For Nicola Healey, in 2024, her father’s absence was like the sky.

I think of the last year as ‘the second year’. After a significant bereavement, time stops and splits into ‘before’ and an unreal ‘after’. This rupture happened for me, my mother and my sisters in October 2022, when my father unexpectedly passed away. His absence is ‘like the sky’, as C. S. Lewis wrote in A Grief Observed, ‘spread over everything’.

Lewis captures how all-encompassing such a devastating loss is – it overhangs every moment of your day, night and existence, changing who you are at soul level, in ways that are beyond words. My relationship with the world around me, with nature, with people, and with language and writing itself has altered – I’m a different person, as many of those who have been similarly bereaved will say. I worry I have lost feeling, attunement, spirit and fluency of thought, among other capacities. Sigrid Rausing observes in ‘Notes on Craft’ that a close experience of death ‘hardens you. Scars you’. You are having to get used to not just the irreparable loss, but the secondary loss of self, an excavation that strips you bare, and a necessary rebuilding, and all with a broken heart. It can be difficult for others to read about, or engage with, such asteroid-like impact, as it is too fearful and incomprehensible. It can seem as though it doesn’t contain enough ‘life’, and people generally want to read about life-ful things, and joy, to give them hope. Death is part of life and living though (we could even say that death forces us into life). By avoiding the subject, we ignore this truth, and also ostracise those whose reality this now is.

*

I can’t really write about where I have been and what I have done during this time, as I have not ventured far, and done, it feels, very little. Grief collapses calendar time – time blurs, stutters and rewinds, becomes tangled, so it’s difficult to even demarcate the year as having passed; in some ways, I feel I’m still in 2022. I can perhaps more usefully write about what I haven’t done. I have often felt as cut off as an anchoress. I have on occasion visited the churchyard in Aston Abbotts, Buckinghamshire, the neighbouring village. I walk into the empty church of St James the Great, partly soothed by the familiar sounds, impressions and scents of entering a small country church: the iron-ring handle, awkward to turn as the heavy oak door judders open, and then shut; your feet making the only abrupt sound on the sudden red flagstone floor; the cold church-air smell that hits you reassuringly, the scent of the past; the waiting stillness; the instinct to whisper, even though there is no one here to disturb; the hovering unease and unreasonable sense that your mere presence is a slight impropriety, as Larkin captured so well in his poem ‘Church Going’. My dad always took us to see local churches and cathedrals when we were growing up and on holiday, so I sense him too. For a moment, it could be a hundred years ago. The thick stone walls muffle all surrounding sound and busyness, even the birds and the rustling leaves. They seem to even muffle the centuries.

*

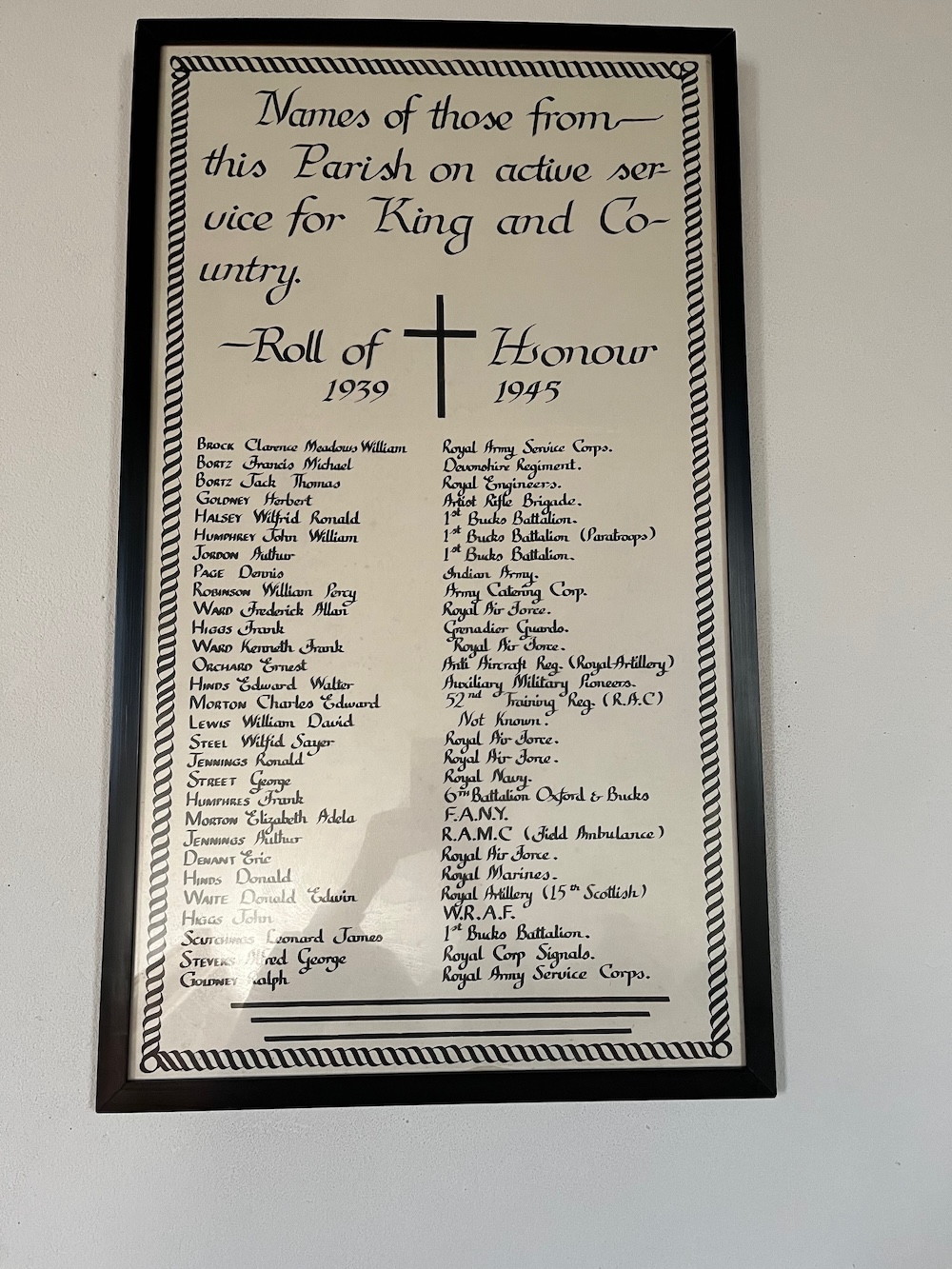

My mother points out to me a list on the church wall commemorating local residents who served in the Second World War. I find my grandpa’s, her father’s, name at the top, in black calligraphic script: Clarence Meadows William Brock. I love the names. He died when I was a baby, so I have no memory of him, just as my little niece will have no memory of my father (which seems unimaginable). Clarence’s mother, Lizzie (‘Bessie’) Brock (née Tomb), my great-grandmother, came to Bucks from County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, in the early 1900s, having grown up on a farm in Tirgarvil, Swatragh, my mother tells me. Bessie became the headmistress of Aston Abbots school and is buried in the churchyard here. These details seem important for me to know, when I hadn’t previously shown much interest in them. Perhaps when your nuclear family starts to disappear, it becomes more pressing to know where half of you has come from, and to recognise hidden lives who have, in turn, gone before; to gather these threads.

*

My first poetry pamphlet was published in April 2024, a goal I had been working towards for ten years. It was naturally overshadowed as my dad wasn’t here to see it. Achievements can feel diluted, bittersweet, if you can’t share them with your greatest supporters and loved ones. Christmas is similarly tainted and difficult to bear. I try to persist with my writing aims both for sanity’s sake and in his memory, and because he wouldn’t have wanted me to give up. Focusing on something – anything – generative also helps to manage the tireless impact of grief, stopping it from becoming overwhelming; it acts as a focal point, a buffer against crushing loss, like those cushioning stone walls.

Re-reading these poems, all written in ‘before’ time, pre-2022, they seem from a different person; it’s alienating and disconcerting. Some of the poems seem written out of grief, even though, other than one, they are not about my father. I think of Nick Laird’s 2021 poem ‘Up Late’, in which he writes: ‘I have been writing elegies for you all my life, Father, / in one form or another’. Anticipatory grief can shadow one’s life long before the loss itself happens. Earlier losses seem only intimations, ‘rehearsals’ for this foundational one.

Most writers will have had the odd, estranged feeling of being confronted with your writing that is from an earlier iteration of ‘you’ (especially given how long it can take to get work finished and published). The work is still true, but it’s distant from its origin. A reader won’t (usually) know of this time lapse and assumes the writing represents, or comes from, the present you. It makes me think of Elizabeth Jennings’s poem ‘Delay’, on the teasing time lag of starlight. It’s a reminder that poems are, like light, emissions, but they are not the whole of us (and that the self is in a continuous state of flux) – poems leave us and live (or drift or go out) elsewhere.

I would be vexed if anyone assumed these poems were a response to this grief. My response to his unfathomable disappearance is mostly silence and fragmentation. Foggy, fractured thinking, like a form of aphasia. As Kate Saunders writes in the Readers’ Edition of A Grief Observed, after the loss of her son: ‘I had a kind of spiritual stroke’.

*

I have written several book reviews this year, something I never thought I would be able to do, but only three poems (one of which found a great home with Caught by the River). Often, I feel I have lost access to language and condensed thought altogether. Prose requires a different kind of energy and capacity (though is demanding in its own way); and when writing on the poetry of others, it’s as though the energy of the poems under review becomes transmitted into you, fuelling your prose, galvanising your brain, for a time. With your own poetry, you’re on your own. For many complicated reasons, grief, I have found, blocks the source of poetry. It requires faith (in oneself, in the future) to persist on the perilous path of poetry, but especially so when one is barely writing.

I take comfort from reading about other writers who have had long stretches of not writing, such as Louise Glück. ‘I have had to get through extended silences’, she wrote in her 1989 lecture ‘Education of the Poet’. In an interview with Henri Cole – published in The Paris Review two months after her unexpected death in 2023 – Glück spoke of the burden of these silences:

It doesn’t feel like a sanguine experience of sitting quietly while the well fills up. It seems like an experience of desolation, loss, even a kind of panic. The thing you would wish to be doing, you can’t do.

In April, I liked reading the poet Elisa Gabbert’s response to Glück’s ‘necessary gaps’. When Gabbert herself was going through a period of not being able to write poems, she sought guidance through the diaries and interviews of writers who were ‘older than [her], and preferably dead’, who had endured, or simply accepted, creative absences, from Kafka to William Meredith. Gabbert writes: ‘I want advice from someone more tired than me, because time itself is knowledge. Who is wiser than the dead?’

*

I am not full of hope, but I still believe in the concept of hope – in the importance of keeping the door ajar to this force. One of my favourite poems in Emily Berry’s 2022 collection Unexhausted Time was ‘(Light)’. The poem meditates on different forms of light, carefully viewing ‘sunbeams that lie on the floor of your room / like ways through’, but ‘they’re not real ways / through they’re just a reminder that there / may be a way through’. I prefer it when writers sift for the nuanced truth like this, rather than saying something more overly optimistic, but which is in fact glib. Ironically, it can be more hopeful and uplifting, in the way that the multifarious light of truth and intelligence is. My sister’s dog has held one of these ‘ways through’. Animals are much more intelligent than we assume, and she, too, was visibly affected by my father’s sudden absence. Part of the balm of animals, for me, is because they are themselves without language; they can be wholly with you in speechlessness. Her name is Dorothy (or Dot), but I tend to just call her angel.

*

In ‘the first year’, I became intrigued by the Latin phrase ex nihilo, meaning ‘out of nothing’ or ‘from nothing’. Creatio ex nihilo is the theistic belief in ‘creation out of nothing’. You don’t have to be religious to find this a helpful metaphor for the hope that, out of nothing, something can still grow. Absence does not mean there is no presence. Nature reminds us of this all the time when new growth insists on emerging seemingly out of nowhere and in the most inhospitable of climates. The fragile crocus spear that pushes through the frozen January ground. And whose tender stem and flower holds its ground even amid frost and snow (albeit, not the battering wind and rain). Their flowers only open in sunlight.

I began four lines the January before last, and this year adjusted one word and a punctuation mark – a fragment more than a poem – a charm or a talisman, to be clutched in the mind like a pebble in the hand:

Out of the dun ground of grief,

crocuses flare their sheer petals,each lilac audacity

a Bunsen burner flame.

*

Nicola Healey’s first poetry pamphlet, ‘A Newer Wilderness’, was published by Dare-Gale Press in April 2024 and won the Michael Marks Poetry Award.