Not one, but two titles for 2011’s book of the year award: Roy Wilkinson’s Do It For Your Mum and Mike Carter’s fantastic One Man & His Bike both managed to get unanimous love from the bailiffs and the bait boys at Caught by the River HQ. Special mentions also for: Sara Gran – City of the Dead (Faber), Jon Berry – Beneath The Black Water (History Press) and A Train To Catch (Medlar), Edward Hogan – The Hunger Trace (Simon & Schuster), Shaun Ryder – Twistin’ My Melon (Bantam), Teju Cole – Open City (Faber), Philip Connors – Fire Season: Field Notes From a Wilderness Lookout (Macmillan), Paul Cook – Lost In A Quiet World (Harper Fine Angling Books), Ian Sinclair – Ghost Milk (Hamish Hamilton), Dorian Lynskey – 33 Revolutions Per Minute (Faber), Robin Turner & Paul Moody – The Search for the Perfect Pub: Looking for the Moon Under Water (Orion).

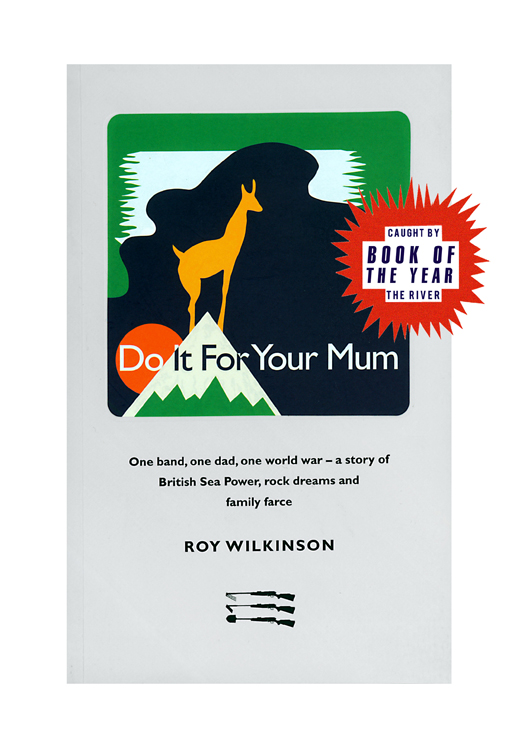

Do It For Your Mum. by Roy Wilkinson (Rough Trade Books)

The 21st century is underway. British Sea Power have been signed by Rough Trade Records and are working toward their debut album. Up in Cumbria, the band and their surrounding alternative-rock milieu are increasingly fascinating Ronald Wilkinson – the near-80-year-old father of BSP members Yan and Hamilton and also father of Roy Wilkinson, author of Do It For Your Mum.

As 2002 wound around the summer solstice, we were out on tour. We were out in the woods with two strangely alluring creatures. There was Jarvis Cocker and there was the European nightjar. Happily we would encounter auld Cocker on other occasions in the future. But concert itineraries would maybe never again take us so close to the nightjar – that enigmatic bird of the twilight hours, a creature also known as churn-owl, gabble ratch and goatsucker. In the fullness of time the now defunct magazine The Face would ask British Sea Power to select a ‘top ten’. Lemmy chose his ten favourite bass players: 1. John Entwistle, 2. Paul McCartney… 8. Corey Parks of Nashville Pussy. At British Sea Power we chose our ten favourite colloquial names of British birds. The nightjar only got to number eight. Imagine the other contenders.

1. Cuckoo – Welsh ambassador

2. Great crested grebe – arsefoot

3. Blackcap – nettle monger

4. Fulmar – flying milkbottle

5. Peregrine falcon – tiercel gentle

6. Snipe – galloping horseman of Lapland

7. Swift – devil squealer

8. Nightjar – goatsucker

9. Wren – two fingers

10. Redstart – arrogant cat of the east

This was the stuff – being given the leeway to lever a little avian wonder into pop press, alongside the club news and underwear by Roberto Cavalli. If we’d called it a day right there, future archaeologists might have found tiny traces of a mission accomplished, a kind of victory. Plus at least one made-up name to imperceptibly broaden the world of nature slang. But if pissing about and combining rock with non-rock was the mission, there was more work to be done. The summer of 2002 brought great opportunity on this front – supporting Pulp on a tour of Forestry Commission woodlands.

BSP had signed to Rough Trade in 2001. But it was in 2002 that we began to really grapple with that great entertainment staple – on-the-road-live-on-tour-in-concert. In 2002 the band played Glastonbury Festival and made their overseas debut, but the best of it was the sylvan safari with the man in the synthetic-fibre safari suit. The forest dates with Jarvis and Pulp would take us from the Scottish Highlands to the brecks and pines of East Anglian. If new rock contexts were sought, then these were good places to visit. Out in the woods there were no standard-issue rock-venue notices warning you not to try to sneak in booze, drugs and recording devices. Instead the trees were pinned with grave announcements. ‘NO FIRES. NO GAZEBOS.’

As we got to grips with touring, many things were as they’d always been. A fractional distillation of petroleum in the tank. Endlessly different towns with the endlessly similar nightshift sullenness of bouncers and venue staff. Who could blame them? At the rock coalface, things often slogged on deadeningly. Carling lager was on sale. The dressing rooms were coated in grime and lumpen graffiti These places sometimes suggested Victorian child chimney-sweeps. In both cases the workers were locked away from the sun – and surrounded by powders and residues injurious to health and vitality.

As basic as our touring regime could be, we were a long, long way from the worst of it. The historical iniquities were legend. As when Duke Ellington was forbidden to stay at the same hotels he’d played in, subject to the colour bars of 1930s America. Or when the pale, ghostly frame of Hank Williams was jammed into the back of a car on endless drives across the American interior. The prescription drugs and bootleg white lightning failed to block out the pain from his spina bifida. He was dead at twenty-nine, after one injection too many of morphine and vitamin B12. Even in 1960s Britain an apparently successful middle-class band like Pink Floyd could experience the kind of touring vicissitudes we would never have to face. As they reached the UK top ten with their ‘See Emily Play’ single, the gradually unravelling Syd Barrett and the rest of the band were relentlessly rolled out on package tours. There were engagements at the Gwent Constabulary Dance in Abergavenny. Pink Floyd took their place on a package tour that also featured Jimi Hendrix and Amen Corner. Sometimes Pink Floyd were given eight minutes on stage – this for a band whose composition ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ could quite happily fill twenty minutes. At one date they came off stage to be confronted with a stern promoter: ‘You were thirty seconds over. Do that again and you’re off the tour.’

With BSP signed to Rough Trade and the band now traversing the land, our father’s interest in the band began to accelerate. His indie-rock enthusiasms were growing more involved, ever more surprising. As we joined the Pulp tour in 2002, Dad was turning seventy-eight. Our first date with Pulp was a long drive from the band’s Sussex base – up near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. We broke the long journey north with a stopover in Cumbria. Some of the tour party, including myself and my two BSP brothers, stayed with our parents at the family home in Natland. It was lovely to see Mum and Dad and the old familiar fields of South Lakeland. But the surrounding greenery was overshadowed by Dad’s growing indie-rock monomania. As we arrived he pointed out a selection of vinyl albums and twelve-inch singles he’d been listening to. There was an album by The Associates, the great Dundee glam-romantics who sang of Belgian wharfs and ‘Breathless Beauxillous griffin’. There was also an album by the US rasta-punkers of Bad Brains and a record by Swans. The latter’s blasts of loud Nietzscheian post-punk grind included songs such as ‘Raping a Slave’ and ‘The Great Annihilator’.

As background research for our current tour, Dad had also dug out an ancient early Pulp EP from 1985, an artefact from the group’s long pre-success years. The tracks included ‘Little Girl (with Blue Eyes)’ and ‘Will to Power’. Dad was surely demonstrating will to power on British Sea Power’s behalf. As he ushered us inside from the tour van, Dad told us how he’d written a letter to U2 asking for support slots. ‘I got an address for their record company from Kendal library,’ he explained. ‘U2 are charlatans, everyone knows that. But it’ll be good exposure.’ As Dad buttered some teacakes, his conversation turned to Nick Cave.

In Natland, things seemed to proceed at immemorial pace. Delicious smells drifted in from the kitchen. The cows’ heavy udders swayed on the way in for milking. But some things had changed. The council had recently installed central heating at the family home. Who’d have thought it? But Dad’s new enthusiasms were even more remarkable. As we unpacked our toothbrushes he asked after the four Scott Walker solo albums, Scott to Scott 4. These CDs had sat in the house for years, but I’d recently taken them away south. ‘Oh, I see. I wanted to listen to those,’ Dad complained good-naturedly.

Dad wanted to talk about BSP all through dinner. Then, after he’d done the washing-up, he ushered me aside for the perfect post-prandial relaxation – systematic chronological analysis of a new BSP demo. He insisted we listen to the song on CD as he went through the two pages of notes he’d compiled: ‘The guitars should be louder here… The chorus should be repeated. Yes, repeated, definitely… Ah, I call this section “requiem for paradise”. Beautiful…’ His analysis progressed through a series of onomatopoeic waymarks: the ‘nig-nig-nig guitar bit’; ‘the boof-boof-boof drums’. Each point was accompanied by intense gestures. There was an impassioned choreography of pointed fingers. Then an expansive spreading of the arms. It was easily the equal of Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

Do It For Your Mum, can be bought from the Caught by the River shop, priced £13.50