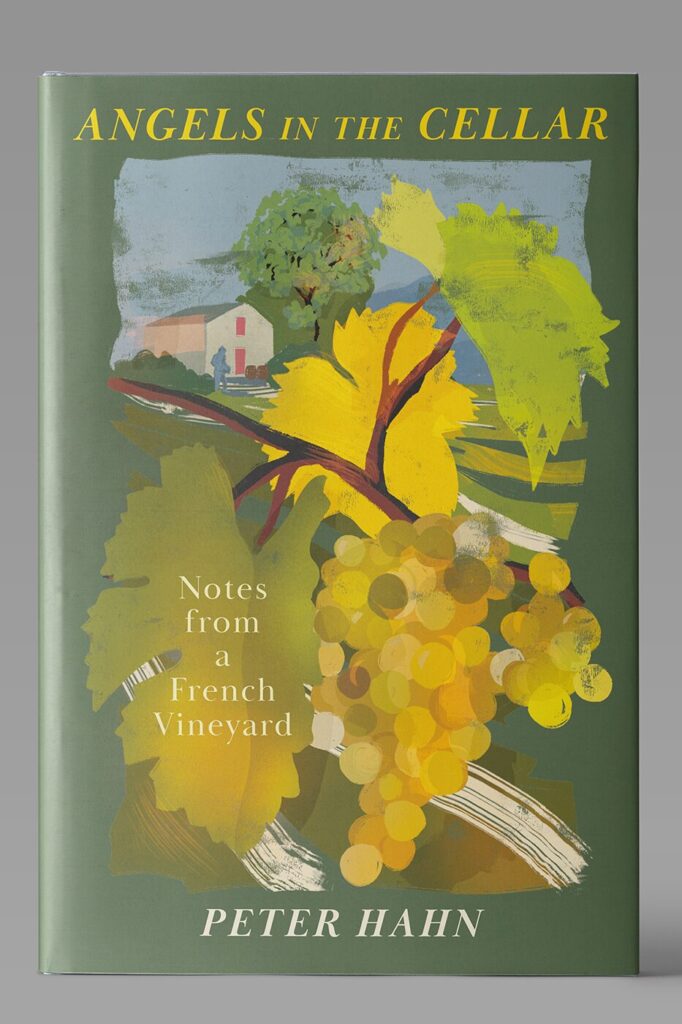

More than a description of wine making, Peter Hahn’s ‘Angels in the Cellar’, recently published by Little Toller, is a celebration of nature and a love of the land, the seasons and the soil, writes Paul Bursche.

There is a word in the Celtic languages that I love, for both its sound and its meaning. In Welsh it is hiraeth, in Breton hiraezh. It describes a feeling of nostalgia or yearning to go back to a home or a place that you can’t return to, because either it no longer exists or it never existed in the first place. It is both the real and imagined bond we feel with a landscape, a time, an era or a person. This is how I felt. I knew there was a place I was longing for. But how was I supposed to find it if I could no longer return there or it never even existed?

Twenty years ago, American Peter Hahn, a successful corporate executive working in finance, felt himself starting to have a breakdown in the back of a London cab. Emotionally exhausted, he realised the only path forward for his sanity was a complete change and so he embarked on starting a new life as a winemaker.

Eventually he found his way to Clos de la Meslerie, a 25-acre plot in the Loire Valley with ten acres of ancient vines and a crumbling farmhouse, to which he relocated with his family and dedicated the next two decades to regenerating. His dream was to establish a small-scale, organic winery run in the most sustainable way possible.

In the two years it took for the sale of the house to go through, Hahn went back to college to get a viniculture degree and worked as an apprentice on neighbouring farms. He was soon taken under the wing of two local and highly respected winemakers, Vincent and Damien, who in turn realised the American was completely serious about his decision to do as much as possible by hand and by traditional methods. It took several years to breathe life back into his tiny domaine as two decades of conventional farming had sucked the energy from the soil and the environment, but he persisted. In 2008 his first Vouvray Clos de la Meslerie was released and has always sold out since, winning many awards along the way.

Angels in the Cellar – his story — takes us through a year in seasons on the vineyard as he reflects on his methods, story, and the lives of the people he now lives amongst, including his wife Juliette and family, his once dubious French neighbours – now friends, and his ever-changing seasonal workers, drawn from eastern European countries and those fleeing war in Ukraine. The book sets out the natural rhythms of the production of his award-winning Chenin Blanc, from the pruning and shaping of the vines in the winter through to the harvesting in the autumn and the resetting for the next year.

There is deliberately very little modern equipment at Clos de la Meslerie, from the near hundred-year-old basket press Hahn was able to restore, to hand-held vine cutters and manual pumps, everything is done with as little mechanisation, the fewest chemicals used, and the lightest touch as possible. This, of course, creates a great deal more work but he seems to revel in this, as in this description of hand-pruning and shaping the vines in the winter:

Pruning is deliberate, repetitive and unhurried. I need to pace myself because on every acre of this vineyard there are over 2,500 vines, making for a total of close to 24,000 individual plants. And I will need to take care of each and every one of them, looking closely, taking stock before a single cut is made, before I carve each one for the next growing season. Pruning is all about making decisions. Taking into account a plant’s strength and vigour, its age, even its position in the vineyard, I shape the vine according to how many bunches of grapes I think it should grow in the months to come. It’s the moment when I make a choice about the quantity and quality of the grapes I am asking the vine to give me. And I resist hiring people to do this job with me, because it’s perhaps the most important and rewarding activity on a vineyard. Every year, without fail, pruning teaches me to live in slow motion.

Each stage in the process of winemaking is described as carefully as this, from the choice of the oak barrels and the fermentation process, to how he hires horses to till the land in between the vines, to the bottling of the new vintages, and how he and Juliette lay the bottles down in their cellar each year and choose classical music to play to them. The language is detailed and precise, and in its precision is a kind of poetry that sucks you into the pages and helps one understand the wonder that Hahn has found in his new life.

The story is far from halcyon. The countless challenges around the farm and the house, the sheer back-breaking and painful nature of year-round manual labour — ‘The number of cuts, gashes and bruises I have sustained is countless’ — together with their increasing concerns about crop risks in a changing climate are described in compelling detail too.

Early in the book, Hahn’s French neighbours spend a dinner trying to dissuade him and Juliette from taking on the hard life of winegrowers. And later Hahn tries to put off a visitor to his vineyard who wants to do it for himself too, as he acknowledges that ‘If I had known then what I know now, I probably would not have done it. So I’m very glad that I didn’t know then what I know now.’

But he did do it – and this book is more than a description of wine making, it is a celebration of nature and a love of the land, the seasons and the soil, and how these things can nurture the soul.

*

‘Angels in the Cellar: Notes from a French Vineyard’ is out now on Little Toller.