Tim Dee on scattering his dad far and wide — and the radio programme he made along the way.

To infinity and beyond! Some rockets, an urn, sticky backed plastic, and some of the ash of John Dee. Minehead 2021

Many people get it over in one dump. Some people never get around to it. I know a woman who has her late partner in a flowerpot on top of the toilet cistern in their spare bathroom. Half a friend of mine has been shelved by the back door to his Bristol home since he died in 2018. I’ve heard of people of my age inheriting their grandparents’ cremains along with their parents’. I once saw the basement of a crematorium in Moscow crammed with unclaimed urns – dozens lined up like a stone-grey army waiting for the crack of doom, or the whistle blow, that would send them all over the top to be scattered into so many future deaths: the dead all set to die all over again, and then again, and again.

*

BBC Radio 4 have devoted thirty minutes of airtime this Sunday 2nd February to the contents of just one urn: my dead dad’s ashes. The programme is called Scattering and goes out in the (newish) feature slot called Illuminated. After the broadcast it will be available to listen on BBC Sounds.

*

Listening Back

My father died in 2020. I scattered his ashes in thirty or so places throughout October 2021. Just a couple of weeks ago, in mid-January this year, I returned to some of those drop sites, with a tape-recorder and two radio producers, to restage half a dozen ash-falls and to remember and think on my father, both dead and alive.

He will speak in the programme. I can’t now recall the mechanics or location of the session but on 1st February 2004 – twenty-one years ago today – I sat with a minidisc recorder for an hour or so in front of both my dad and my mum and got them talking about their early years – the people they came from and grew up with and the homes they occupied. They were both a little older then than I am now and sixty-plus years of banked memories came readily forth. Many original stories were spoken out loud. Worn-out family jokes were rehashed. Long held family lore was retold. And new discoveries too were brought up, things (incidents, relatives) I hadn’t known – family stuff or the matter with us all.

We filled two SONY 74-minute minidiscs. I labelled and dated the recordings, ‘Dad’s Memories’ and Mum’s Memories’, and dropped them, when next in work, into one of several boxes I kept in my BBC office of ¼-inch reel-to-reel tape, cassettes, other minidiscs, DATs, CDs, and soundcards – the material legacy of three decades of my employment as a radio producer. A single tape of my two older children (toddlers, then, on a train journey) and these parental childhood-memory sessions joined a spating river of something like five thousand voices of all those (poets, painters, musicians, novelists, naturalists, historians, weathermen, dancers, actors, critics, comedians, philosophers, acrobats, clowns, politicians, citizens, et alia, etc.) who I had talked down onto tape across close on thirty years. I might have a whole year of that time taped, 8760 hours of talk…there might be still more – I had pressed RECORD a lot, it was my job.

On leaving the BBC in Bristol in 2018 I ferried (with corporate permission) all these tapes from a basement storeroom at Broadcasting House to my flat a couple of miles away. I knew I had been busy, but I hadn’t thought the airy archive would take up so much room. Even before I finished unloading, my home was choc-a-bloc with ziggurats of boxed-up sound. I couldn’t get to my bed that night. A friend, Mark Cocker, came to look at the flat and renamed it my Bat Cave.

More crated Dee clutter had to be accommodated after my father died in 2020, and my mother in 2024, and their final home in (the last resort) Minehead in Somerset was cleared (a bit by me, mostly by my heroic sister). I took delivery of the terminal moraine (ash and otherwise) of my parents on a day in December last year when – coincidentally – a kidney stone began to – agonisingly – exit my own premises during the hours I drove from Minehead to Bristol behind the removers’ delivery van. The stone passed (though another lurks within my wounded plumbing), but that last load of inherited material brought my entire enterprise to a critical tipping point.

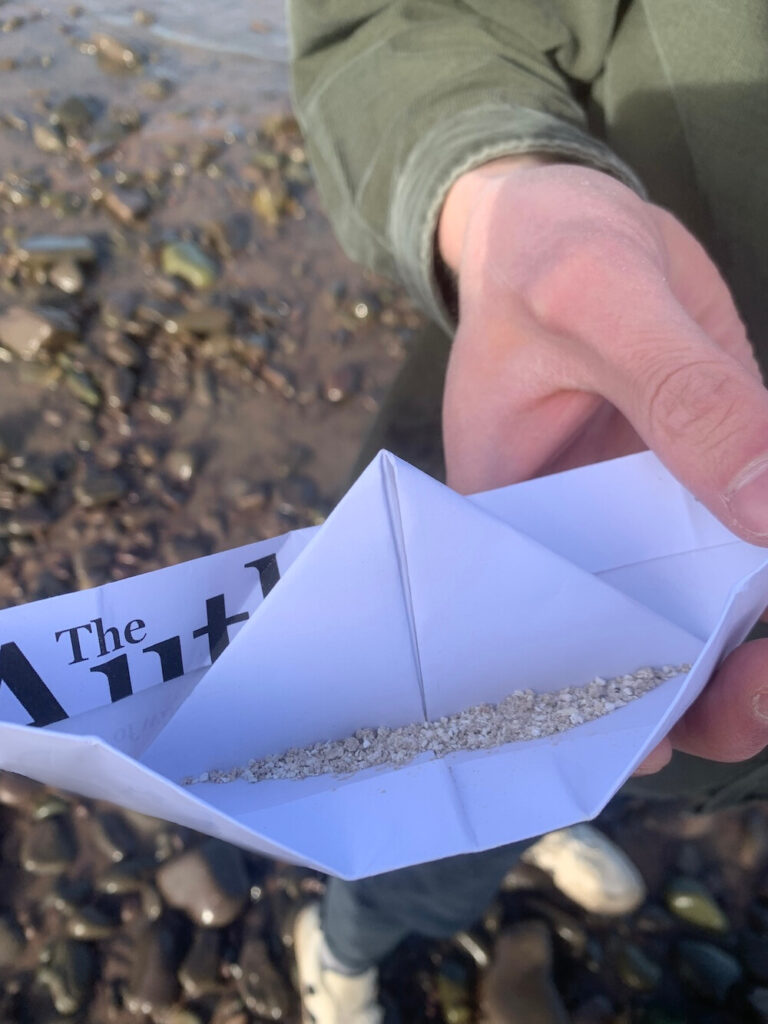

At Mad Brain Sands, Minehead, a paper boat with some John Dee ash aboard. Setting out to sea. October 2021

In my flat, high-stacked boxes had made beetling cliffs and leaning towers. Adding more items to my inadvertent museum threatened to unbalance the lot, collapsing the edifice, and most likely injuring if not burying its bemused curator. That was a frightening thought, and it prompted some remedial action.

I have got some living room back now by paying for a padlocked iron cage to keep the BBC taped soundings in a safe house elsewhere in Bristol. I have vowed there will be no further acquisitions from any source and that once (ha ha) I have made an inventory of what is in the boxes I promise to dispose of most of their contents. I should say bin or chuck out but fear I’m not cool-headed enough yet to talk that talk. It is also true that wanting to write about my clearances has stopped me doing it. I am still to sort the bulk of the boxes and can see no speedy way through the jumble. I am not a bat, despite my accommodation, and have no echolocation skills; nor, I sense, will I know, before I get around to it, exactly how to pan or mine my shambolic inheritance for any value-added nuggets or sustaining rifts of emotive ore – indeed I am not even sure there are any such take-homes to be discovered.

It was the relocation of some of my Bat Cave boxes that brought to light my parents’ memory minidiscs. I hadn’t listened back at the time they were made, and I hadn’t thought of them since, but I spotted them slaloming from a broken cardboard box as I was hoicking assorted BBC tapes into other containers earmarked for my new lock-up. I put my parents to one side on my desk. I didn’t listen to them then (though there is an old but perhaps still functioning minidisc player somewhere in my cave), but when trying to scope out how I might tell some of my ash-scattering odyssey for the radio it occurred to me that my recorded dad could ghost his own ghost story.

So, it might be. My producer (Alastair Lawrence) and our executive producer (David Prest) have taken the minidisc and dubbed snippets of my father’s talk. I have been able to hear him speaking for the first time since he died. David remarked on my dad’s posh voice and Alastair is keen on a clip where my father light-heartedly describes the auspiciousness of his buttocks-first breech-birth. As I write, the final mix of the programme is still underway. Perhaps some of my dad’s talk will merit inclusion as a sonic texture or a verbalised wildtrack to run beneath and between scenes in the story. Wind and birdsong more commonly fill this role. And sea-wash and traffic skylines. But my dad is somehow both the sounding undertow of our programme and its leading man, which makes me want to have him as much as possible present throughout.

*

My dad died that day in March 2020 when Britain went into its first COVID lockdown. My mum, and my sister Jenny, had been permitted to see him one last time in the hospital in Minehead. He was then cremated, like a vagrant stranger, by the local Somerset authority, with no mourners permitted and with no service of remembrance. His ashes were stored at a funeral parlour – like mail with an address unknown returned to its sender – for more than a year. Only then did I get to see him. On my first trip back from where I’d been living in South Africa, I shifted a cardboard tube containing his three residual dusty kilograms from the undertaker in Minehead to his last residence there. Only then did he make it home.

He lodged for a while by the cat’s litter tray – worryingly similar in appearance – but I had other ends in mind for him. With the blessing of my sister and our mum, and as an alternative to any more conventional or commonplace valedictions which the times had denied us, I had planned a tour for dadash that would deposit his leftover granules and grits and grains in thirty places that I knew or believed had been significant to him.

At Mad Brain Sands, Minehead, John Dee in ash form ready to launch. October 2021

Every day for a month I went out with him in a makeshift hearse, my Toyota Yaris. I drove him to one spot or another, mostly in the West Country at points between Bristol and Exmoor. And there I spread or sprinkled or scattered, from a recycled yoghurt pot or chicken tikka takeaway tray, some dusty-ashy quintessence of John Dee.

Doing this to my dead dad, my living dad came much to mind, so sometimes I talked to him, once or twice I shouted and swore at him, and sometimes I sulked and said nothing. Sometimes we listened to the music that the radio sent our way, sometimes I had thought ahead and planned a soundtrack tailored for the day’s drop and I played that playlist. Sometimes we just listened to the autumn wind. Every time a bird crossed our path, I called out its name as I had ever since my dad had started me off as a birdwatcher when I was six or so.

I’m not sure what he would have made of it all. He would have liked being the centre of attention though I had some tough judgments to pronounce. Alive, he would bat away unwanted questioning with a dismissive wave of his hand – a signature gesture for him. Dead, I suppose, if he could hear anything at all, he would have had to listen to what I said. He was a deluded, near-bankrupt failure as a businessman, and he stole money from his own family; he kept my mother near breakdown for much of their married life; but he rescued me from a teenage trauma by taking over my newspaper round; and he drove me out time after time to see the birds that I (with his early encouragement) lived by; and he was a terrific grandfather too for my two older sons when they were at primary school, playing football with them every week, having recruited them to help (as bag carriers etc.) with his own overflowing storage unit, and then, after such exercise, rewarding them with heinously over-salted scrambled-eggs for tea.

Both boys, now men, recalled the saltiness at the memorial service my sister and I were finally able to hold for our parents in March 2024.

The scattering (in Somerset and for the radio) has been my work and is particular to its particulates – my dad’s – but almost everyone I know around my age (some younger and older people too) seem to have some ashes of a loved one to scatter or have done some scattering in the recent past. Getting rid of the remains of relatives and their material stuff is, it can seem, what most people in their sixties do most of the time these days. Mourning a loved one can be terrifically sad and clearing their house an exhausting wrench but there is, in such grief-work, a coming to terms with life which must be good to have. We seek closure in our dealings with our people as well as being able to shut the door on the houses where they lived.

Letting go is where it’s at. That’s what I learned from my dad.

There isn’t much rubbish left over behind a radio programme. It goes out, on the air, and must make its way there. Scattering – our programme – is a broadcast about a broadcast. A sowing and a harvest at once.

Catch it if you can.

*

‘Scattering’ will be broadcast this evening at 19:15, and available to listen back to on BBC Sounds thereafter.

*

Tim Dee was a radio producer at the BBC for the best part of thirty years and is also a writer; ‘Greenery’ and ‘Landfill’ are his most recent books. He has been a regular contributor to Caught by the River, most recently offering his Shadows and Reflections for 2024.