In an essay written to accompany Richard J. Butler’s paintings of Naxos, Rob St John considers the artist’s micro-topographies — drawn from landscapes both material and imagined.

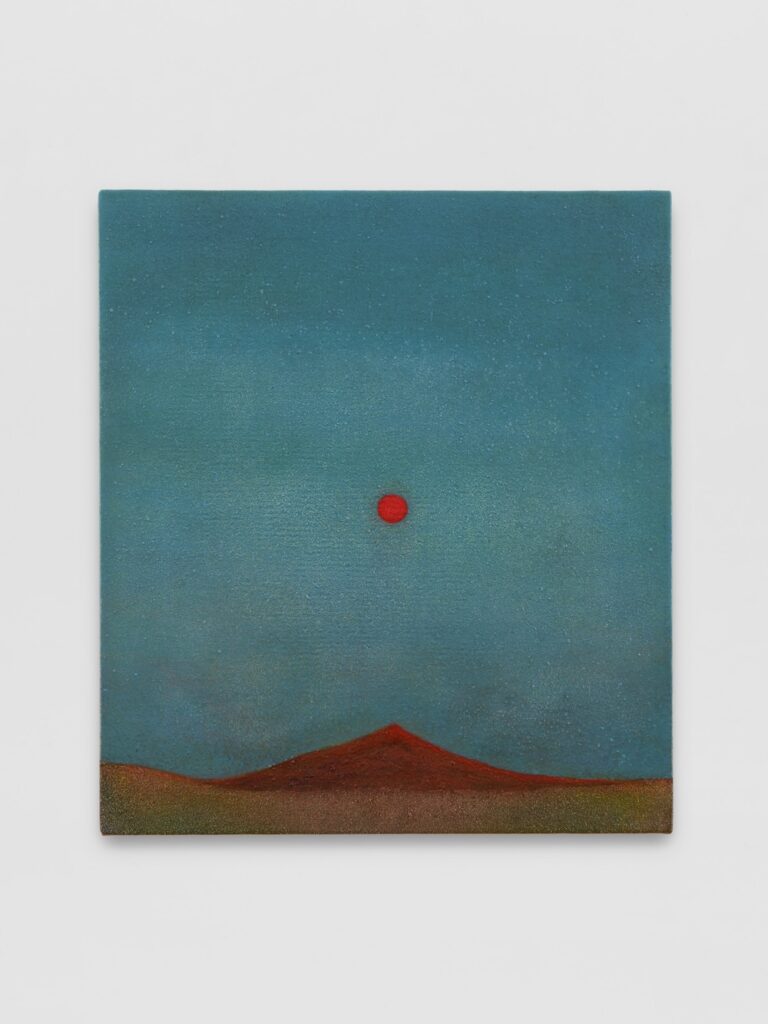

‘Red Mountain’, courtesy of Canopy Collections. Photography by Ollie Hammick.

“Greece is a good place / to look at the moon, isn’t it / You can read by moonlight / You can read on the terrace / You can see a face / as you saw it when you were young.” – Days of Kindness, Leonard Cohen, Hydra, 1985

Islands have long figured as sites for artists to document and reshape their experiences of shifting environments. Islands have also often been places of experiment, where geographical isolation has given rise to new forms of ecological and cultural invention. The edge effects of an Anthropocene age – the strange new inorganic geological strata, the gusting of increasingly extreme weather events and the endless creep of sea level rise – are often felt first, and most intensely, on island shores. Island eyes are so often drawn to the sea, where the boundaries between land, water and sky dissolve into one another.

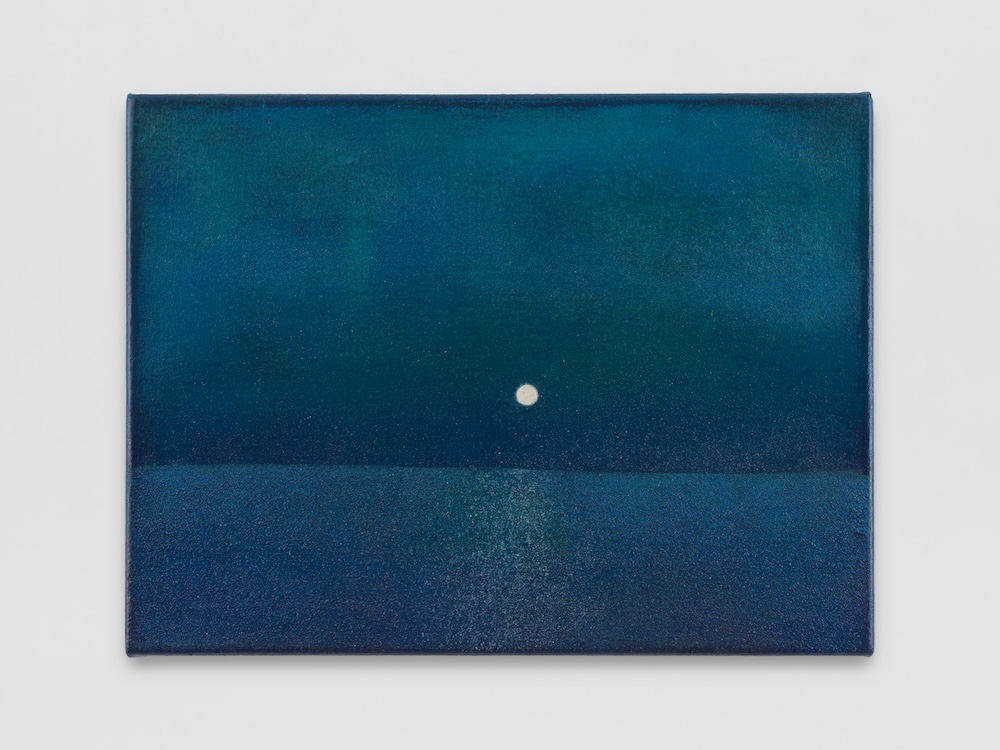

Richard J. Butler’s series of eight paintings from the Greek island of Naxos glow with a strange sense of place drawn through such island imaginations. Butler’s horizons – formed through micro-strata of grated pastel, acrylic gel and paint – are populated by celestial bodies, floating mountain ranges and clouds of light. Each sit within shimmering colour fields which appear to stretch scales: familiar forms which appear dislocated out of time.

‘Ocean (full moon)’, courtesy of Canopy Collections. Photography by Ollie Hammick.

The works were made in August 2024 during a residency at La Chapelle Saint-Antoine on Naxos. The island, located in the South Aegean Sea, has a rich history of geological materials. White Naxian marble has been quarried for millennia for use in sculptures and buildings at ancient Olympia and the Athenian Acropolis. Shards of the island’s deposits of emery – a granular rock widely used as an abrasive – appear as landscapes in miniature, run through with topographies of orange, blue and sapphire corundum.

Butler’s process on Naxos reflects the island’s geological understories. Working in a white-washed chapel weathered by the elements, he built up layers of grated pastel which were then drawn and erased into place on his canvases. The sea horizon of one painting, Ocean (full moon), glimmers in deep indigo, punctuated by the marble-white glow of the moon. Another painting, Stratum, glistens like the opened face of newly-upturned ground, as a hazy moon rises through waveforms of cadmium red.

During his work, coloured pastel shards and dust accumulated amongst the debris blown in from the outside world onto the chapel floor, and were subsequently swept up, collected and catalogued. These material palettes – a mixing of inner and outer worlds – were sorted into jars and re-used, both on the paintings, and on a series of monochrome marbles. These four softly-geometric objects were created by gradually applying the pastel dust from the chapel floor to fragments of pure white Naxian marble left behind by a previous resident. The marbles tie Butler’s work in the chapel to wider creative geological practices on Naxos: miniature sculptures formed through material layering and accumulation.

It’s here that Butler’s practice channels the influence of mid-20th Century archaeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes. Published a month after the opening of the Festival of Britain in London, Hawkes’ 1951 book A Land is a deep-time daydream charting an alternative history of Britain formed by repeated human migrations shaped by environmental shifts and geological upheaval. Butler’s repurposing of Naxian dust and debris in his pigments is at once acutely site-specific and abstractly universal, drawing on Hawkes’ evocation of geological strata as the layerings of organic and inorganic material which underly the formation of societies and cultures. Here too, in the soft uncanny shimmers of Butler’s pigments we see Hawkes’ notion of land brought into an Anthropocene age. Doubtless, flecks of microplastics and synthetic compounds were blown into the chapel across a long ocean fetch of wind currents, adding human-made components to Butler’s pigments: a strange, new form of elemental palette for an unsteady, hyperconnected world.

‘Rainbow’, courtesy of Canopy Collections. Photography by Ollie Hammick.

Butler’s work also resonates with longer histories of modern painting and Romanticism in Northern Europe. His Naxian paintings slip between figuration and abstraction in offering a more-than-representational sense of the landscape. They depict a place that is many places at once, and extend an invitation to linger: to wander and wonder through micro-topographies of pastel and pigment. Butler draws on art historian Robert Rosenblum’s identification of a lineage between Caspar David Friedrich’s luminous paintings of the sublime, through J.M.W. Turner’s elemental reshaping of light and energy, to contemporary Abstract Expressionists including Mark Rothko and Georgia O’Keefe. Writing in Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition (1975), Rosenblum suggests that these artists share a kinship in the “isolation of nature’s primordial elements… within more abstract vocabularies.” (1975, p.12)

Butler’s series of paintings are formed from an island imagination within this lineage, where his attention was drawn to geological and meteorological patternings of his Naxos chapel, refracted through childhood memories of his Yorkshire landscapes of home. For Butler, “The meeting of sea, sky and land becomes the embodiment of place,” meaning his paintings are less the representation of a fixed viewpoint, and more a channelling of the weave of the world. Paintings less from nature than as emergent natural forms themselves. It’s here that Butler’s work resonates with feminist theorist Elizabeth Grosz’s (2008) notion of ‘the frame’, a concept of creative practice as a joining with the chaos of more-than-human worlds.

A symbol in the sky – a moon, star or cloud formation – acts as an anchor to such forces in each painting. These celestial bodies draw the gaze from the celestial to the universal, from Mediterranean islands at the front-line of the climate emergency to abstracted memories of Northern English landscapes. These are scenes without human presence, inextricably linked to the material and imaginative landscapes of their creation. They are illusions of balance and peace formed through temporary stillings of a world made increasingly strange: scenes that Butler says could be at once, “from the present, the distant past or a potential future.”

*

Richard J. Butler’s solo show ‘Naxos’ is on display at Canopy Collections, London WC1A 2QA, until this Friday, 28th February. More information here.

Rob St John is a writer and artist based in Lancashire.