Melissa Mouchemore crosses from Penzance to the Scilly Isles by ferry – and shares the dramatic series of events which led to her dad sending out a Mayday signal in 1967.

One evening in 1981, Paul McCartney, Carl Perkins and George Martin were on board Mike Batt’s yacht, The Braemar. He had stopped off with his family in Montserrat on his circumnavigation of the world. Paul and George were on the island to record with Stevie Wonder. Batt bumped into them and invited them to dinner – The Braemar had a uniformed crew to serve the food and a ‘music room’ complete with piano. Unsurprisingly the evening soon became a singalong including ‘Let It Be’, ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and ‘Ilkley Moor Ba’ Tat’. The drinks flowed and the crew were invited to join in, one deckhand singing his own composition – pretty brave considering the company. It was called ‘Froggy’ and included a croaking chorus, leading Batt to wonder if this was where the idea for the ‘Frog Chorus’ began. What a night!

George Martin was particularly interested in the navigation equipment on board and asked about the history of the Braemar – Batt thought he might have been a ‘nautical type’ during the war and he was right; Martin joined the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy in 1943 when he was 17. I don’t know what Batt knew of the Braemar’s history but I could have told him a thing or two. In my family we knew another very different episode in the life of the yacht; one that led to my father sending out a Mayday.

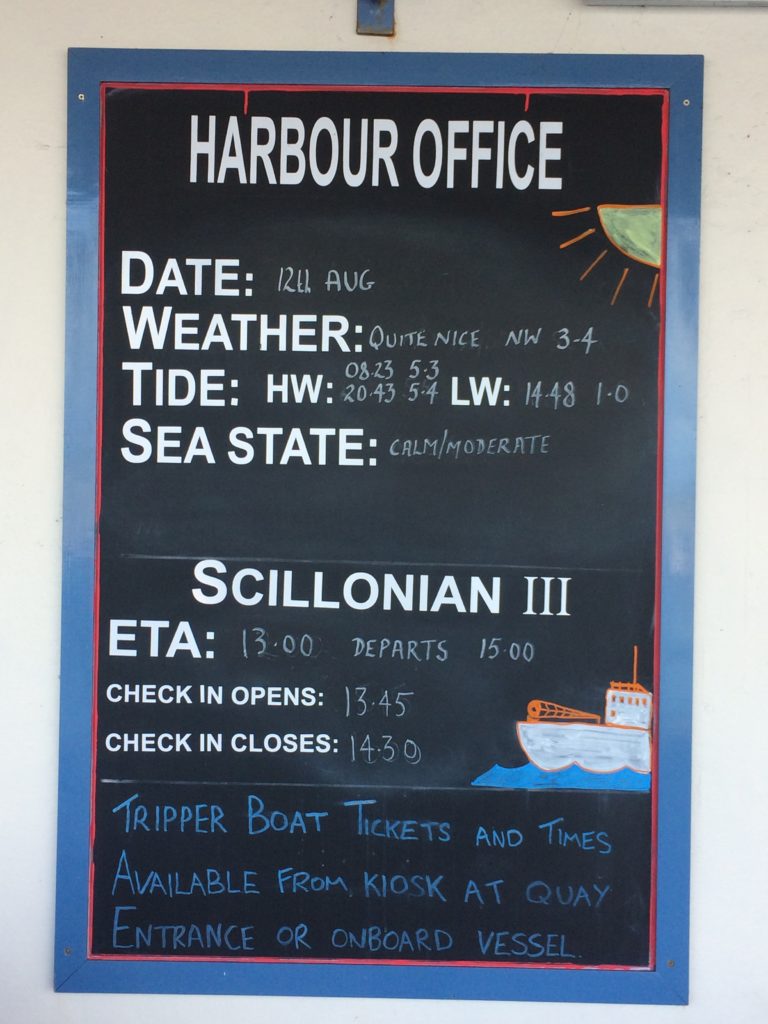

I think about that now on a wet quayside in Penzance. I am about to board the Scillonian III, the ferry that will take me to the Scilly Isles for the first time.

Ah The Sickonian! a colleague said gleefully. You’ll want to fly back – we did! The notorious Scillonian – so many tales of holidaymakers, green as they arrive in St.Mary’s pleading to be taken to the airport to book their return.

It is smaller than I expected, the design a standard child’s drawing of a boat; two masts front and back, funnel in the middle, two rows of windows beneath the deck. A boat for a bath. I look towards the harbour entrance through sheets of rain – we are going beyond Land’s End where the English Channel meets the Atlantic and where that Mayday was sent out.

‘When I was on the Braemar’ was a phrase of my father’s I always knew growing up. At some point I worked out that the Braemar was a boat.

In my late teens my parents took their first flight to the Scilly Isles and I realized this was something to do with Dad being ‘on the Braemar’. He had been determined to buy a drink for a man called Matt Lethbridge. Matt couldn’t be persuaded but his brother Harry took up the offer. I have a photo of them on St. Mary’s quay, Dad in his anorak and Harry in skipper’s cap and canvas trousers stained with a mixture of diesel, oil and fish.

And then as a student the full story of Dad being ‘on the Braemar’ was revealed to me via the tiny black and white TV in my basement flat. As an ITV sound man Dad had often done the ‘pick-ups’ for This Is Your Life – the opening shots at the start of the programme where the presenter Eamonn Andrews surprised whichever personality with the symbolic red book and announced; ‘Tonight name of personality this is your life.’ But on this occasion Dad wasn’t making the programme, he was a guest. This Is Your Life was doing Matt Lethbridge who, I discovered, was the much-decorated coxswain of the Scilly Isles lifeboat.

Recently, having a clear-out, I found the programme’s script; extraordinary tales of rescues against the odds; Torre Canyon, Fastnet, the Penzance – Scilly helicopter crash…saved Scilly Islanders talking of their faith in Matt:

“But I shouted to the others at the top of my voice – Matt will be coming! Matt will come to save us!”

And grateful sea captains:

“And you kept coming back alongside until every one of us was safely aboard your lifeboat …”

Then the moment I had been waiting for;

EAMONN:

Matt, in May 1967 it’s the homecoming of round-the-world yachtsman Sir Francis Chichester and ITN send a reporter and technical team to take a look at conditions to prepare for their live coverage. Their chartered yacht, the Braemar is 30 miles off the Scilly Isles in thrashing seas…water starts to pour into the engine room. This message – actually recorded on the spot at the time- goes out.

/TAPE: MAYDAY/

My father’s voice – all his years as an ardent sea cadet, junior radio ham and finally, at just 17, a wartime Merchant Navy radio officer, his training kicking in – Mayday, Mayday. A steady voice in a turbulent sea and a sinking boat.

The Braemar had set out from Shoreham, Sussex. Along with the This Is Your Life script I have a collection of photos, cuttings and diary entries. The Brighton Evening Argus was one of many papers to feature articles on the technical challenges for the ITN team.

OFF TO ‘SHOOT’ SIR FRANCIS

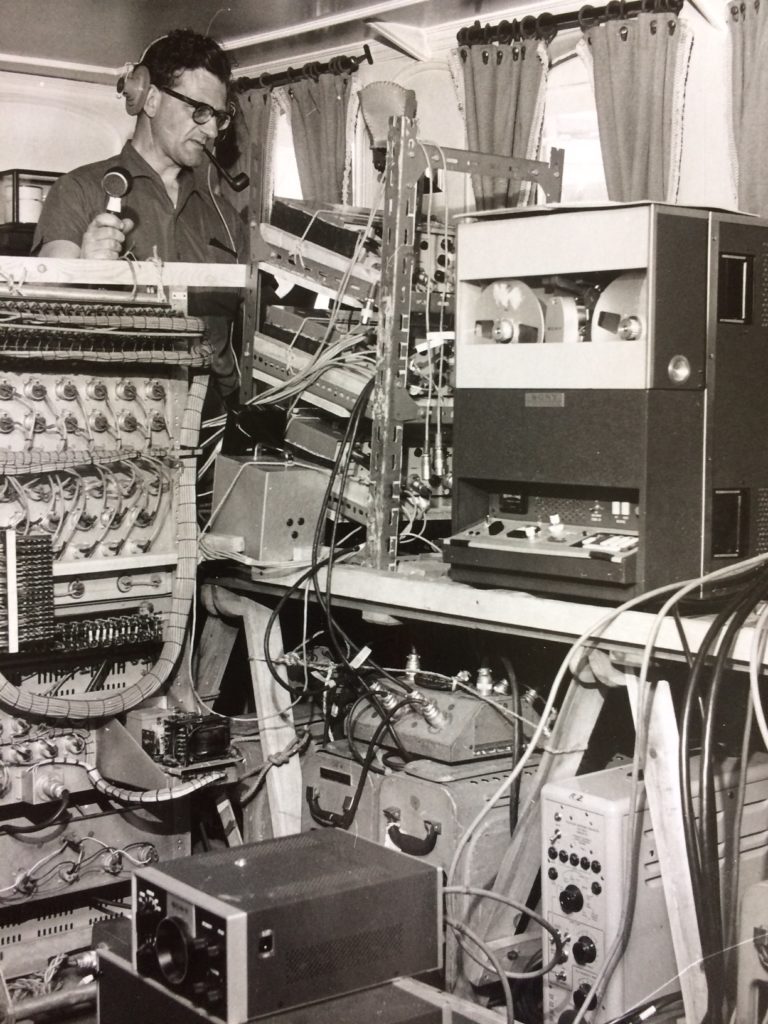

The Braemar sails on Saturday with orders to intercept Sir Francis Chichester in the Bay of Biscay…(it) is packed with the latest electronic equipment and the aft saloon has been converted into a sea-going studio.

My father is quoted;

“You can take it from me –we shall find the Gypsy Moth. There are enormous resources at our disposal and we have every kind of aid.“

And he meant enormous. A black and white photo accompanying the article shows this ‘sea-going’ studio – reel to reel tape decks the size of washing machines, a mass of snaking wires, dials, knobs and the sort of switches that made a satisfying ‘clunk’. A B-movie mad scientist lab of sound. Behind the stacked equipment, only the head and shoulders of his 6ft frame showing, stands my father with his two most favoured ‘props’ – headphones and pipe. In life he was not especially confident but when it came to sound equipment and radio waves he embodied the company motto of Associated Rediffusion Television – Never Baffled.

And he was not alone. The rest of the TV crew had what today would be called a ‘can do’ attitude.

A young technician, 23 year old microphone operator Richard Spriggs, kept a diary at the outset of the voyage:

“We fitted up yet another transmitter for the plane to home on to. Disaster, nothing to wind loading coil. Quick visit to forward lavatory provided suitable cardboard tube. Problem – what to do with 800 ft of perforated paper?”

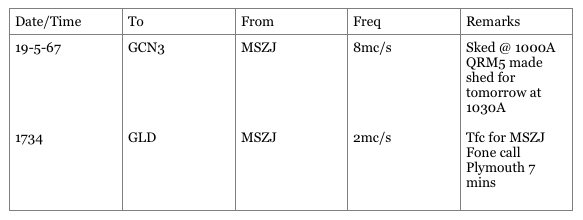

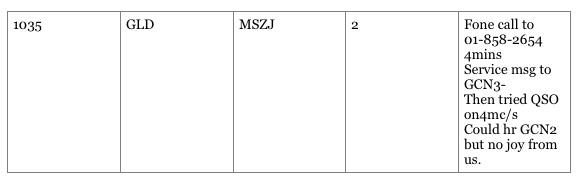

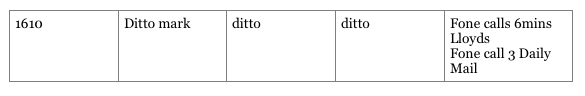

Meanwhile my father set up his CONTROL ROOM RADIO LOG; the title promises a weighty document but is in fact just 3 blotched notebook pages, held together with his trademark yellow insulating tape. It starts off neatly as an exact record of all radio traffic using the sort of abbreviations he expected his family to understand when he left us notes:

Several days later The Sun reported:

The ITV men sailed on Saturday to check if it was possible to relay pictures from mid-ocean by bouncing them from an overhead aircraft to the GPO receiving station at Goonhilly. An ITN official said last night: ‘The test was successful. The pictures were received clearly.“

Of course there was the small matter of the sea – although my father had earned his sea legs from Rio to Calcutta, sea-faring experience was not essential amongst the TV team – there was a ship’s captain (also the boat owner) and 2 crew members to actually sail the thing.

Richard Spriggs’ diary captures the wonder of a first time voyager;

Clear when I got up but sea fog fell. Ringing bell every minute. Sailing back sea fog lifts. Sea blue-green, fabulous.

And the challenges:

Quite exciting to see the breakers coming over the bows, felt very tired and rather strange…Very rough in the night, ship goes round and round. Everything banging, waves outside the porthole.

Back on the Scillonian as it thrums past the smudgy coastline of Cornwall, I am waiting for strangeness to strike. In the packed cafeteria I sip tea standing up. Many passengers it would appear either have sturdy sea legs or are oblivious to all notoriety and warnings, tucking into sausage rolls, pasties and choc chip muffins.

Through the window the boat gently banks like a plane – sky horizon, sky horizon. The occasional stall or jolt but nothing to make me or the pasty-eaters stagger to the loungers down below.

It seems such a waste of a journey to stay inside so I put up my hood and go out on deck. I want to taste the salt and peer down at the wash of the waves; the Alka Seltzer fizz of the wake, the frothy white arc the bow makes as it ploughs along. “The boat’s got a bone between its teeth” Dad would say.

After a few days on board the Braemar, Richard Spriggs was picking up the odd nautical term, clearly fascinated by the adventure;

We have swung at anchor…Went with Richard Lindley in tender to Falmouth …Suggested design for lifejacket.

If only the pesky sea would stop moving. After a week of technical trials as they inched closer to Land’s End and the Atlantic, they were about to set sail again from Falmouth to Penzance;

Gale warning for Plymouth. Force 8 that’s us. Put ITV banners up. Very windy. Barograph rising again means winds.

With a challenge ahead;

The BBC boys expect Sir Francis on June 2nd or 3rd. I had a look at the charts and cannot see how we can hope to find him.

It is hard, in these times of drones and a sky full of space junk constantly telling us where we are, to comprehend both the technical challenge and race to be first amongst the TV teams – ITV had only been around to compete with the BBC for just over a decade. And the level of national fuss about Chichester’s admittedly impressive round the world feat; once he had sailed up the Thames to Greenwich, The Queen was going to dub Sir Francis with the sword given by Queen Elizabeth 1 to Sir Francis Drake. What a theatrical coup, two pairs of namesakes – a symmetrical gift. Surely with this sort of symbolism Britain’s power in the world couldn’t have ebbed away?

And so on the team pressed on May 20th into a force 8 gale; the Spriggs diary tellingly stops here and the story continues through the account my father wrote for a staff magazine, and of course the CONTROL ROOM RADIO LOG which by 21st was being written in blunt pencil, less neat, a couple of crossings out, legibility slightly compromised but still sticking to original tabular form:

Up and down, round and round – what else can you expect in a force 8 gale. But it was in the early hours of May 22nd that things started to go properly wrong, as my father recounts;

Around 5 am the news spread that the Braemar was making water in the engine room.

The press getting hold of the story started to use terms like ‘flooding’ and ‘giant seas’, but men who were Never Baffled just said ‘making water’, put on their lifejackets and stood ready to help. My father was at his post, radio control log at hand and Richard Spriggs relayed messages to the bridge. The operator at Land’s End joked:

We’ll make sailors of you yet.

At 6.48am, the Scilly Isles lifeboat was launched.

I have always been aware of lifeboat rescues – I watched Blue Peter as a child after all. But I had not given enough thought to what a rescue might actually entail. I am grateful for the cuttings, Dad’s account and log…and of course, Eamonn:

EAMONN:

When you launch the lifeboat Matt you’d no idea it was the beginning of a non-stop rescue battle that was to take a staggering total of 21 hours and save the lives of 19 people aboard…

21 hours, the first 7 or so spent just trying to attach a towing line. At first it was hoped that a nearby ship The Trader would be able to tow them to safety. But in the terrible conditions the ship couldn’t even find them on the radar until the Never Baffled team and another toilet roll somehow gave The Trader a radio bearing. Even then, firing rockets carrying the line kept missing the mark. The lifeboat, sometimes disappearing from view in the wave troughs, managed to come alongside the yacht and ferry a line across. But still the line kept snapping. When the lifeboat took over the tow all were hopeful but again the line snapped, severed by the Braemar’s broken fairlead. Never Baffled, not even in Force 8, one member of the TV team suggested using the anchor chain as the link over the bows. The line finally held.

On the Scillonian the churning waves are yielding strands of ice pack blue, flint and jet. Rain crackles on my hood and I dodge mini waterfalls splattering from the roof as the ferry pitches. But I know these conditions are relatively benign. The coast line is looking less friendly though – any gentle wooded slopes have now given way to a bleaker, harder-nosed promontory of rock stacks. A white and grey building, radio mast on top is just visible through the gloom. Land’s End. The Scillonian’s radar spins as if in salute. I clock the life rafts on board. What would I be doing during a sea rescue? Holding on tight, that’s what.

The Never Baffled lot were doing what they knew best – filming – with Richard Lindley reporting and Richard Spriggs struggling through relentless sea-sickness to help out with microphone cables.

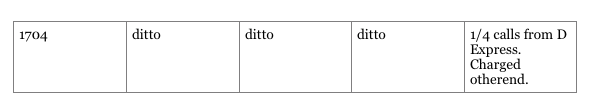

Once the tow was fixed the radio log could be resumed – in black pen, blue pen, black again. The occasional ditto mark appears.

A big arrow points to scrawlier writing added above the table, possibly to explain the gap in recording;

A lot of Mayday B4 this.

A tug coming to help had to turn back at The Lizard – too rough. So now it was all up to the lifeboat to take them back to Newlyn; it clawed through the seas at 3 knots all afternoon, dragging the 170-tonne yacht which was refusing to point in the right direction, preferring beam on to the high seas. Both engines had long since conked out as water rose and it now had a pronounced list. As the evening’s darkness drew in it was judged time to transfer everybody to the lifeboat.

The last entries in the log are around 90 mins before they abandoned ship including one at 1704 – I can just about read the entry:

Get off the phone Daily Express! They are sinking!

Matt Lethbridge was notoriously a man of few public words. However there is one detailed quote from him about the rescue in the West Evening Herald;

“Taking people off was the worst part. We took them off starboard when the yacht was listing. The deck of the yacht was heaving on to the lifeboat and when her top rail rolled level with our top rail we dragged some of them on board. Others jumped.“

I cannot imagine I would have jumped, having to judge the leap from 1 pitching vessel to the other – dragging would have been my only option.

In his account my father included a description of what it was like on the lifeboat;

While the Braemar had wallowed through the sea, the lifeboat was like a cork on the raging waves. It bobbed and jumped almost as wildly as a bucking bronco. It was like being on one of those whirling fairground rides that goes up and down as it twists.

He added grimly;

“Many were violently ill”.

And there was yet one more problem. Three people had refused to leave the Braemar – the captain along with his two crew; how tight-lipped must the lifeboat crew have been at this point?

So Matt Lethbridge had no choice but to keep towing. By the time they reached Newlyn Harbour at 2.15 am on May 23rd, they had been huddled in the bucking bronco for 7 very long hours.

On board the Scillonian the rain has miraculously stopped, patches of blue sky have appeared. Up on deck phones are being activated, there is laughter and the islands are in view now, a mirage coming nearer. It hasn’t been one of those trips. We have been spared.

The Exeter Express and Echo reported the arrival of the knackered Braemar – all who had gone through the ordeal were reported to be in good health ‘except for one man, probably a victim of extreme seasickness, who had to be carried off.’

This was Richard Spriggs at the end of his maiden voyage. As he was whisked away to hospital my father remembers him saying, ‘goodnight everybody’.

There was a crowd on the quay, floodlights, cameras flashing. But no recovery time. The team immediately began hauling the equipment off, the tape of the rescue attempts sent ready for the next ITN bulletin.

And Sir Francis was still on his way. By the next day a Dutch coaster had been booked and there was a hectic rush to rig her – reel-to-reel washing machines off one vessel and on to another.

As for Matt Lethbridge, after a few comments to the local press, the Never Baffled men marvelled as he and his crew set off long before dawn back to the Scillies, several more hours of tumbling sea away. It must have stayed in Dad’s mind, seeing them go, to travel to the Scillies and buy that man a drink, or try to…

Although of course there was one other time to say thank you;

EAMONN:

That globe-trotting reporter Richard Lindley can’t be with us tonight…

TYMPS

LS FOR ENTRANCE

/DOORS OPEN/

…But here are that television crew…

FANFARE

ALL ENTER, GREET AND SIT

One member of the crew was noticeably missing. For the day after the rescue news came from West Cornwall hospital that young Richard Spriggs who had seemed to be recovering, had suddenly died. Heart failure. So much promise, lively intelligence and determination not to be baffled. Yet none of us know if we have strong enough hearts to take on the sea.

The Scillonian is coming in gradually by the low water route through St Mary’s Sound between the islands of St. Agnes and St. Mary’s. A lighthouse perches on metal latticework. We pass outcrops; headlands strewn with strangely-shaped granite, as if giant children had been given a large batch of salt dough to mould and had left their creations to harden in the sun and wind. Lots of it hurled into the sea too. I check the map. Each abandoned piece has a name – Big Jolly, Little Jolly, Tooth Rock. And in between are lighter grey names with dates attached – Royal Oak 1665, Kitty O’Flanagan 1838…the more I look the more light grey names appear in the water – Unnamed Venetian Merchantman 1780, U681 1944, Quicksilver, Hope, Charming Molly, Earl of Arran – no matter how noble, charming or hopeful your name, or if you have no name or just a number, the sea and its toothy rocks can have you all.

And one other name rises to my attention – just off the southernmost tip of St. Agnes – Scillonian stranded 1951. What conditions forced it so dangerously off course? I am very grateful that we are sticking to the dotted line, already rounding St. Mary’s Garrison.

Just 3 days after the Braemar rescue on Friday 26th May 1967, both the ITN and BBC vessels managed to make contact with Sir Francis. The ITN plane made the link but the BBC helicopter had not been able to take off in the storm. And so the first live pictures of Sir Francis Chichester’s homecoming came from ITN. A cause for celebration? The team must have had very mixed feelings.

Although the management was pleased. All members of the TV crew received letters of commendation and 21 guineas ‘in appreciation of your exemplary devotion to duty on the occasion of the Chichester outside broadcasts’.

I don’t know for sure what happened to all those 21 guineas, but the Richard Spriggs Memorial Fund was promptly set up by the team, providing grants for promising young TV technicians to study further. My father and other crew members were on the board of trustees.

There was an RNLI silver medal for Matt Lethbridge and 2 bronze for his crew, but also some controversy in the aftermath of the rescue. The St. Mary’s lifeboat put in a salvage claim for the Braemar and this was frowned upon at RNLI headquarters in London. A spokesman sniffily described the behavior as ‘almost the wrecker instinct’.

The response from St. Mary’s was terse;

‘This station very seldom puts in a claim. 19 men were rescued from the Braemar and the lifeboat took 13 hours to tow her into Newlyn. She was carrying a lot of television equipment…’

I wonder if Mike Batt knew this episode in the Braemar’s history and how the Scilly Isles lifeboat made that heady night in 1981, possibly even the Frog Chorus, possible? George Martin would have been interested – he was clearly a man who was Never Baffled.

As we round Rat Island here is Hugh Town, our destination. Tight knit, taciturn rows of granite cottages line the harbour, cedar trees stand protectively at the town’s edges – at first I feel we might be trespassing. But facing us across a placid, light refracted pool of tethered dinghies and fishing boats, perched on a granite outcrop is a slipway down to the water, 2 red solid boathouse doors at the top, ready at any time to open and make an offering of a boat.

It is time to make my own offering.