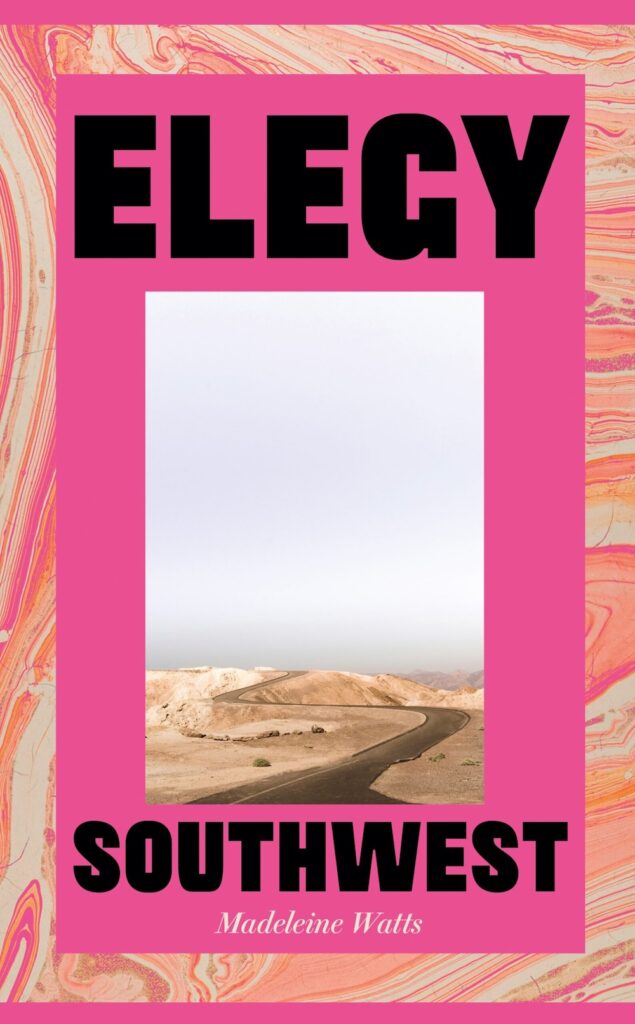

Against a backdrop of climate change, Madeleine Watts’ ‘Elegy, Southwest’ is a lament for a world, a relationship, and the American road-trip novel, writes Abi Andrews.

The ‘elegy’ in the title of Madeline Watts, Elegy, Southwest is several. This novel is an elegy for a world, a relationship, and also a form: that of the American road-trip novel — its depiction of velocity and limitlessness hitting differently now, backgrounded by climate change. Watts presents the effect this change has on our cultural image of the western states — the specific desert-road setting recognisable to all consumers of American culture, clashing now with a contemporary environmental one.

The novel follows a young married couple, Eloise, an academic with a fascination with the Colorado river, and Lewis, who works for an arts foundation. The Colorado river itself acts as a metonymy for the contemporary climate emergency; Eloise traces the history of its damming to support the mega-cities of Las Vegas and Phoenix and LA, to the threat that now looms, with the reality that its water is running out. Also looming are the crackling fires which that dryness promotes — the novel is set in 2018, the year of the Camp Fire, the most destructive wildfire, so far, in California’s history. The fire and the river are agents that lurk in the background of their trip, threatening to impinge on the narrative. A great success of the writing here is the way in which it taps into our predisposition to pathetic fallacy — looking for literary signs in the weather — causing discomfort as it situates us in the context of climate emergency, where the weather has become so hostile and unpredictable, and so relentlessly ominous.

The characters face this with denial and a tragic perseverance, driving along highways according to Eloise’s itinerary, to their pre-booked motels and airbnbs. Their trip is antipodal, an inverse of what we anticipate of a road-trip narrative — where we might expect characters to experience self-discovery, fall a little more in love with themselves and the world — and its inversion is caused by the infringement of the changed landscape onto a dream of an older America. The dream we are called to recognise is one detached from landscape, or hovering slightly above or outside of it, where the view is almost always from the road, the diners, the motels. When Eloise and Lewis travel into the natural landscape, they are often uncomfortable and unnerved; the landscape is a threat towards the western dreamscape they persist at. And this persistence at a dream is mirrored in their deteriorating relationship, as they attempt to weather the grief of the death of Lewis’ mother.

Eloise is confronted by the possibility that the grief will not develop in definable stages as she had been taught to believe, that instead the grief will unfold in haphazard and unpredictable ways. The behavior of their grief mimics the volatile climate, likewise threatening to make the roadmaps obsolete. Like the obstinate water fountains Eloise worries over — running in municipal parks while the water table diminishes — their relationship persists into the uncanny acts of the road-trip genre, with the apprehension that at some point, the water will run dry. Watts seems to play on the uncomfortable and inevitable impulse of aestheticising disaster, in the disintegrating relationship that is hard to let go of because it still has glimmers and sparks that might yet erupt, which is like a sunset polluted by wildfire — uncommonly beautiful in part because of its novelty; both foreboding and sublime.

The simultaneity of acceptance and refutation in our responses to the climate emergency is suggested in Eloise’s reaction to her own suspected pregnancy. She retains an impressive ability to deny her own self-knowledge, not acting even as things go amiss with her body, protecting herself with denial. Her undecided feelings toward the latent potential of a pregnancy speaks to the ambiguity central to our time, of a future that might or might not not be desirable or even possible. Eloise’s detachment is painfully familiar and general: “Maybe nothing very bad was happening, had happened, was still to come; how could I even discern the edges of the event?”

Mostly things are not said between Lewis and Eloise, instead buried down like the spent uranium in the landscape, threatening to become quietly abortive. Unspoken dread is where Watts excels — drawing out a slowly accumulating emotional intensity — even if at times the lack of emotional climax or resolution, and the detachment of Eloise from what is happening to her, might leave a reader thirsty. But isn’t that accurate to the ambiguity of living with not-always-quite-definable or pinpointable change? Elegy, Southwest causes us to sit with ambiguity, trialing mechanisms for surviving something that may have no peak or resolution, living through the suspense of calamity to come.

*

Published by Pushkin Press, ‘Elegy, Southwest’ is out now and available here (£18.04).