‘Man In A Macintosh’ – Iain Sinclair tells the story of his quest for knowledge of a lost literary Londoner, from todays Guardian review. Get the paper itself if you’re not too late as the piece includes a portrait photo of the subject, Henry Cohen, in which Sinclair describes brilliantly as having, “…(the face of ) a cinema organist after the coming of sound”;

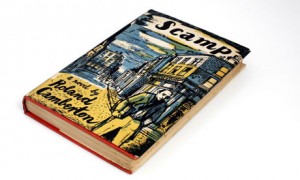

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but it’s not a bad place to start. The design of the fiction put out by John Lehmann in the late 1940s and early 50s had the louche swagger to complement an edgily cosmopolitan list: Jean-Paul Sartre, Saul Bellow, Gore Vidal, John Dos Passos, Paul Bowles. You could smell fierce French tobacco lingering on tanned pages and sample exotic locations filtered through fugues of premature sex tourism. The books looked good enough to frame, we took the contents on trust. And being by 1975 a trader in forlorn and forgotten literature, I slid copies of two London novels published by Lehmann under my stall, in the fond belief that the John Minton dust-wrappers would give them a market value at some unspecified future date.

The novels were credited to someone called Roland Camberton. I set them aside: until the time was right to make the discovery that the most exotic location of all, the true heart of darkness, was on my doorstep in Hackney; a slack-waisted borough of which Camberton was the unrecognised laureate. Despite the gentile surname, he wrote within a recognised Jewish tradition: the unsentimental education, the investigation of a wider city and the breaking away from the clinging embrace of an orthodox family. Rites of passage involved expeditions to the real East End, before sticky experiments with Soho cafés and clubs. Versions of this story with greater or lesser degrees of cynicism and panache would include Simon Blumenfeld’s Jew Boy (1935), Alexander Baron’s The Lowlife (1963), The World is a Wedding (1963) by Bernard Kops, Emanuel Litvinoff’s A Journey Through a Small Planet (1972) and even Harold Pinter’s The Dwarfs (1990). Naturally, the authors denied any familial connection and dismissed the lesser titles in the series as incompetent, fraudulent and not worth 10 minutes of any serious reader’s time. Baron, more generous than the rest, was interviewed by Ken Worpole as background for Worpole’s first book, Dockers and Detectives (1983). The Hackney author moved the discussion straight back to Lehmann. “The people you speak of were all discoveries of John Lehmann, a part of his attempt to find a proletarian literature. This had its condescending side. There is, from Lehmann and his ilk, a homosexual attitude to the working class.”

Litvinoff confirmed this accusation when I talked to him for a film on submerged London writers in 1992. He recalled being invited, when still in uniform and heavy boots, to Lehmann’s elegant flat, where the publisher was waiting, draped in a Noël Coward dressing-gown, drink in hand. There was a vampiric thirst for fresh blood, hard male prose, the subterranea of the city. Lehmann had other sources of income, shadowy business interests; publishing was a superior hobby, a way of meeting interesting young men. Much of the zest in English fiction comes from rogue individualists looking for new ways to lose money by leaving orphaned books for future scavengers to discover and promote.

One of Lehmann’s tricks was to pair off a modest working-class writer with a posh but troubled artist such as Minton. The zones where the tribes collided, in apocalyptic blind dates, were Soho and Fitzrovia. Moneyed dilettantes, professional scroungers and the thirsty dead: shoulder to shoulder, they fought for space at favoured bars. They worked much harder than nine-to-five civilians to promote their own legends, to the point where some other mug would write the book for them. The point, as Dylan Thomas and Julian Maclaren-Ross soon learnt, where you become an actor in the anecdote of a rival is the point where your words are no longer required. It’s time to disappear. To play the final card: suicide by other means. The last train to the suburbs. Stiff nights on the bench in the Russell Square Turkish baths. Trembling hands failing to get cold coffee, unspilled, to scabby lips. Late-bohemianism is a career better recollected than experienced.

Scamp, published by Lehmann in 1950, is Roland Camberton’s first novel. It is set in Soho, Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia; in the rented rooms, pubs, all-night cafés where the author could well have come across Minton and certainly did lurch against Maclaren-Ross. Ivan Ginsberg occupies a rat-infested bathroom-kitchen, while trying to scam the funds for a stillborn literary magazine. The cancelled cheque stubs of Camberton’s own life are an audition for the real business: the manufacturing of fiction.

“Ginsberg found himself confronted with the type-writer . . . A story a day, that was his minimum task; two thousand words, preferably with a plot, development, a climax, and a twist. After six months of this routine, he was beginning to feel an intense hatred of the short story, in fact, of all writing. What an abominable occupation it was!”

Camberton’s prose is feisty, but there is something fugitive about the Hackney writer: if he has broken away from his roots, he knows they will reach out to choke him. The novel is heady with the delusion of freedom, but it’s on parole. Delivered like an over-researched thesis, Scamp is quietly triumphant about coming into existence, but crushed by the horrible labour of composition. Nobody wants a new recipe for oblivion.

Maclaren-Ross reviewed Scamp with withering condescension: “Mr Camberton, who appears to be devoid of any narrative gift, makes this an excuse for dragging in disconnectedly and to little apparent purpose a series of thinly disguised local or literary celebrities.” One of whom, although he doesn’t mention it, is Maclaren-Ross himself, lightly disguised as the “former commercial traveller” Angus Sternforth Simms. “That he found time to write at all puzzled the little crowd of habitués which watched him and heard him every evening, with respectful animosity, at his corner of the bar.”

Other notices were more encouraging. Scamp won the Somerset Maugham award for 1951. Camberton was invited to the Ritz to be inspected by his lizardly benefactor. A friend wondered how they had got along. “Oh, marvellous,” Camberton reported. “He asked if I wanted tea or whisky. And I said whisky. Maugham said, ‘That’s right, good show! I’m going to have both.’ And then we put English fiction to the sword.” Maugham left the judging of his prize to a committee. Kingsley Amis, the winner in 1955 and the dominant voice of his generation, was a writer against whom the old man nursed numerous prejudices. ‘Boorish and provincial,’ he said to Camberton: but, all too soon, the author of Scamp was drifting out of print and into Grub Street anonymity.

The second book is always hard. Camberton, in choosing to set Rain on the Pavements (1951) in Hackney, was composing his own obituary. Blackshirt demagogues, the spectre of Oswald Mosley’s legions, stalk Ridley Road Market while the exiled author ransacks his memory for an affectionate and exasperated account of an orthodox community in its prewar lull. Competing voices shout across a crowded kitchen where loyalty to family battles against hairball claustrophobia. The novel unfolds through a sequence of discrete but connected short stories, which fade away into sudden darkness; an untimely return to Poland, erasure, silence.

I suspect that the character of Uncle Jake is a refracted self-portrait by the author. A midnight cyclist and compulsive autodidact, Jake wobbles between ideologies, short-lived enthusiasms. He taps on his nephew’s window, asking to share the narrow put-u-up bed. Like Camberton, Jake decides to join the Royal Air Force. He has to get away from everything that makes him what he is.

“The family realised that the mystical cord which, for all his eccentricities, bound Jake to them and to all that was reasonable and normal, had snapped, cruelly, inexplicably, and unnecessarily. Jake was, voluntarily and alone, descending to the lowest section of society; he was going to become a homeless casual labourer, a tramp, a criminal even. A young man who had no money, no job, no home, no wife, no friends, was, in essence, a criminal.”

Jake’s guilty secret is that, without letting friends or family know, he has published a novel. And its title is: Failure. There is a schizophrenic moment when David Hirsch, the narrator, opens the book written by Camberton’s alter ego: “With what strange feelings David opened the thin, ill-printed, yellow-wrappered volume. It was as though the past itself had been drawn, temporarily but without noticeable change, from the vaults of the museum.”

Then Camberton vanishes, nothing is heard from him again; he publishes no third book. Minton’s dust-wrapper for Scamp takes on the jaundiced colouring of the uncut pages of Failure. A balding man, left hand in pocket, right hand gripping a furtive typescript, slouches down the cobbles; past the pub, out of the frame, into the wilderness.

I asked Patrick Wright, who had befriended Litvinoff and written very effectively about his work, what the acerbic old man felt about Camberton. “He was totally dismissive,” Wright said. “Those two books, Litvinoff reckoned, had nothing to do with the East London he had known as a young man. They were opportunistic, banal. He preferred to remember Wolf Mankowitz. Now there was a man who knew how to make money.” As to Camberton’s later career, Litvinoff thought he had spotted him once, going into the offices of the Reader’s Digest, but he couldn’t be sure.

Baron, put by Worpole to recalling the “Jewish East End writers” of his acquaintance, finished with the Litvinoff brothers. And then, after a long pause, he mentioned one more. “Oh yes, I’d almost forgotten him: Roland Camberton. I saw him once at a party. I think, like Pinter and myself, he went to Hackney Downs School. I can’t remember whose party it was, except that it was somewhere in St John’s Wood. I didn’t venture very often into these exotic territories. I had this little uneasy chat with Camberton, a strange man. That’s it. That’s all I know.”

And there it would have finished, with no more information than you could retrieve from the flap of one of Camberton’s novels. Born in Manchester in 1921. Brought up in London. Served in the RAF as a wireless mechanic. Worked as teacher, copywriter, translator, tutor, canvasser, publisher’s traveller. A future project, an autobiographical book called Down Hackney, is floated. But nobody I have spoken to has ever seen a typescript.

The nagging mystery was one of many I worried at, up to the point when I started work on my own memoir, a documentary-fiction called Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire. I projected a connection with the author of the book-within-a-book, Failure. Camberton’s topography, his questing excursions, haunted me, becoming, in their fashion, a kind of model. “It was necessary to know every alley, every cul-de-sac, every arch, every passageway; every school, every hospital, every church, every synagogue; every police station, every post office, every labour exchange, every lavatory; every curious shop name, every kids’ gang, every hiding place, every muttering old man . . . In fact everything; and having got to know everything, they had to hold this information firmly, to keep abreast of change, to locate the new position of beggars, newsboys, hawkers, street shows, gypsies, political meetings.”

Amen! Huzzah! My mad creed in a single paragraph.

Having absorbed Hackney, its lost rivers, demolished theatres and built-over market gardens, Camberton’s continued existence was tautologous: he had become the spirit of place. And through place, miles walked, he was to be recovered. Or so I excused my failure as literary snoop, uncommissioned private eye. Until, in the most unexpected way, the name of the vanished writer jumped out at me. A slender booklet, Walking the London Scene (Five Walks in the Footsteps of the Beat Generation) by Sydney R Davies, dropped on my doormat. Here was permission for a jug of coffee and a rest from my researches. I followed with interest the story of how a person called Douglas Lyne, described as an “archivist and Chelsea habitué”, met William Burroughs. They drink together. Lyne lends Burroughs a pound. Returning from Tangiers, the notorious junkie repays the loan. A line of double brandies is fired back in celebration. When the two men meet again, in a pub called the Surprise, they are joined by a third: Henry Cohen. Lyne decides that they will go back to his flat and make a recording on a creaking reel-to-reel machine.

They are now, all three, quite drunk. The man from the pub, Cohen, the one who will operate the recording machine, was himself, years ago, a published writer. That might have been the source of his irritation. His books were classically constructed, widely reviewed and completely forgotten. To hide the shame of his alternative career from his strictly religious family, Cohen took another name: Roland Camberton. This Chelsea night must have been one of the most fantastic conjunctions in literary mythology: like a posthumous nightmare for Maugham. Burroughs, the hierophant of fractured modernism, interrogated by a champion of the local, the specific, Hackney picaresque.

Naturally, I had to track down the tape. It became a grail, all of my interests converging on a single elusive object. I made contact with Davies and he arranged a meeting, south of the river, a long way from Chelsea, at the house where Lyne now lived. Lyne was a person adrift in memory, calling up anecdotes of military life, intertwined with genealogies of the Welsh Marches and musings on the rogue priest, Father Ignatius, who raised a girl from the dead in Wellclose Square. He was a charming and discursive anecdotalist, the years in pubs and clubs had not been wasted. He wouldn’t be deflected, by my Camberton probings, from the unravelling of an invisible thread. There were mugs of slow tea and many chocolate biscuits. Lyne, with his swept-back silver hair, trim moustache, milky eye, was like a benevolent General Pinochet.

Roland Camberton – or Henry Cohen, as he had known him – was one of his closest friends. Lyne moved in the post-war Soho world of documentary films and drinking clubs where he mingled with writers, painters, adventurers on the lookout for new islands. “Johnny Minton was one of us. He did the covers for Henry’s books.”

The first meeting between Lyne and Cohen was in Chelsea at the Pier Hotel. “All the local mandarins were lolling about,” Lyne told me. “Dregs and real dregs. With the great Henry. Who was an extremely distinguished-looking Jewish man. Like a great composer. Huge brow. We drank and we chatted away. We bought – it must have been me – a bottle of wine. And we went back to Henry’s room. He said: ‘I’ve just won a prize. Somerset Maugham has given me £500.’ Maugham thought Henry was a good storyteller. And he was right. Henry could do colourful characters. He had great warmth. He loved listening to what you had to say, but he didn’t like wasting his time doing practical things.”

And so, inch by inch, a narrative of the lost years was teased out. Cohen learnt to write in the air force. “When I had a spare moment in the office,” he told Lyne, “I would scribble bits and pieces and read them out at lunchtime and see who laughed at which passage. I was quite surprised, they liked my stuff. But the bits I liked they found high-fallutin’ and boring.” Coming across an article by Lehmann in which he said that he was searching for English authors with the urban fizz of Saul Bellow, Cohen decided to make an approach. He took his RAF gratuity and moved west. “I was spending all my time in Soho. Living it up as far as I could. Drinking. Courting the girls. I’d come from a stuffy orthodox Jewish background. I found Soho life fascinating and I thought other people would want to hear about it. I wrote Scamp. And I remembered John Lehmann.”

After Scamp, there was talk of a film. But nothing happened. Cohen produced some journalism for trade magazines. He kept his head resolutely down. “You couldn’t say that’s what Henry was doing, freelance journalism,” Lyne reported. “You couldn’t ask. Henry wasn’t a man who did things. He just ran out of ideas. I should have learnt more from him. I didn’t take him seriously. I think he had an interior purpose. He hated to be known. He was a very secretive person.”

The pseudonym Cohen adopted was resolutely non-Jewish. He cast himself as a matinée idol rescued from some forgotten Hollywood programmer witnessed at the Clarence in Lower Clapton. Ronald Colman, Madeleine Carroll and Roland Camberton in The Prisoner of Zenda: such was the fantasy. The reality of this grubbing, scratching postwar era was membership of a literary underclass described by Maclaren-Ross (in a letter to Lehmann) as being made up of those who “live like rats among the ruins which they themselves have helped to honeycomb”.

The family didn’t give up on the decamped eldest son. Lyne remembers an afternoon in his studio flat. “This very Hatton Garden sort of chap came around. He had a set of sacrificial knives which he used for cutting animals’ throats. Henry jumped up. ‘This is my brother.’ The brother said: ‘I’ve come to bring you home to Hackney.’ Henry told me that the same scene happened every week. His father was ill.”

Lyne got married, changed pub, lost touch with his friend. Years later, in Soho, he bumped into Henry again. “He was with a very attractive woman. I think he must have been knocking about with her for quite a long time. She was very gentile, very county. Enormously devoted to him in a distant kind of way. She didn’t like being associated with Soho or drink.”

Cohen said that things were going rather well. “She’s got lots of money. She wants to get married. She’s got a house, with hunting and that kind of thing. I go down there. My family have cut me off, they don’t want to see me. I can’t go on. I don’t really have anything to do.” Roland Camberton had grown into the situation that befell Uncle Jake in the novel written so many years before. “He lost touch completely with the family . . . their relationship was quietly wrapped up, as it were, placed in the cupboard of limbo, and locked away.”

Ducking and diving, Cohen had the painful task of reading other people’s novels for MGM: could they be turned into films? He brought Lyne onboard – and Lyne, in return, set Cohen up with a trial, writing copy for EBIS (Engineering in Britain Information Services). “What’s this fellow done?” said the boss. “A picaresque Soho novel and a book about Hackney.” “Good God! I can find 20 people to write picaresque novels about Hackney. I want someone who writes dull-as-ditchwater technical material.”

At the end of Cohen’s first month, Adrian Seligman, who ran the operation, told Lyne they were going to have a big party. “What are we celebrating?” “Henry’s departure. He’s a marvellous writer, but it takes him weeks to polish a paragraph.”

After this setback, news of Cohen came by way of an accountant, Leslie Periton. Periton was a partner in the firm of AT Shenhalls, who represented Terence Rattigan, Benjamin Britten and Leslie Howard. Lehmann persuaded them to take on the promising young winner of the Somerset Maugham award. Periton and Lyne had lunch together, once a year. “Henry was exactly the type Periton wanted,” Lyne said, “a man who didn’t have any interest in making money. Periton probably got him the job at MGM to keep him afloat. Nobody knows if Henry ever wrote anything else under another name. My view is, at the times I ran into him, he was a declining person. He had problems with his inamorata.”

At one of these epic lunches, somewhere in the mid-60s, Periton said to Lyne: “It’s all up.” “What’s happened?” “Henry’s not so good. In fact, he’s dead.” Nobody knew the details, aorta, aneurism. Showing me his inscribed copy of Scamp, without the Minton dustwrapper, Lyne was visibly moved. “Accumulated memories do work their way to the surface. I have a notion Henry married his lady. They had a child. It could be a whole new chapter in Henry’s story.”

From time to time, in a half-hearted way, I tried to interest publishers in bringing Camberton back into print. I was an admirer of the series of London Books Classics being put out by John King and his partners. In considering Rain on the Pavements they made the usual attempts to find the person who held the copyright and they came up with a name: Claire Camberton. Could this be the child mentioned by Lyne? I was given Claire’s details and a meeting was arranged.

A woman with bright eyes, animate but tentative, arrived on my doorstep, dragging a large red case on wheels. She was, as she told me, no stranger to Hackney. She brought reams of documentation, photocopies of letters, snapshots, books: the fruits of 20 years’ research. She was astonished to meet another Camberton enthusiast and we were instantly exchanging snippets of information, trying to fit the jigsaw together. Claire was indeed the daughter of Henry Cohen, but not the child of the late marriage. Her story was unexpected and poignant.

“I was born in December 1954. My mother’s name was Lilian Joyce Brown. She was from Andover in Hampshire. She lived in London during the war, working as a silver-service waitress at the Savoy. She was three years younger than my father. She died 20 years ago at the age of 64. She was a bit reclusive towards the end of her life and fairly secretive too.”

Lilian Brown met Henry Cohen when she attended one of the evening classes he gave, in short-story writing, at the City Literary Institute in Covent Garden. Lilian, her daughter recalls, was a pretty woman who was frustrated by her lack of formal education. She had a sharp eye for antiques and secondhand books and she haunted street markets. Very soon an affair was under way: “Mum liked Jewish men; it was a bit rebellious at the time. My father pursued her and chatted her up. Mum told me, in her rather prim way, that he was very virile.”

They came to an arrangement: she would carry Cohen’s child and, after giving birth, hand her over. Cohen’s mistress of the moment, a Jewish woman, couldn’t have children. Claire’s mother moved to London, Thornton Street on the Stockwell-Brixton border, and she received an allowance of £26 a month from Cohen’s solicitors. She changed her name by deed poll to Camberton. Life in those ground-floor flats, as Claire remembers it, consisted of “plastic knives and forks and making do”. The Camberton pseudonym had a simple explanation. “My father made the name up by combining Camberwell and Brixton. He hated them both. He hated coming south of the river. He was very proud of the fact that he lived in Chelsea.”

Lilian decided to keep the baby. A terrible scene ensued, the last time the infant Claire saw her father. “It was all Hollywood then. Everything was a story, a romance. When mum decided to call herself Camberton, my father slid away. He ended the association.” The estranged couple met on Clapham Common in 1956. “My father produced a huge stack of legal papers and presented them to my mother. Isn’t that dramatic? I was in the pram. That was their final parting, the end of the relationship. There was no further point of contact.” It was like a replay of an image from Graham Greene’s Clapham Common novel of secrets and betrayal, The End of the Affair.

As Claire pointed out, the character Margaret in Scamp seems to be a guilty memory of her father’s relationship with Lilian Brown; even though Scamp was published before her parents met. “It’s a melodramatic plot line,” Claire said. “She’s three months pregnant and she kills herself. The whole theme is right there: a woman who is not of his class, not in his league, and having a child. That’s probably why he didn’t want my mother to read it.”

Scamp presents an anti-hero, Ginsberg, who courts failure, relishes obscurity, and has an eye for a waitress. “Ginsberg was very much aware of her desirable presence by his side; so delightful were her little moues and winks that he . . . felt like . . . whispering into her ear an invitation.” There was another woman in reserve. “Until Lolita became his mistress, Ginsberg was delighted with the novelty of this courtship. But afterwards there was nothing to sustain their relations except recrudescent desire . . . Ginsberg was also still ashamed of Lolita’s background, which, though it might supply colour for an adventure, an anecdote, made a long-term affair impossible. At the same time he was ashamed of being ashamed . . .”

Among Claire’s papers was a photocopy of “Truant Muse”, an article by June Rose published in the Jewish Chronicle in 1965, just before Camberton died. Rose wanted to discover why certain writers “whose names were once well known . . . sped into obscurity”. Cohen, she decided, was “the kind of individual who finds it pleasant to vegetate”. He retreated to a bungalow beside the sea. “London history is his special subject and he writes with erudition and clarity in small reviews.” The article is accompanied by a photograph: a balding, melancholy man. Like a cinema organist after the coming of sound. Here, without question, is the stalking figure drawn by Minton for the cover of Scamp. That image is taken from life.

And there is one more surprise: a “major work”, never published, Tango. The journal of a hitch-hiking odyssey around Britain, an English On the Road. “The writing is at times Orwellian,” Rose enthuses. Camberton laid out his plans in a letter to the Jewish Chronicle. “My intention is to make two journeys: one, partly on foot, through Europe . . . and the second to North America.” Tango was rejected by his publisher and has not resurfaced.

“Roland Camberton is essentially an isolated figure,” Rose concluded. “A man in a mackintosh, dignified, anonymous, alone. He is isolated from other writers, from the Jewish community . . . and his essential anonymity implies almost an element of choice.”

A firm of Wimbledon solicitors informed Claire’s mother that Cohen had changed his name a second time, shortly before his marriage. The new name was never to be revealed. The allowance would stop. The site of the grave would remain a secret.

I had been chasing the wrong story. Dying at the age of 44, Ronald Camberton left behind books that are worth searching out, as well as the lost manuscript of a journey on foot across Europe. At that point in my own life, I had scarcely begun; a bookseller in Uppingham was considering taking a punt on my first eccentric novel. I had lived in Hackney for 20 years without becoming part of its dream.

· Iain Sinclair’s Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire will be published by Hamish Hamilton in February next year.