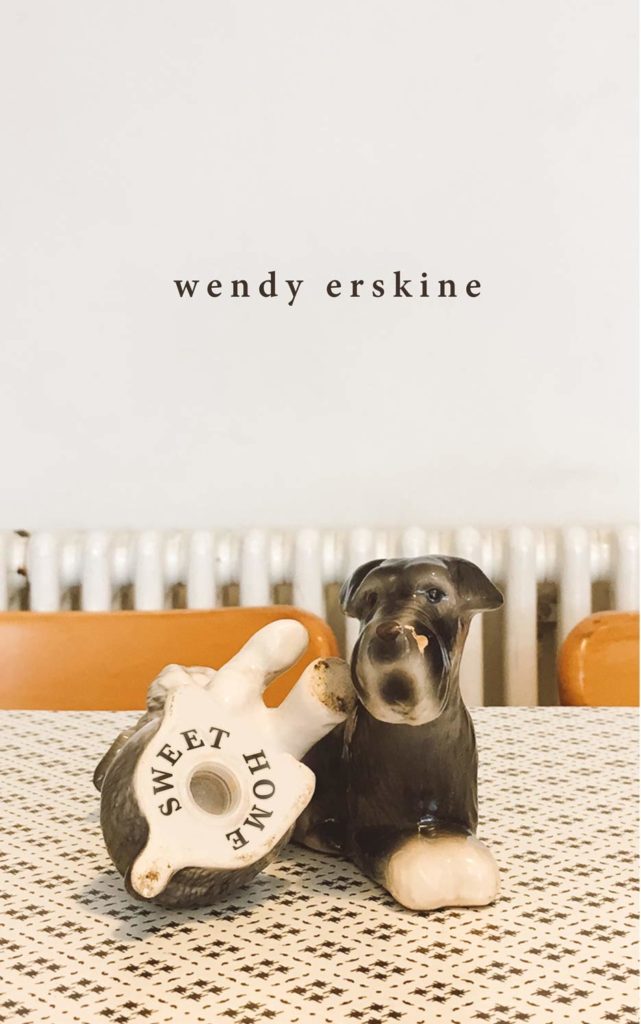

Wendy Erskine’s debut, Sweet Home – a collection of short stories set in contemporary Belfast – was originally published by Dublin’s Stinging Fly Press in 2018. Now, as it gets a Picador re-print (and, as we swing into July, it becomes our Book of the Month) Kerri ní Dochartaigh examines it in all its rawness, delicacy and beauty of place.

The first time I observed Wendy Erskine reading her work I felt like I’d wandered into a dark room in which something powerful, spine-tingling and utterly against all laws had just taken place. There was an energy pounding itself towards me off the low stage, not of a physical form – despite her definite and bewitching stage presence – but an energy that we’ve only really recently started to try to name.

I was sitting in The Playhouse Theatre in my hometown of Derry, an hour and a bit over the Glenshane Pass from East Belfast – the setting for most of the remarkable and singularly masterful stories in Sweet Home, first published by Dublin’s Stinging Fly Press last year, with Picador acquiring international rights the very same year. The Picador hardback has an eye-catching cover with wee chipped ceramic dogs and the tops of orange chairs; a scene which for me well sums up the odd and somewhat disarming portrayal of domestic life inside.

That particular energy present on the stage brought Erskine’s story up off the page, out of the theatre, and right out into the blood-red heart of the city, even. I pictured Erskine’s story doing a round of Derry’s 400 year old Walls – observing the hoods throwing their cans down into the Bog, the Creggan wains now old enough for ‘going steady’ sauntering around holding hands in their matching trackies; the tourists unpacking all their mixed-up views of that brick, graffitied, man-made boundary (now that they were actually standing on what had once stood only on their TV screen. )

The gig featured readings from Female Lines, an anthology of 13 women writers, poets and playwrights from Northern Ireland that volunteered short readings, to reflect on 68 – a hugely important year for the island of Ireland – in their work. Despite their differences in background, what all the readers shared that night was a desire to insert women’s voices into the narrative. Indeed, the story Erskine shared brought the female voice to the stage, as many of the stories in Sweet Home do, but there is so much more going on in these stories; these stories are, in fact – levelers.

In a Belfast Telegraph article in September last year, Wendy Erskine shared that she is: ‘interested in people on the side-lines, those who aren’t the centre of attention, the lives quietly lived.’ This collection takes the everyday – the more than mundane – and makes it rattle, a little, just a wee bit; just enough for music to be found in the half-light of its startling told truths.

Erskine’s writing is that rare breed by which I am constantly bowled over. Her attention to detail and heart-wrenching, hysterical telling of it left me howling – all the types – for almost the entire 48 hour period in which I devoured this dazzling collection. I found such resonance in the material here; the things, happenings and people in these stories speak the language of the world that I have grown up in. There has been much talk recently – and rightly so – of the importance of seeing your own experiences in the literature that is around you. As Jessica Andrews says in the acknowledgements of her debut Saltwater, writing is often about ‘making space in places where there is not enough’.

This year alone I have been brimming with joy as Sinéad Gleeson, Jan Carson, Wendy Erskine and a handful of other outstanding Irish writers – from both sides of that invisible border – have taken the rawness and complexities of life on this island and placed it on the page in the most exquisite ways; palatable and glistening. In this collection, Erskine is very much making space in places that, until very recently, didn’t have enough for so very many of us.

Last month, in an interview for the Irish Independent, Jan Carson spoke a little of her journey towards writing her own lived experience:

‘As a young writer, I didn’t see my culture represented in the books I read…For years I wrote stories set elsewhere because I didn’t believe anyone would want to read about the places and people familiar to me. Lack of representation inspires lack of representation. It’s a vicious cycle, which has undoubtedly had an impact on diversity within the North’s literary canon…Many local writers no longer claim allegiance to either of the two traditional sides…The notion of what it means to write from, and of, the North of Ireland has never been more complex or intriguing.’

Like Carson, Erskine gives us the characters that are in fact the stuff of real life, albeit in a somewhat surreal light. We find characters that I, for one, have met in my own hometown, or have heard others slag off or fall a wee bit in love with. Young folk trying to save enough to make a real future for themselves – in call centres they can’t stand – alongside slimy paramilitary blokes still not willing to let the ‘polis’ take care of matters for local businesses, and, of course: ‘It’s all about community. Communities don’t run themselves.’

But Erskine doesn’t just leave it there. The figures in her stories run deep enough that they linger under the surface – parts of them come back to us a few hours later, forcing us to look at them, and their actions – in a softer light. Kyle is not given to us as just a bullying lout. Kyle remembering ‘the sound of cracking bone and the way a lip swells’ – as he thinks back on the violence that his own (far from sweet) home was subjected to by his father – was the single most emphatic moment for me in the collection.

There are Fathers in this collection. They bully and neglect their children; they disapprove of the names those children have been called. They do not give the slightest time of day to their own, lonely Mam, all because they have ‘a son who…doesn’t even speak the same language’; instead idolising (without justification) their own dead father before them. They are absent, the Fathers, and that emptiness breeds darkness. They wear suits to police Stations. They are not really fathers but are – almost – in the place of them; with lines so blurred as to be achingly uncomfortable. They are Preachers that embarrass young girls terrified by their sexuality; winning battles with being heard because they are a father that owns an amp. There is an unlikely individual – a blow in – who relocates from England to his own Fatherland – a ‘had been’ Father. There is a church café boss who fathers his sinning employees. There is, of course, also, that Father up above; I absolutely adore the way religion is treated in Sweet Home.

We’ve got the changing face of the North of Ireland (and the distaste for some about the fact that some of these faces are more or less covered up.) In ‘Inakeen’, we are given a devastatingly tender glimpse of another aspect at play; the story long being played out in the North of Ireland – the way that lots of people simply leave. Jean – my favourite character in the collection – has lost a husband and, more or less, a son. She is affected more, though, by the loss of her grandson and his mother who move to Canada. And perhaps the thing that causes Jean most suffering of all is when she fears she has lost the family of women living next to her, despite not even knowing their names.

Sorrow, loneliness, suffering and the ever-pulling tide of what could have been run through these stories like a golden thread. It is right there, in the very beginning. ‘You could feel them sometimes, people’s hopes, even though all you wanted to do was just get on with your job.’

People hide away, often living in isolation; moving about ‘in the dead of night.’

Strangulation, self harm, abuse, terrorism, prison, death, sex, gender, identity, obsessive behaviours, old age; why – OH WHY– would you ask? But the thing is Wendy Erskine does ask.

Her attention to detail is astounding – from the way the brains of people work once they have stood knee deep in the bog-land of violence to the smell of a load of washing when a teenager first senses her sexuality (involving the only Kerri I have ever found in a story.)

Word choice and sentence structure is mind-blowing in Erskine’s work- from how nail varnishes fall off a counter, to their owner ruling the line for Tuesday in her diary to the bottom so she can afford to replace her smashed window.

Intimacy is here too – how we relate and bring joy or pain to the other – what people think about; who, why and how they love.

There is more than a full rainbow in these stories; there is just so much colour dripping out of them: nail varnish bottles, dresses, paint. In ‘Locksmiths’, the story that secured Erskine’s place at The Stinging Fly’s workshop where it all began, a yellow bloom is painted over following the smoker’s death. There is matching orange hair, a room without bars that is ‘white, white and white. With a side helping of white’– its occupant with white, scarred skin to match – where once there was an orange rug. Most poignant of all is the ‘blue holdall’ in the front room at the end of this moving telling of domestic life as many people do not know it.

The second time I was in the same room as Wendy Erskine, we were in an audience that was basking in the unimaginable splendour of Hannah Peel and Will Burns performing a live set of their album Chalk Hill Blue in Belfast’s Black Box. I was stood in the queue on my own waiting for my pal. When I turned around, Wendy Erskine was there. I knew – straight away – that I simply had to speak to her. To tell her – face-to-face – outside of those odd shared places like Instagram and Twitter, how grateful I am that she wrote her stories down. I tell her that I love her writing, and that my partner really loved her music choices on ‘Mystery Train’, the space he discovered her in. I tell her how buzzin’ I am for her that she will be reading her work at a Caught by the River event (hashtag “BUZZIN-LIKE-MY-BALLYMAC-COUSIN” as they say down my way.)

You see, it means a lot to me – a wile, wile lot – that Erskine’s voice is one that I will be hearing; and hearing it in places I so much want to hear it in.

These are indeed, “Changed times”on this wee island – and changing, still – and aren’t we all so very glad of it; and of talent such as this that makes the place sing.

*

The Picador edition of Sweet Home is out now and available to buy here in the Caught by the River shop, priced £12.99. Wendy reads from the book, and discusses it with David Keenan, at our upcoming FICTION event in Hebden Bridge on 6 July. Tickets for this event are available to buy or claim for free, as with the Calderside Disco which follows it. More info here.

Kerri ní Dochartaigh lives in northwest Ireland. She writes about nature, literature and place for publications which include Oh Comely magazine, New Welsh Review and The London Magazine. You can follow her on Instagram here, Twitter here, and she publishes new writing on her blog here.