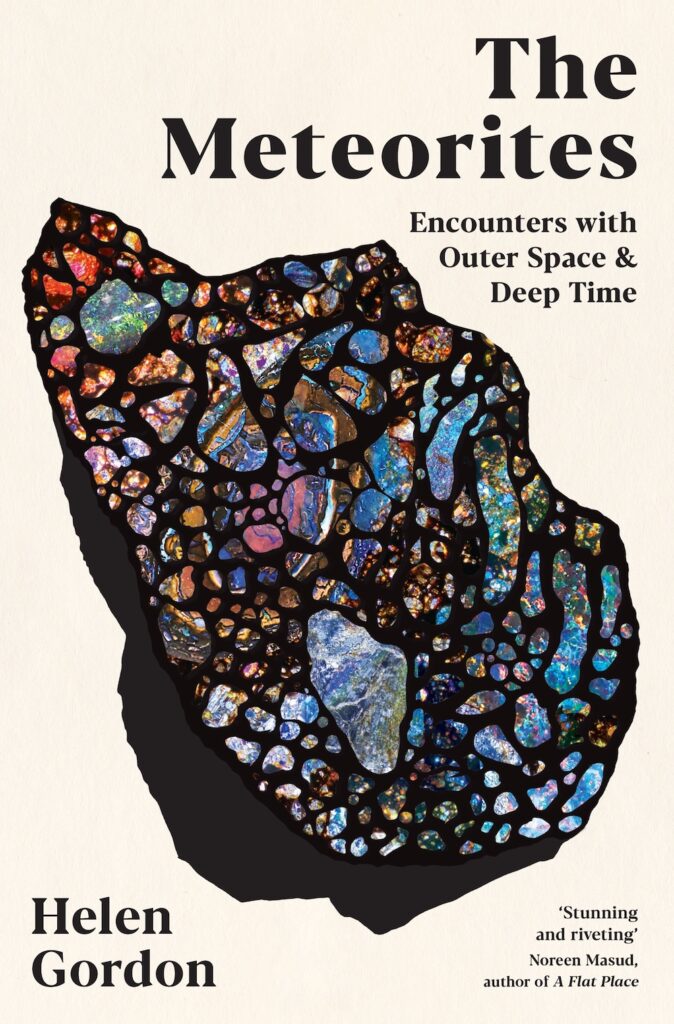

As her book ‘The Meteorites: Encounters with Outer Space & Deep Time’ is published by Profile Books, Helen Gordon shares her fascination with these ancient, extra-terrestrial rocks.

It was one of the largest meteorites I’d seen: 635-kilogrammes of iron nickel backed up against a pillar in the museum as though no one knew quite what to do with. A lumpily blackened thing tinged with red rust, weighing about as much as a cow. I kneeled down next to it and there was a smell of old coins. It was earthy, solid, heavy. From one angle it looked like the skull of some snouted, prehistoric creature. Difficult to believe that rather than being dug from the ground, pulled up from earthy darkness, it had flown towards us through the air, had dropped down through our clear blue skies.

The Campo del Cielo (Field of the Sky) meteorite was discovered in Argentina first by the indigenous population then, in 1576, by Spanish explorers. It probably arrived on Earth some 4,000 – 5,000 years ago, but its true age is far, far greater. Most meteorites were once part of asteroids – the rocky, airless remnants left over from the formation of our solar system around 4.6 billion years ago – making the Natural History Museum’s specimen older than the Earth itself. On entry into Earth’s atmosphere the meteorite broke into many parts and today pieces of Campo, as it’s known in the trade, can be found in museums and private collections across the world, while even larger masses still rest where they landed in the Argentinian countryside.

In the gallery the meteorite was a mute, hulking presence. From the stone’s perspective my lifetime was a flicker; less than a flicker. I wondered, were we actually allowed to touch the thing? Certainly there were no signs warning me off, and earlier I had watched two little girls gently stroke the meteorite’s dark flank. I stretched out my own hand, conscious that this would be the oldest object I would ever touch. Earthling meets extra-terrestrial. Human skin against cold, slippery rock.

At some point, reasonably enough, people began asking why I wanted to write about meteorites. Turning over the question one evening while picking up the children’s toys from the rug, I thought about how I’ve always been drawn to encounters (with places, objects, ideas) that evoke feelings of awe and that sense that our lives are very small, the world very big. To survey a looming mountain, a vast ocean, a roaring waterfall, can be cathartic, invigorating, even. The glorious immensity of it all, the frisson of terror, removes us temporarily from everyday tediums — the children’s toys to be tidied up, the pile of unread emails — and from the too-often nagging, self-critical inner voice. Life in London’s outer suburbs with two children under the age of five is in many ways wonderful but, it must be said, provides scant opportunity to gaze upon mountains or oceans. Those wishing to encounter the sublime rarely take the train to Croydon.

My husband was in the kitchen cooking supper. No sounds from upstairs where the girls were, hopefully, asleep. That afternoon they had been playing farms. In front of me were black-and-white cows the size of my index finger. Chickens no bigger than my thumb nail. An incongruous blue dinosaur standing beneath a wooden tree the height of a daisy. With my children the world had expanded, sure, but it had also shrunk. Miniature animals and trees. Quarter-sized knives and forks in the cutlery drawer. Shoes that nestled in the palm of my hand. With the two of them a trip through the woods to the playground could take all afternoon in the planning of it, the execution, the recovery.

Opening the back door, I stepped outside into the darkened garden. That evening the sky was mostly a featureless blur. Clouds hid the stars. Purplish mist drifted around the flat half-circle of the Moon. After a while, though, I began to notice one bright yellow star winking in and out of view as the clouds rolled around. Not a star at all, actually, but the planet Jupiter shining in the winter sky.

Most meteorites are fragments of asteroids, meaning that they probably began life in the asteroid belt, a region between the orbits of the planets Mars and Jupiter, filled with strange, airless worlds, the smallest less than 10 metres across. Tiny rocky landscapes hurtling through space. At the point closest to Earth the belt is 1.2 astronomical units, or 111.5 million miles away from us. Incredible, unfathomable distances. When I looked towards Jupiter, I was probably looking towards the home of the Campo de Cielo rocks and all of the other meteorites I had been writing about.

Many of the people who work with meteorites once dreamed of being astronauts, their childhoods filled with Star Trek and posters of the solar system and glow-in-the-dark ceiling stars. It makes sense. Meteorites are a tangible, graspable connection between our Earth-bound lives and the planets, moons and stars – the great otherness of space through which our world spins. There is something called the ‘overview effect’ – a term describing the sense of awe and self-transcendence that grips astronauts looking back towards our Earth. As the Italian astronomer Roberto Trotta puts it: ‘By looking up at night and contemplating the remote, unreachable suns scattered in the infinite inhospitable darkness, we can all experience a “reverse overview effect”.’

Back inside, back in the warmth of the house, I picked up my own meteorite. Sometime after I’d been to the museum, I bought a Campo specimen from a dealer I’d met at a meteorite show. (Campos are good entry-level meteorites, small ones affordable for a child with some birthday money, or an adult with a sudden passing fancy.) My fragment was a tiny, uneven, blobby thing like a drop of melted solder, coloured somewhere between silver and bronze and smelling strongly metallic. Once it was the molten core of an asteroid, now it lives on a shelf overlooking my battered dining table, the radiator draped with towels and swimming costumes, a pair of muddy trainers by the back door.

I stood holding the meteorite for a moment. Outside, both Jupiter and the moon had disappeared behind a cloud. The sky was just a soft inky blackness, a little lighter where the moon was hidden, a little red-tinged from the lights of the city. No stars. A curtain fallen between us and the rest of our galaxy.

It is so easy to forget what is out there and what we are a part of. Meteorites make us aware of our status not as inhabitants of, say, London or Great Britain or Europe, but of Earth. Earthlings. Creatures that live among stars. Beings far more alike than not in the context of the vastness of space and the deepness of time.

*

The Meteorites: Encounters with Outer Space and Deep Time by Helen Gordon is out now, published by Profile Books.

We have three copies to give away on this afternoon’s newsletter; make sure you’re subscribed for entry details. The sign-up box can be found in the sidebar at the top of this page.