Through a new exhibition at Tate St Ives, Lally MacBeth enters the magic-infused world of the artist, writer and occultist Ithell Colquhoun — where plant, human, mineral and animal coalesce.

Ithell Colquhoun, Alcove, 1946, Private Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

‘Even a bicycle is a hindrance to such communion of person and place, for this countryside, unlike some, is by no means passive but gives to the willing recipient and in its turn receives from those whom it has called to it, and a rhythmic interchange is established.’ (Ithell Colquhoun, The Living Stones)

For almost a decade now, I have been under the spell of Ithell Colquhoun — the artist, writer and occultist who spent much of her life in the wilds of West Penwith in Cornwall. She was until relatively recently virtually unknown outside of a small group of enthusiasts who advocated for her work be given the recognition it deserved. A moment of change came when in the summer of 2019 the Tate (who already housed most of her paper archive) acquired a large collection of her paintings and other visual works from the National Trust. She has since then climbed to fame and now has not only a line of Dr. Martens featuring her paintings but a newly mounted retrospective at Tate St Ives, Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds. It is the first of its kind, and features many works that have never been seen outside of private collections.

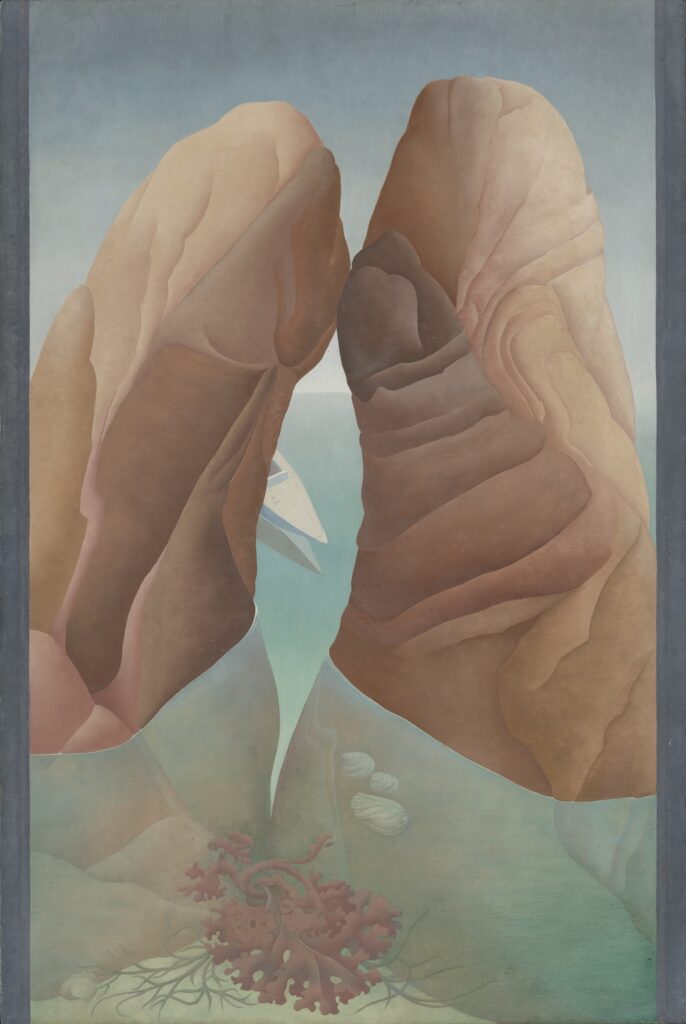

Ithell Colquhoun, Scylla (méditerranée), 1938 Tate: Purchased 1977 © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

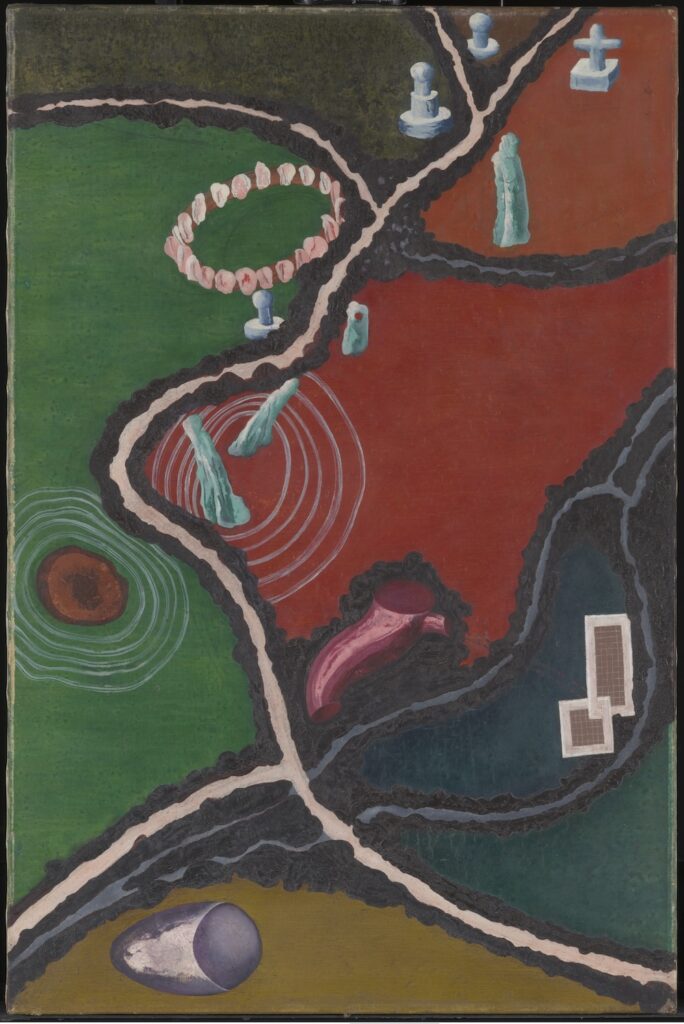

Ithell Colquhoun’s world was one which was infused with magic. She did not believe herself separate from the landscape she lived and worked in but rather as a part of it. In her travelogue of 1957, The Living Stones, she writes about Cornwall as a living, breathing, animate being filled with creatures, humans, trees and stones that danced, writing evocatively of: ‘Stones that whisper, stones that dance, that play on pipe or fiddle, that tremble at cockcrow, that eat and drink, stones that march as an army’. This absolute understanding of there being no line between life and death, inanimate and animate is apparent from the very beginnings of her career. She was entirely focused on the coalescence of plant, human, mineral and animal. Taking a largely chronological format, Between Worlds begins in the earliest moments of Colquhoun’s painting experiments with a series of renditions of mythical scenes executed whilst she was studying at The Slade in the 1920s. These transition into her first investigations into surrealism; collages in the form of ‘Bonsoir’ (1939) an unrealised series intended to be brought to life via film, and wonderfully dual images of human forms made up of seaweeds and vegetation in the form of ‘Scylla’ (1938) and ‘Gouffres Amers’ (1939). Viewing the two rooms it might at first seem like Colquhoun made a large unconnected leap from the fairly classical mythical worlds of her college paintings to the wild surreal imaginings of her early thirties but there is a golden thread that connects them. They are all very much alive. There are entities that hide in the cracks. Colours that swarm, and figures, and motifs that appear in image after image.

Ithell Colquhoun, Attributes of the Moon, 1947. Tate, Presented by the National Trust 2016. © Tate. Photo © Tate (Matt Greenwood)

Her later explorations into surrealism take a more automatic form with techniques such decalcomania and stillomancy rendered in vivid colour, but again there is a guiding thread of animism between the rooms. It also becomes more readily apparent, as the exhibition continues, the importance of colour in Colquhoun’s work. Until this point, I have only seen fuzzy reproductions of many of her paintings in books. Seeing them here in all their technicolour brilliance is a true revelation; colour was clearly of deep and magical significance to Colquhoun throughout her life, and having the works available for study in this way will surely unravel some more of their secrets. Perhaps some of the codes she was using will become clearer, because there is no doubt that whilst we now consider many of these works art, Colquhoun saw them as magical acts or as objects infused with codes and signifiers.

There is a room that deals directly with her magical workings, making particular reference to Golden Dawn colour theory and her experiments with Tessaract, and then a room that deals with her work in relation to the landscape and earth energies, and a final room that deals with what is often spoken of as her lifetime’s work; her series of Taro cards (Taro was Colquhoun’s chosen spelling). At times it feels a little jarring that a distinction is made between her magical works and her paintings. My feeling is that she believed it all to be intertwined, and this certainly comes through in the work and curation, if not always in the interpretation.

Ithell Colquhoun, Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna), 1950. Presented by the National Trust 2016 © Tate

It is known that Colquhoun was interested in multiple magical orders, and worked with multiple systems across her lifetime. However, she was rarely successful in her admittance to magical groups — she writes herself in her book on the history of the Golden Dawn, Sword of Wisdom, about her rejection from the recently formed Alpha et Omega. The only group she is known to have spent decades studying and practicing with is The Druid Order. It is a shame then that this seemingly incredibly influential and important part of her life is not better represented within the exhibition. It is certainly an area that would no doubt provide further insight into some of the unknown and more esoteric aspects of her work. Likewise, it feels there are aspects of later processes that have largely been ignored. As she grew older, perhaps due to failing health and decreased mobility, Colquhoun turned to using found materials which she formed into collages: eggboxes and stickers notably, but also felt tips which she used to render wonderfully surreal still lifes. Many of these have a quality which is more ‘folk art’ than ‘high art’ and this perhaps is why it was deemed they did not fit amongst her more impressive large-scale oils. However, for me there is a tenderness in these later pieces that humanises her more esoteric work. They speak of a woman who after a long life of moving between continents, and through space and time, was trying to find new ways to continue to work. It is easy perhaps to dismiss them as comparatively mundane, but I would argue that in the mundane, Ithell finally found the magic she had spent a lifetime searching for.

*

‘Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds’ is on show at Tate St Ives, 1 February – 5 May 2025, and will then move to the Tate Britain from 3 June – 19 October 2025.

‘The Living Stones’ is available from Pushkin Press.

Lally MacBeth is an artist, writer and curator based in Cornwall. Her work takes in history, folklore, performance, ritual and artifice – and the links between high and low culture. She is the founder of The Folk Archive and co-founder of Stone Club. Her first book, ‘The Lost Folk’, is published by Faber in June.