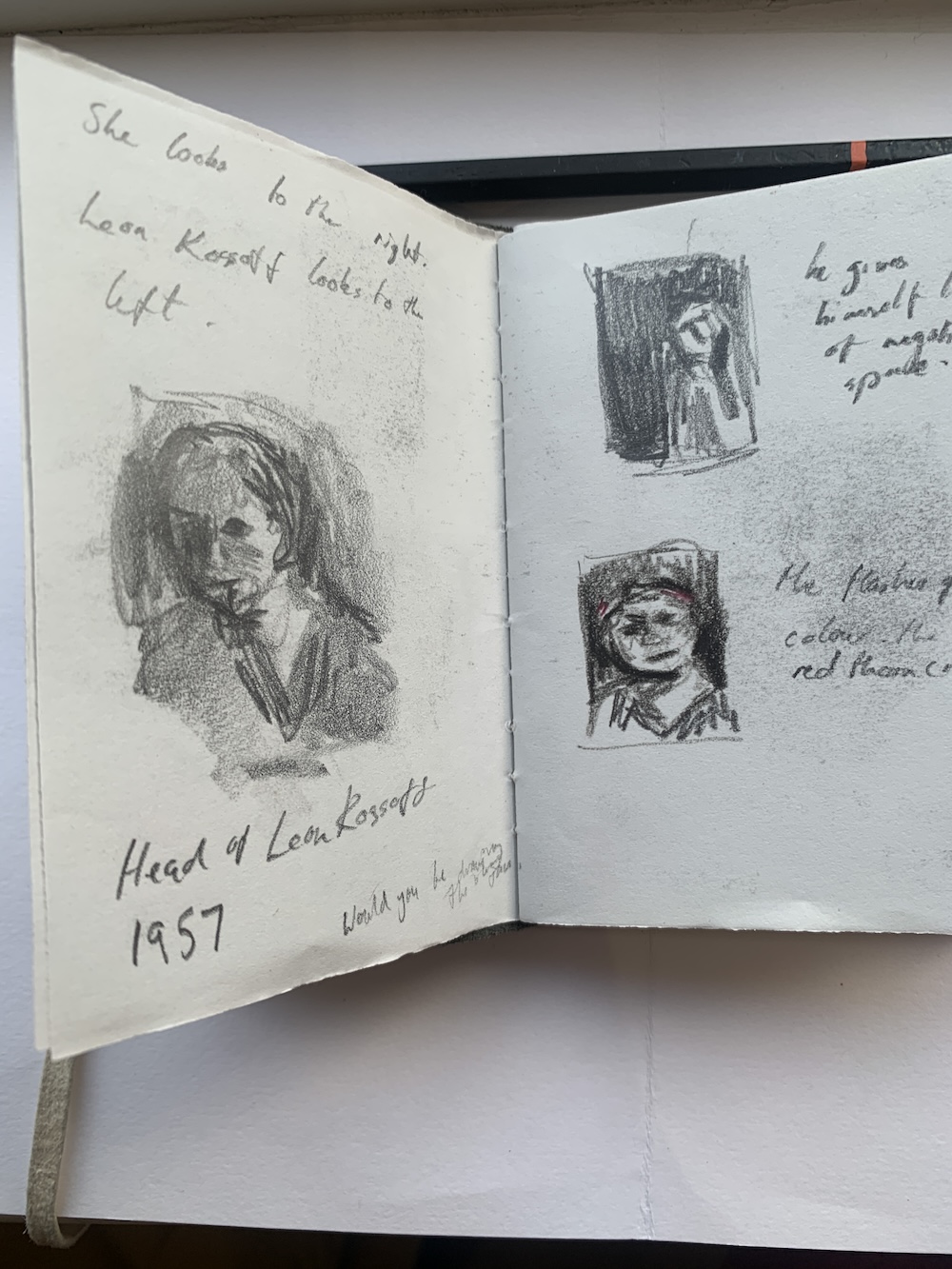

Afterwards, a friend who’d been with me asked me why I’d chosen to stand in front of these pictures and not just look at them, but draw them. I told him that it was a chance to slow down and that it helped me understand them better. I wasn’t aiming for a facsimile – that would be a futile exercise. After all, there I was, with my palm-sized notebook and neat graphite pencil, facing up to Auerbach’s bigger than life-sized images, drawn with layer upon layer of soft, crumbling charcoal. So, I did the only thing I could and made miniatures of them, filling my pages with potent, passport-photo sized versions.

There was an element of greed in my gestures; I wanted to hold onto these images, to take something away from the exhibition. I did not trust my eyes and my brain to be the sole keepers. The Charcoal Heads are slippery. They shift and transform in response to each viewer, and with each viewing. Afterwards, I spoke to someone who found the images near unbearable. He saw such pain and suffering within them. I understood his position, and at the same time I saw something else. In those two gallery spaces I was surrounded by a room full of faces that reflected the multitudes of life, that flickered between different moods from one glance to the next. I saw my own mental state echoed back at me, realised how rapidly it fluctuated. A pinch of pain was enough to change everything I saw.

At the time of the exhibition, Frank Auerbach was 93, and still working, a fact that rumbled uncomfortably round the gallery spaces – he’s still alive you know. I don’t know why this took us all with such surprise. 93 is a good age, but not an impossible one. Auerbach died in November 2024. I have wondered whether the experience of being with the Charcoal Heads has changed because of his death. Have the images themselves become stilled? I suspect not. After all, it is us who keep them vibrant, by impressing our living selves upon them.

All of us have witnessed the face of a loved one change. A baby growing into adulthood, a parent ageing, a friend whose face shows their joy or worry or fatigue. We might have watched a face transform through illness, injury, medication, or the proximity of death. But though they can be utterly transformative, none of these changes negates what has gone before. When I look at Auerbach’s Charcoal Heads, I am struck by their refusal to obey a linear timeline. These faces flicker and spin in front of us. They are reborn upon each viewing. To some, these images have a deathly quality, but I cannot help but see them as relentlessly, persistently alive.