Throughout 2024, Tim Dee held daily meetings with a noisy green alien species.

My name is Tim; birds are still my bag, but now I need to declare a parakeet problem.

In January Tim moved home to England after five years in Cape Town. He today lives most of the time in southeast London with Jane. It’s a new life, all happily accommodated, except for the parakeets. For a seasoned birdman this is strange news – daily meetings in 2024 with the noisy green alien species have left him oddly scarred.

I count my chickens; I know eggs is eggs. The parakeets were the first species on my new birds-seen-from-the-house list; I was happy with that, but it and subsequent sightings have, as the year has gone on, also marked me with something like an ornithological trauma. I can hear squawks from the winter-stripped plane trees outside the window, they were the first sounds I heard on waking this morning, and they will be I know (already) the last birds I hear this solstical afternoon. We live cheek by jowl, the birds and me, but, despite many hundreds of encounters, I feel we are yet to meet properly as neighbours. We are not familiar, every sighting startles, leaving me avianly nonplussed. That’s another first. More than fifty years ago, when active with binoculars in London suburbs not dissimilar to SE24, I was easily identified as a bird-lover much enamoured of all our feathered friends. That i.d. was accurate then and has been for the years between but now, I find, across the same south London skies and down any number of its leafy streets, lives a conspicuous green and shouty bird that I seem unable (incapable? or reluctant?) to love.

Psittacula krameri, the ring-necked or rose-ringed parakeet, is the only naturalised parrot on the British list. A stuffed one tells part of the story of the 2024-2025 Natural History Museum special exhibit Birds: Brilliant and Bizarre. Widespread across the southern regions of the northern hemisphere of the old world, the species is native to dozens of countries from western Africa to Egypt and India and Pakistan to Burma and Nepal. Feral populations are established in many of the world’s cities and are especially common in Europe. The parakeets of south London are most likely the descendants of escaped pets who set up shop as would-be British birds from the 1950s onwards.

A raucous party of eight are busy in the tall plane outside the window. They aren’t bothered by me, but once again I have been surprised by them. They are shockers, these in-your-face bright-coloured loud-voiced parrots. And such self-confidant self-declaration resets the terms and conditions of our relationship every time we coincide. The new colours and new sounds, the new way they occupy the locale – they are green (very) and noisy (very) and here (now)…and you, you are nowt, just part of the background, monochromatic and workaday, subsidiary to the scene. I’ve never been so disconcerted, so triggered, so bewildered by a bird.

This year has been doubly strange because I thought I already knew the subject of concern.

In 2012, I made a BBC radio programme on the London parakeets and the contending explanations of their arrival onto the British scene. Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970), the props people responsible for The African Queen (1951), guerilla or lackadaisical aviculturalists (1950s–the present) – all these and more have been blamed. You can listen here. Having made that programme and recorded for it a roost of hundreds of parakeets at Esher rugby club, I began, ever the bird-nerd, to lecture BBC producer colleagues on the risk of inaccuracy in using new recordings of skyline audio-atmospheres as soundscapes for older stories. Drama directors knew not to include the banking roar of airliners in their atmos track behind an outdoor scene from a Jane Austen adaptation, but not many were alert to the cooing of collared doves which would have been first heard in Britain only in the 1950s, and now there were shrieking parakeets which would need to be wiped from any fresh recorded wildtrack that was earmarked for period use.

Then I left Britain and in the time of my South African sojourn something I want to call exponential or fissiparous has happened to the birds in London. Flying fast and directly over the head of any arguments about how much we might garden anything of the left over wild for its sake in our anthropogenic world (re-introductions of extirpated native species, culls of unwanted fertile aliens etc etc), the parakeets are at home right here right now and challenge every idea we might entertain about avian citizenship in any twenty-first century metropolis.

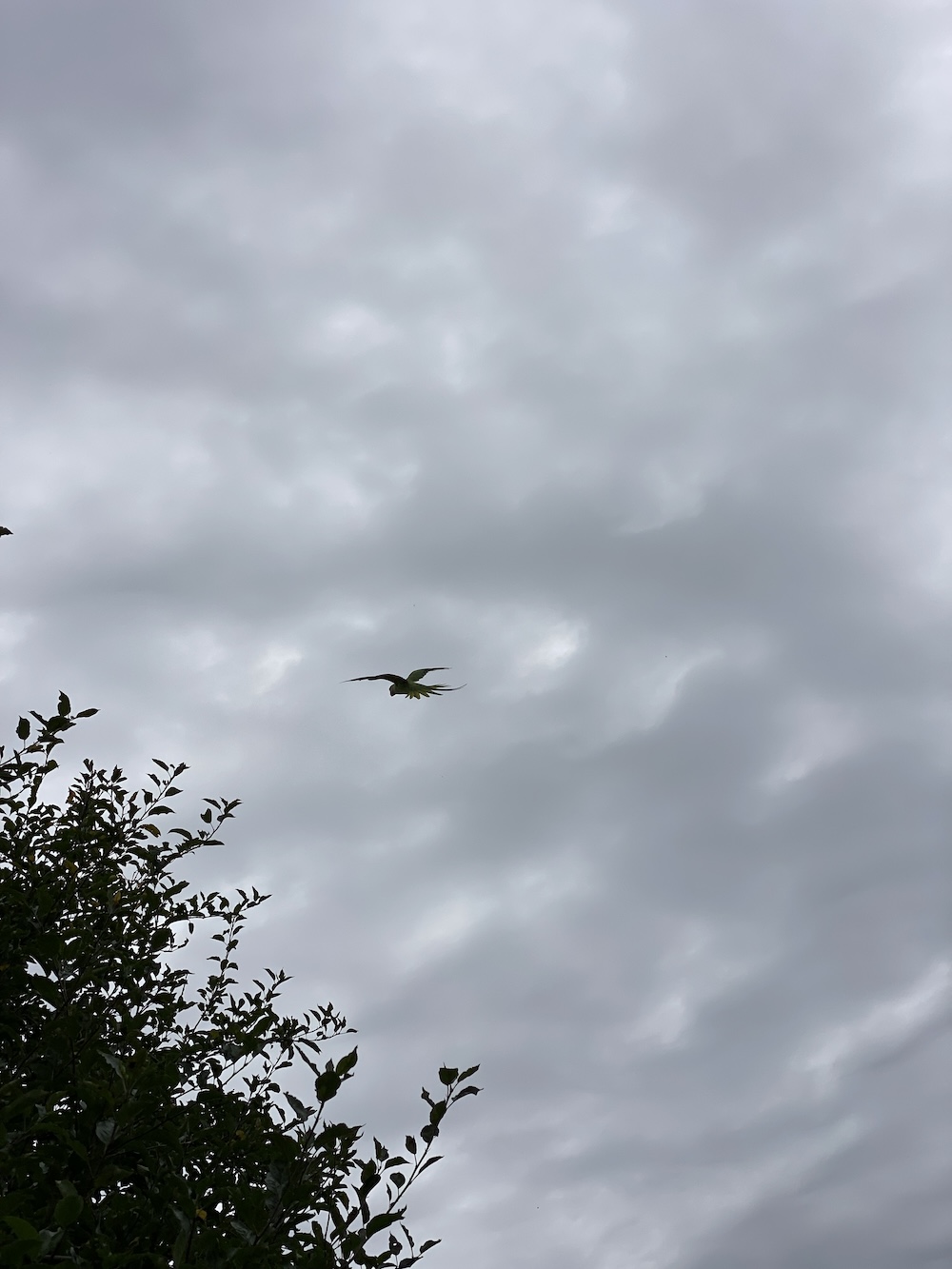

In COVID-era 2021 after a flight from red-listed South Africa to Heathrow I was put on a Home Office requisitioned bus from the airport to a designated quarantine hotel in South Kensington. Heading into the sick city along the Hammersmith flyover and on past the Natural History Museum I saw two quivers full of the long-tailed green arrows launched over the road and understood then something of what it is like to be labelled a toxic contaminant even in the only place you’ve ever known as your real home. And the parakeets have had more to teach. I’m writing at home now in SE24. John Ruskin (1819-1900) lived much of his early life hereabouts and walked many days down the road where I live. What would the high priest of Victorian good taste have made of the exotic birds? Captive parakeets some say are the best parrots of human speech. But who knows what they are saying for themselves. They yakkety-yak out of the expressionless disc of an unbird-like face. They gun their green. They make a fastidious preen. Strange fruit. A cavalcade, a motorcade, Shangri-La and a second line parade. A chemistry experiment. The big bang and a deregulated flock. There is AI in them, there is GPS. There is Tinder and TFL and tlc. They doll up, like pet-shop runaways, like extra-terrestrials, like London at its polymorphous perverse. They’ve run amok and clowned about and still they rule the roost. They defer to none. Dérivers doing the knowledge. Escapologists unsurrendered. They klaxon. They squeak. I heard them on a street scene in Slow Horses. There is a painting by one of the Breughels of the Garden of Eden with two flaming carrot bird comets crossing the paradisical sky (they are Raggiana birds-of-paradise I think); I’ve seen parakeets in flight above Brockwell Park looking like dead ringers for those avian fireworks. They are dramaturgs of the lower sky. Neon ping pong. Pigeons fly faster when the parakeets are on the wing. Crows look confused by them. Parakeets are quicker than thought and louder than bombs. Ad hoc, de-mobbed. Scalextric scooters. Postmodern morphs. Bourgeois bondage revolutionaries. Sherbert fountains. Green knights. Ganglia. Boss birds. Panic on the streets…

Except not really, or only for me. Newcomer pedestrians look up and take in the novelties; but residents barely bat an eyelid, they’ve habituated. The parakeets have joined the Londoners’ roster of cohabiters that manage a mongrel conga through the zone alongside us: gulls come inland for our fast food, peregrines on the high-rise cliff substitutes, sewer rats burrowing in fatbergs, still vanishing sparrows, a pigeon taking the District Line, grey mice like dust balls on the Northern Line, a little egret in St James’ park, and 24/7 fox news…and now, as at the Natural History Museum, the fluttering green crucifix of the ring-necked parakeet squawking its secular introit somewhere half seen up above all of us.

I’m not there yet. They still turn my head. I have made these notes, but none yet has fully caught them. They are not for my sort of getting. And perhaps that is what they might teach us all. They have changed what it means to be wild today. They have claims on being one of nature’s own, and currently most active (perverse, inverted, diverse, marvellous) rewilders. They are making it new. Extralimital in every possible way, no cage of any sort will keep them, least of all something fashioned by people like us. The wonder of them is in that. The take-home lesson of my year was that I cannot love them but also that I don’t need to.

That, at the end of 2024, is what my birdwatching has come down to. The witnessed annulment of one observer – perhaps that is not such a bad thing to get out of a birdwatching life. To discover when watching parakeets in south London that no matter how hard, and for how long we look, all true looking must end up giddily sliding off into the unknown (as Elizabeth Bishop described – and loved – Charles Darwin doing in his nature observing); that we shall never truly know what a parakeet is; that the more we know the more we will know there is yet to know; that we will never hold one in any way. And all that being the case, that we are all therefore to be cut from the great continuum, divorced from the great herd, ushered to the lonely edge of life, and forever kicked out of Eden.

Comet tails. Again, at dusk today. Waving and drowning. Flex and flux. Green falling. Space holding.

*

Tim Dee (1961- ) has written several books on birds, the most recent are ‘Landfill’ and ‘Greenery’, all of them are really memoirs about bits of his life as a birdwatcher. He left the BBC in 2018 after working as a radio producer for nearly thirty years. Before that he wrote a book about the endemic birds of Madagascar and studied twentieth century Hungarian poetry in communist Budapest. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2017 and had tough times with kidney stones in 2017 and, a few weeks ago, in 2024. He has three children, aged 31, 29 and 5; and currently awaits his TFL freedom pass thanks to Jane F. of London SE24.