Winter winds blow gulls and otters to Kirsteen Bell and Annie Worsley’s highland crofts.

Dear Annie,

I had thought to write to you about the shore, about the single curlew glimpsed from the car window, the slow gather and spread of seaweed to fertilise the desert-like hydrophobic soil of the polytunnel, but it would only be a tiny thread of the story, and perhaps a disingenuous one.

I’m tired. Tired of it never feeling enough, of it only being one curlew, instead of the herds that used to tip through these waters. Of the seaweed feeling like a hard-won sticking plaster over soil that might be better off if I left it alone altogether – might be better off tearing the plastic tunnel-covering down, let the birch throw its seed across it all, their leaf litter the real solution to the tired soil. I’m tired of clutching at straws, of not knowing whether this land would be better off with our interventions or with our abandonment.

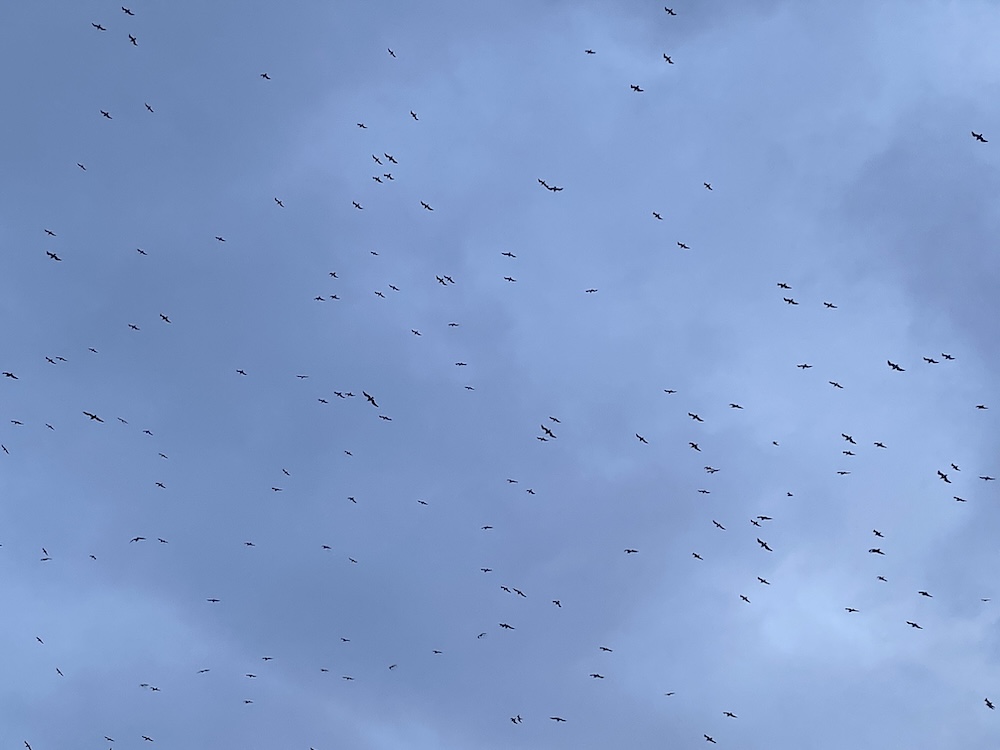

So instead of writing about the shore, or the soil, I want to write to you about the gulls instead. So many gulls, Annie, poured into the skies between our hills, flickering clouds of shredded paper, bright as plastic, or grey as ashes from a fire against the snow still brindling the uppermost slopes.

They are light and shadow all at once, dark wing tips fading to blinding white at their breast, voracious squabbling vermin with a supple strength and grace that flows with the pewtery sky. Common and herring, lesser black back, great black back, and even the occasional Icelandic gull, dotted along the headropes between the floats of the mussel farm in the loch by the croft, picking through the rich bronze seaweed exposed at lowtide. I turn my head up at any time of day and see hundreds of them etched sharply in the air, pale shards drifting on wind, converging in deep helixes above the water.

I suspect it is the sheer volume of gulls that means there are no longer curlew such as there were when I first came here nearly twenty years ago. No groundscrape of eggs would be safe from the dense net of gulls that sentry the shoreline and sweep the grass and heather on the hill above.

At the top of the croft, you are exposed to the wild cacophony of sharp mewing calls as they gather in hordes around the landfill across the fence. They congregate on the metal sheds and across the open cells of rubbish, a steadfast presence. But their noise doesn’t jar my bones the way the dump’s rock-breaker does, or the metallic flow of the tippers being emptied.

I should hate them, resent them for stripping the land of other life. I will admit to being exasperated if they shit on the car – whatever they’re finding to eat up at the landfill burns through the paintwork leaving splatters tattooed across the metal. But sometimes I am envious of them. That they actually don’t give a shit.

They’re doing their best to live alongside the landfill the same as the rest of us. No, not just living alongside it: they thrive off it. And they are utterly unbothered by any attempts to dissuade them from their goal. If a dump machine storms towards them, they casually swell up into the air en masse, gently drifting back down again to resume their posts with a lazy nonchalance that I aspire to. I am calmed by them. My eyes drift with them, responding to depths and currents I couldn’t otherwise see, white crests on invisible waves of wind.

If I am honest, I don’t know if I should view the gulls with distaste, or awe, or quiet consolation that there is any life at all. Probably all of the above. I think my weariness gives an opening to acceptance though. Is it a kind of giving up? A neat narrative that absolves me from responsibility of fighting for any of this? Instead of calming me, should those storms of gull-flight be kindling my rage? I can’t find it in me to blame the birds though, and I wonder how I can hope for the gulls and the curlew at the same time.

Ach, maybe it’s just the relentlessness of winter, or I’m maybe just tired from work, and family, and croft, and the endless ‘shoulds’ and decisions that need to be made. It’s been a busy time. Finding a moment to write these words to you though is like that brief glimpse of the delicate dipping bill of the curlew. I am grateful for it.

I’ll sign off for now, but I’ve included a gift of a wee poem too below.

In shadow and light, always,

Kx

Gull

Canny gawker,

raucous marauder,

caustic shiter:

calls for culls.

Untold scraps of white let fly

arcing endlessly, windborne yet free,

between the absolute of sky

and the grey glimmer below.

No thought

for either.

*

Dear Kirsteen,

Thank you for your letter. And your poem! Oh my, it is evocative. Your descriptions of gulls around your croft and shore are gorgeous – ‘pale shards drifting on wind, converging in deep helixes above the water.’ I love this! Gulls are here too, but perhaps not as insistently. When storm winds growl in from the northwest, great gangs fly inland and settle on the hill lochs, sheltering from the worst. Then, when the weather quietens it’s as if a school bell has rung and they fly back, flowing down through our wee valley towards the sea. A river of birds. Their meetings are raucous and loud, like children running out through the school gate to meet family and friends.

When the winds are kinder, I can stand at the cliff top near home and watch the gulls sail past, following the surges of tides and waves. The appear to be in family groups and although I know something of their flight paths, their lives are mostly mysterious to me. I often see gull-groups of different kinds but my birding skills are so poor, my ID lists are thin!

There is no lucrative site for gulls here, no landfill or obvious (to me) food source, so our curlew numbers are reasonable. Although ground nesting birds such as red grouse and hen harriers on local moorland and the oystercatchers and ringed plovers along the shore are predated, they are holding on. Often dogs belonging to careless owners cause more damage. (I have a dog, Dram, but spent a long time teaching him to keep close, sit or lie quietly while I looked out for our wilder neighbours. He’s a good nature watcher! And calmer than me!) When other dogs charge around the shore especially at nesting time… oh my goodness, I burn with hot rage.

How close is the landfill to your croft? Do the gulls cause damage to your mussel beds? I would love to come over to see how you farm both land and sea! Lots of questions today, Kirsteen! How did you fare in Storm Eowyn? Living on the fringes of the Minch means strong winds are ‘the norm’ here. We’ve been putting up with nameless storm after nameless storm for years and years. Gusts of 50 to 60 mph regularly pound this coast but even when they arrive wrapped up in the familiar ‘low pressure’ structure seen on weather forecasts, with swirling fronts and tightly bound isobars, more often than not, they aren’t named. I suppose we are used to it! I lament for the wildlife though. Finding food is hard when storm winds blow, especially for the smaller birds.

Storm Éowyn came with powerfully thrusting westerlies. Did you escape unscathed? Our wee house is protected by trees and high hedges so we were lucky – just the panels from the greenhouse pushed out again, not by the gusts but by rapidly changing air pressure. When the centre of the low passed over Wester Ross, the barometer dropped so fast I ended up with lotion all over my jumper. I’d just opened a small bottle and whoosh, out it came, like a miniature Plinian eruption. That has never happened to me before! Strangely, as the winds gained speed, birds gathered in the garden on the leeward side of the house. There, in the shelter of house and hedge, they sang and danced and fought and squabbled around the bird feeders.

I have just come in from the shore. There was a lovely calm spell and the clouds had cleared letting in the sun, so I grabbed my coat and went with Dram to see what was going on. The late afternoon light was delicious, all pale gold and opal; the sea was all silver and shimmer. The tide was very low and along our Erradale shore, the kelp beds were exposed. Their fronds caught the light and as the gentle waves brushed past, they seemed to shudder. I sat facing the sun so although I could hear birds singing and piping, oystercatchers mostly, I couldn’t see them. And then, in the nearest swoop of water, a mother otter and her cub. At first, they were shadows in the golden light and then their silhouettes made sense. They play-fished amongst the glistening kelp and whistled their evident joy (or so it seemed to me), and out-sang the oystercatchers, if such a thing is possible.

I think I needed that hour of calm. Like you, I’m tired. Though I love storms, just occasionally, instead of feeling invigorated and renewed, I feel exhausted, as if the winds have stripped me of my energy. And I’m old, so I need every precious drop. But I understand how you feel. There is so much trouble and strife in the world – the big political changes happening everywhere, the relentless assault on nature, the selfish greed on display, and the anger! When I think of the work done as a young woman, a young scientist, to help fight for clean air, clean water, clean earth, I feel utterly dejected. For a while we rejoiced in the successes. Now, it seems, we have gone backwards. I’m upset because I missed the point at which things were plunged into reverse.

But we do what we can. You manage your croft and marine enterprise with the care and love they need, with nature and environment at the heart of your endeavours. We are the same here. And we’ve had successes. Biodiversity has increased, fish, bird and insect numbers are up, and we have created a small area of native woodland. So, we can do things to help the natural world. And in doing so, we build hope for the future.

Your ‘curlew-hope’ is powerful and will give you strength. As daylight grows, you will feel its energy coursing through your body. So, dear mother-crofter-marine-harvester-writer, carry on with your work. Keep writing! And I don’t mean just these letters, which I treasure, I mean your creative works, your poetry and prose.

I now carry your gull poem as a blessing.

With love, Ax

*

Kirsteen Bell is a Scottish writer of narrative non-fiction and sometimes poetry. All her words are gathered from the croft in Lochaber where she lives, and the surrounding Scottish Highlands. Her writing and reviews can be found in such places as Paperboats, Caught by the River, The Guardian Country Diary, The Lochaber Times, and Northern Scotland Journal. Kirsteen can also be found at Moniack Mhor, Scotland’s Creative Writing Centre, where she is Projects Manager and Highland Book Prize Co-ordinator.

Annie Worsley is a writer, crofter, grandmother and geographer with an enduring love of the Scottish Highlands. In 2013 she and her husband moved to the crofting township of South Erradale near Gairloch. While her husband was a community pharmacist, Annie worked on Red River Croft. She began a blog about life on the croft and then wrote essays on nature and environment for various publications including Elementum Journal, Women on Nature, the Seasons’ Anthologies edited by Melissa Harrison, Caught by the River and Inkcap Journal. Her first book about life on Red River Croft and the natural history of Wester Ross, ‘Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands’, was published by William Collins in 2023, and is out now in paperback.