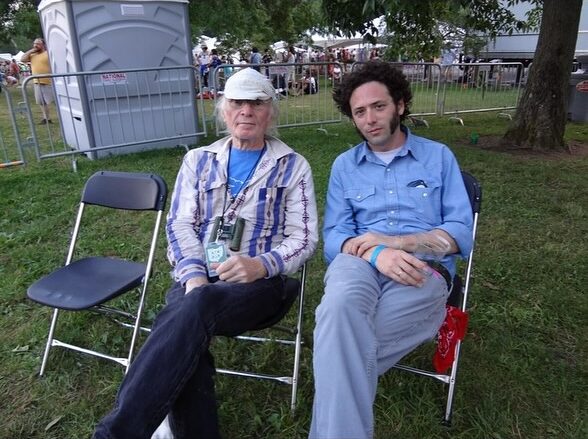

Jerry David DeCicca pays tribute to the singular folk musician and artist Michael Hurley, who died last week aged 83.

I played my first gig with Michael Hurley in a pizza parlor in Bloomington, Indiana called Bear’s Place. Michael was living in Portsmouth, Ohio, a river town two hours from me in Columbus, Ohio. This was 2002 and I hadn’t made any records yet. When I tried to book the Bloomington gig, the promoter asked me if I knew Michael, since he heard that he was living regionally. I had met Michael just once, in a bagel bar after one of his shows and, for some reason, he gave me his phone number. I exaggerated my relationship to the promoter. He promised Michael would get $300 and I could keep the rest if I could rope the elusive legend onto the bill. I called Michael, using his phone number for the first time, and, for some reason, he agreed. This was the beginning of knowing and not knowing him, a story many people share with as much joy as I do.

When I pulled up to the bar with my bandmate, Noel, Michael was already there and inside. His baby blue station wagon was a can’t miss in the parking lot. I looked in the back seat and saw the master tapes for Armchair Boogie. His car doors were unlocked (I checked).

With a couple hours before the gig, we drank beer at a table in the empty, dark room, Michael’s back to the bar. The phone rang and the bartender called out, “Is there a Michael Hurley here?”

Michael didn’t turn around. The bartender called out his name again. Michael still didn’t move.

“Michael?” I said, wondering if he had trouble hearing, “I think you’ve got a phone call.”

“I know who it is.” Michael told me, ignoring his name. He said a promoter from St. Paul, Minnesota was looking for him because he was supposed to do a gig there in two days. He said he wasn’t going because he’d decided to judge a pie competition in West Virgina instead. But it wasn’t a community event in a small, rural coal-mining town with rows of homemade baked goods as you might imagine. It was just three women who invited him over to one of their houses. Pie and women were not themes in only his songs.

There were only 8 people at the gig that night. After it was over, the promoter handed me $35 to give to Michael. It was all the money there was. I was deeply embarrassed to hand it to him, feeling like he had trusted me, and I let him down. But Michael took it on the chin and didn’t make me feel bad.

Every gig I saw Michael do was beautiful, and I saw many over the next couple years. The best gigs I saw were around 2004 at a BBQ restaurant in South Bloomfield, Ohio, back then a four stop sign town of about 1000 people. Michael would play there every few months rotating between fiddle, guitar, a keyboard, and fretless banjo for hours as people ate ribs and drank. He’d play his own songs, but also ones by Merle Haggard, Dwight Yoakam, and Tom T. Hall. He was background music, except to a couple people like me who sat in awed enjoyment. I’d run into him at parties and shows, but it was hard to connect to him with other people around.

It wasn’t until we played together in Seattle on Super Bowl Sunday in 2005 that I knew he had left Ohio for the northwest. He never mentioned moving in his emails.

One night in 2007, my phone rang and it was Michael. When I heard his voice, I thought he was calling to discuss the gig we were supposed to play in New York at the Cake Shop. Nope. This night, he was in Lancaster, Ohio at a Burger King. He needed me to pick him up right then and take him to the airport the next morning. When I pulled up, I could see him through the window, just sitting there, no one else in the place. I wasn’t sure how he got there, but he was upset that it took me an hour to fetch him even though I was 40 miles away and I was still 5 minutes earlier than I told him I’d be. On the way back to my place, we stopped at a bar to get something to eat, but he wasn’t drinking then. I had a couple beers as he pounded glasses of iced tea. He had been dry for a few months and was now heavily caffeinated at 10pm. Back at my apartment, I made up the futon, but he wasn’t tired. He kept me up for hours, as he flipped through all my records with running commentary (he loved Jesse Winchester, Nanci Griffith, and Phoebe Snow). He told me everything about his life from birth to the present without me asking many questions to prompt him. If I had to choose one conversation in my life that I wish I had recorded that would have been it. Two weeks later, I received a postcard from him. He shared that it was a meaningful hang for him, too. For as cagey as Michael could be, he could also be very sweet, sincere, silly, and deep, just like his gorgeous music, that made you feel like you were a part of his songs.

Last year, he read me a few paragraphs from the memoir he was working on. It had the cadence and nuance of literature but also sounded like him talking. But then he said he’d stopped working on it and didn’t want to give me a reason why. I feel lucky to have known him, for minutes and hours and days, bits here and bits there, over the last couple decades. It’s incredible to think how one person can be so singular to so many people.

Michael Hurley, 20th December 1941 – 1st April 2025

*

Jerry David DeCicca’s new album, ‘Cardiac Country’, comes out on 25th April via Sophomore Lounge records. It features BJ Cole on pedal steel and includes the song, ‘Good Ghosts’, about finding truth and companionship in the records of singer-songwriters that have passed on. He’ll be performing with Bill Callahan throughout Europe this summer.