In a text originally written to accompany a recent exhibition of Siobhan McLaughlin’s works at Hweg gallery, Penzance, Martin Holman steps into the artist’s non-traditional landscape paintings.

“If you aestheticise too much,” says Siobhan McLaughlin, “you risk ignoring landscapes for their ecological, social and labour values.” While toil is not the main subject of this artist’s work within the genre of landscape painting, the presence of labour is nonetheless a notable feature. She approaches the task of making imagery by realising in materiality her visual experiences of the external world. They become manifest through the acts of seeing, touching and being.

McLaughlin describes her objective as creating non-traditional landscape painting. For her, that means deviating from the quintessentially British tendency to romanticise the ‘view’ or the ‘experience’ of nature. Because historically ‘landscape’ has been perceived in many instances as a visual salve. The result has been, and I imagine McLaughlin will agree, that notions of the ‘land’, as a product of constant movement by nature and man, has been lost – or, at best, downplayed.

By contrast, her images are constructed with an interrelationship of means. Material layers seem to correspond with physical sensations. We might recognise in the complex edges and surfaces of her work our own encounters with a dramatic natural environment. That experience is inevitably fractured and multidimensional, made up of air, land and sea and the visual tapestry of the piecemeal subdivisions. Mankind has parcelled land into fields and moors, and altered borders to suit changing needs and ownerships, so that echoes of previous patterns remain as vague imprints.

McLaughlin’s use of diverse media and varied techniques articulates that awareness of past employment. The tracery of seams and boundaries across the surface of ‘Our Mount Joy’ (2024) appears random, highlighted in machine stitching embedded in parts of the picture plane. Subtle, raised ridges contrast with smooth and gritty areas, with boundaries between different materialities of facture and of fabric coupled by yarn to enclose raised plateaux that suggest awkward settlements.

The internal edges might be neat or frayed, even trailing a thread here and there. We know nature is not as neat as some preservation agencies would have it; it is not packaged for consumption but pre-exists the rambler’s momentary intervention. The jagged edged multiformity of ‘Untitled (Callanish Standing Stones I)’ (2019) hangs loosely from a fixing in the wall. It strangely resembles a hill climber, grappling the rough surface of the exposed stone it lies against. Colours project an imagined physicality as if the ensemble of textiles that comprise it are willing themselves into three-dimensionality.

‘Untitled (Callanish Standing Stones I)’

As here, a painting’s perimeter can be loose, cockling a little under the effects of handling, coupling and episodes of embroidery. The artwork can appear casual, hung on a hook like a garment worn in the open air. At the same time, it is surprising: an unexpected sighting juxtaposed in the single installation of this show with ‘Our Mount Joy’. Suspended nearby, this time from the gallery ceiling, its expanse confronts the visitor. It dares a response and gradual absorption in its presence. Light draws out and even exaggerates its geography, strafing the surface unpredictably, throwing into relief granular areas of earthy colouring. And the length of it sways gently, unhurriedly, in the backdraft of visitors who enter, pass, circumvent and move on.

Sewing together multiple fragments of cloth into a surface to paint upon grew out of a student’s need for economy. Following her art studies at Edinburgh University, McLaughlin has discovered that divesting herself of the conventional support of canvas, wood or paper maybe anticipated her distinctive structural vocabulary. On the visual level, stitching resembles drawing in thread and drawing is foundational to representation.

So, it should be here as a reference, a touchstone, whether the lines represent or not. Are they paths or walls, features seen in landscape? McLaughlin’s landscape does not need that degree of dependence. Her work can relate directly or not: part of its essential multivalence is her choice to divulge or to withhold, transpose detail into a minor key in order not to overburden the viewer or complicate the encounter.

The provenance of the fabric pieces constitutes a layer in the construction. McLaughlin identifies herself with the contemporary necessity of sustainability, promoting reuse as well as the avoidance as far as possible of substances harmful to the environment. Although the total elimination of staples like oil and plastic media remains impracticable in current circumstances, reduction of an artist’s dependence is within her technical capabilities. She likes to ask for donations of textile offcuts.

Having been belongings, even of people McLaughlin never knew, the textiles forming the picture plane hold histories and personal memories of their own. Others trigger personal memories for the artist, like the curtains from her childhood bedroom, which her mother parted with at her daughter’s request. A fragment of blue blouse in ‘Our Mount Joy’ binds sections of other gleanings, acquiring a transitory pictorial identity within the work’s landscape. Some remnants are saved from waste in the production process. Elsewhere, a piece of purple-grey cloth that, like all, plays a role in spatial organisation was once used in an installation at Tate St Ives.

McLaughlin does not go out of her way to itemise these origins: the onlooker might find out about this practice in a gallery note or be told explicitly by an invigilator or the artist herself. But the degree of information is not established, nor is it calibrated since, beyond general acknowledgement that she works in this way, access to details is not obligatory for her audience. The patches retain the jagged shapes of the original gift. As such, they tell their own story as well as support her impressions of landscape.

For the artist, the situation is quite different: the residue of personal and appropriated memories, sketched notations, ideas and emotions propels painting forward into a divergent conceptual space. Colour is penetrated by this process. Textiles import their own printed colour into the compositions also shaped by pigment derived from natural sources.

In recent work, she has made yellow from birch tree and discovered a variety of pigments in arctic flowers. Stones have colour and when rubbed together, the powder can be finely ground into a pigment. Oxide reds in paintings in this exhibition are distilled from richly tinted minerals unearthed by past mining around Geevor and Lelant. The tones vary with different media and predicting outcomes before drying is acquired through trial, error and knowledge.

Knowing the potential in plants to yield pigments is a product of the exchange of specialist knowledge. Converting these raw ingredients into a coloured solution for the brush is a technical skill involving the time-consuming effort of grinding into workable consistencies. Thus, all her works are tangibly made things. Triggered by specific experiences of nature, they nonetheless stress the part that production occupies in our lived experience of the world.

Art is one process amid many others in their creation; reflecting on that reality permits her to stand back from representation and underline that abstraction lies at the core of composing her imagery. The painted surface is a further layer, a loose geometry of colour shapes and textures derived from different modes of application, from laboriously grinding pigment into powder, from liquid to brush, pen to print, and from handling to sewing machine. Forms overlay the physical matter of the support without complying with the dividing lines within that substrate.

Place is crucial to her, but intuition and sensation are important, factors that combine the different levels of experience she wants her work to register. Walking was a family pastime she first integrated into her art making at Edinburgh School of Art, when ascending Arthur’s Seat, the ancient extinct volcano in the city centre, became a routine. How she perceives her environment on foot informs not just the content of her imagery but also how she puts it together. She has walked the dramatic terrain of the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland, the Orkney Islands and Penwith’s coast and moors, three spatial entities that have been distilled into the single expanse of ‘Our Mount Joy’.

McLaughlin likes to walk in the company of one other. Her choice of partner is partly determined by her location: in unknown territory she will seek out someone familiar with it. That person then shares a favourite route, contributing to the trail of exchange and connections. By these incidental means, movement is incorporated into a constructive process that is both physical and psychological.

Although based in Glasgow, McLaughlin’s affinity with Cornwall has developed through the formal connection initiated in 2022 by the award of a residency at Newlyn’s Anchor Studio by Visual Arts Scotland. That followed receiving the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Award soon after graduation in 2019, awarded by the Society of Scottish Artists and the trust established to promote the reputation of the eponymous Scottish painter.

Towards Lizard Point

Barns-Graham was an alumna of Edinburgh College of Art, training there in the 1930s. Travel was instrumental to the evolution of her visual language into a fluid, abstract interpretation of monumental forms experienced in nature. Her ideas were profoundly influenced by her native Fife coast and south-west Cornwall, two areas she continued to travel between for over 50 years before her death in 2004. The relevance of her example to McLaughlin, therefore, is obvious, and the significance, too, of Barns-Graham’s contemporary in St Ives, Peter Lanyon, also becomes apparent.

Nonetheless, perhaps the strongest agent in clarifying McLaughlin’s aims for her take on the landscape has come from outside the visual arts. Reading The Living Mountain, Nan Shepherd’s exquisite account of relationship with the Cairngorms through walking its high plateaux and rocky outcrops, conveyed the relationship between landscape and interpersonal experience. Shepherd was never overawed by her surroundings: absent from her descriptions is the self-negation associated with the romantic verse (and painting) on themes of the sublime that hung on into the last century. Instead, there is an attitude that has become the principle of ecology: that everything is connected to everything else.

Shepherd’s manuscript was written during the last years of the Second World War and those following. Finding no publisher at the time despite the author’s commercial success as a novelist, the book was eventually published in 1977, at which time Shepherd remarked that “I realise that the tale of my traffic with a mountain is as valid today as it was then. That it was a traffic of love is sufficiently clear; but love pursued with fervour is one of the roads to knowledge.”

In the troubled, uncertain world of its creation, Shepherd found peace in writing. That quality resonates with McLaughlin’s work and the time of its making. The painter relished following in the footsteps of this woman writer. She recognised in Shepherd’s words objectives similar to those she had set in her painting. We can detect a meditation on slowness – ‘a tale too slow for the impatience of our age,’ Shepherd wrote; stress on being rather than doing; and her expression of a vital connection with the natural world. McLaughlin endorses visually Shepherd’s observation that: ‘However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me. There is no getting accustomed to them… the whole wild enchantment, like a work of art is perpetually new.’

We know that the ground is not uniform: it has moved mightily in the past to settle for the time being in contours mounted on hidden strata of minerals. These contain assets that mankind has avidly extracted for centuries as if they were inexhaustible.

The familiar outline in the belly of ‘Our Mount Joy’ recalls the Cornish mine wheel houses that remain in the landscape as relics of centuries of mining. Shafts sunk deep into the rock perforate the county. In that painting’s companion piece hanging in the body of the gallery, ‘Standing stone/Oil Rig’ (2024), the structure embedded in the composition symbolises the extraction of petroleum and natural gas from rock formations beneath the seabed. Platforms have been a feature of North Sea excavation off Scotland’s east coast for 50 years. Cromarty Firth, where this composition was drawn, has become a kind of graveyard for decommissioned structures. McLaughlin conceives the platform’s shape through the deep lens of time, recognising in it an outline reminiscent of Lanyon Quoit, the neolithic dolmen, or stone megalith, 700 miles from the Scottish site in West Penwith. The fluid identity of this detail embodies the geographical span of the artist’s experiences for this series of work. As significant, however, is the allusion to layering land use and mineral extraction with mythology and woven textiles. In this way, she considers mending and care on a bodily scale.

For McLaughlin, walking took on special significance in 2017. A traffic accident in Edinburgh led to the protracted and painful recovery of her mobility. The mental toll has cast a longer shadow. Exertion still involves bodily discomfort in the studio, in everyday life and on long walks, her continuation with which have been markers on her personal road to wellbeing. A natural consequence, therefore, is to think about landscape in a somatic way, as a body, a site of exhilaration and hurt.

In the large-scale work ‘Our Mount Joy’, the assembled cloth is as tall as the artist and as wide as the span her outstretched arms can achieve before she feels pain. Shepherd had a similar preoccupation, which maybe seals the connection between the two women over many decades’ differences in their lives, when she wrote ‘One toils, into the hill’ and, in another passage, she describes ‘a tough bit of going’, phrases familiar to the rambler and to the creative individual. Walking, however, is never regarded as therapy; instead, it becomes ‘one of the roads to knowledge’ Shepherd mentions. Nor does stitching fabrics refer to physical and mental repair. Instead, her story joins others to be fused through skill back into nature.

Our Mount Joy

The notion of a disembodied consciousness is not new and McLaughlin does claim it; she is consciously treading in a tradition and finding her own pace. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the leading academic proponent of existentialism and phenomenology in post-war France, proposed as much in 1945 in his ‘phenomenology of perception’. As relational beings who make sense of the world through gesture, patterns of movement and so forth, we experience the world as a bodily setting. In essence, we are in it and of it, we act in it and it acts in us. This idea corresponds with the knowledge Shepherd demonstrates. She seems to have anticipated Merleau-Ponty’s theory in purely practical terms although, coincidentally, the two were writing contemporaneously in very different locations.

The sense of what both were defining is felt in McLaughlin’s work. “You know who you are by being in relation to things,” she says. Sensory perception has a fundamental role in our understanding of the world. The field notes of the great Scots-born American mountaineer, John Muir, speculated in the 1910s about the role played by the senses in human perceptions of the environment. McLaughlin’s outlook has that heritage. For her, experience of a location is registered by the eye, skin, tread and spirit. These include moving through valleys and hills, changes in weather and light; all need their graphic equivalents.

The body may be both subject and object, sensing and sensed within the landscape. Shepherd knew that: ‘A mountain has an inside’, she wrote. Posture, position and movement shape the internal response while the body among others constitutes the other. Perhaps a symbol of that in these paintings is the contrast between the colour and materials, which stimulate that sensual response, and the elevated position that her images invariably adopt, a bird’s-eye view that seems altogether ‘out of body’. Not surprisingly, Merleau-Ponty argued that reflecting on the world accounts for why we produce objects.

Topographies offer humans powerful allegories. John Muir adhered to a kind of nature mysticism, experiencing the ‘presence of the divine in nature’. McLaughlin admits that her own upbringing in a Catholic household has informed her world view. While she may not go as far as Muir, she gives form to thought on both material and spiritual levels in the open settings of her constructed paintings.

McLaughlin is aware, for instance, of the historical role of walking in demonstrations of belief as manifested in pilgrimages that occur in many faiths. Pilgrims often collect ‘contact relics’, objects of veneration that had touched a saint in life or death, enabling ordinary people to retain some link with a saint as intercessor in prayer or meditation. Encouraged in the Middle Ages, the custom has never really died out.

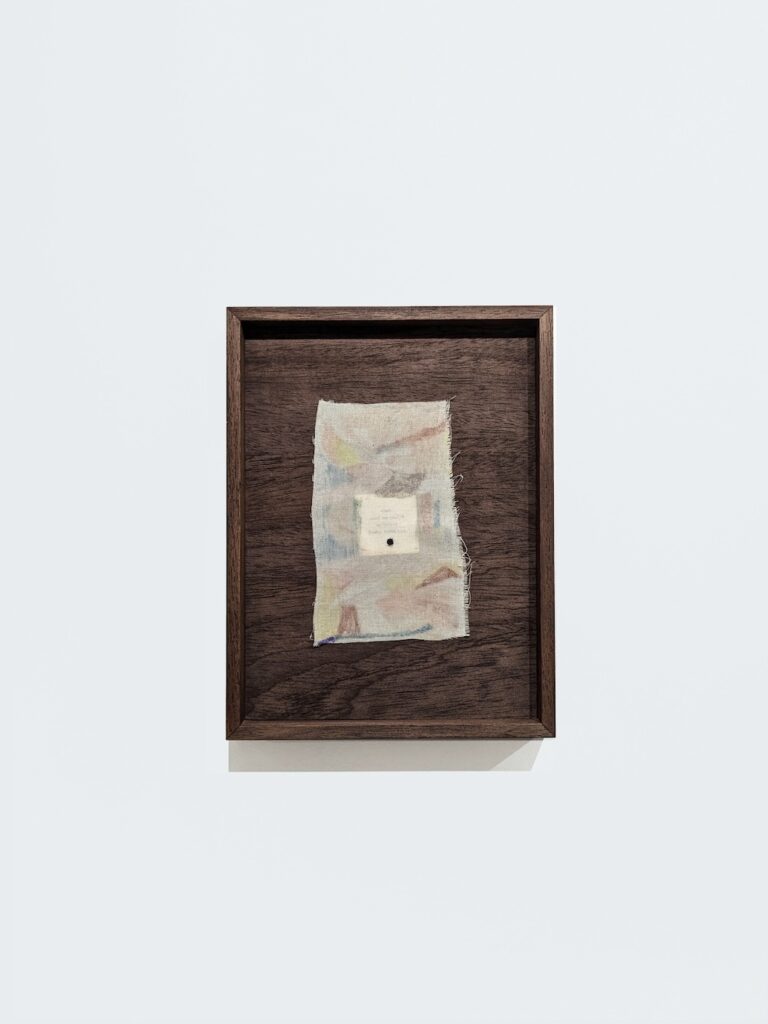

McLaughlin was given a tiny fragment of cloth that had belonged to the grandmother who died before the artist was born. Its plain paper wrapping identified it as a contact relic of Brother André Bessette, a Canadian beatified by Pope John Paul II at a ceremony in Rome in 1982. (André was then canonised in 2010 and has a special significance for caregivers.) The survival of the dark dot of textile attests to its significance for this close relative.

Like the piece of blue blouse, the artist has incorporated the relic into a work of her own, one of three small, framed pieces that seem to encapsulate time, space and memory. Hung with it is her record of the accidental print of textile discovered by archaeologists on a shard of pottery found in Orkney that dates to the same Neolithic era as Cornwall’s Lanyon Quoit, more than 4000 years ago. The third is woven strips of cloth upon which the artist has collected rubbings of colour from plants and minerals as she followed the route, during her residencies in west Cornwall, and along St Michael’s Way.

Relic (Saint Brother Andre)

The trail is punctuated by places where pilgrims stop, often signposted with markers. Such places coincide with an older tradition that associates water springs with pagan spirits that aid the living. Having failed to eliminate the superstition, the medieval Church recruited it to its purposes, rebranding the sites as Holy Wells. Cloth dipped in the water has continued to serve as keepsakes, infused for some with a mystical potency.

Cloth, then, can be imbued with the allegories that communities have for centuries invested in the land. It is this tradition that McLaughlin seems to invoke, creating images that might even be described as secular altarpieces to a body of knowledge that relates mankind to the planet through its own materials. As we live increasingly separate existences from the vital stuff of the world, McLaughlin cannot be more contemporary in her desire to reconnect us.

*

Quotes from Nan Shepherd’s ‘The Living Mountain’ come from the Canons edition, published in 2014 by Canongate, Edinburgh. The edition’s introduction by Robert Macfarlane is also acknowledged.

Martin Holman’s writing about modern and contemporary art has appeared in the publications of public museums and private galleries, and in leading art magazines. He has also published short stories and has organised exhibitions in Britain and Europe. Visit his website here.

Siobhan McLaughlin is an artist and curator based in Glasgow, whose practice combines personal experiences of walking and nature with material experimentation to create non-traditional landscape paintings. Visit her website here.

Hweg is an art space in Penzance, Cornwall. Follow them on Instagram here.