On the eve of the second anniversary of Scott Walker’s death, Mark Brend recalls the thrill of chasing a coveted copy of ‘Scott 4’.

Though it seems impossible now even to imagine it, once, there was a lost estate of music, apparently inaccessible forever. Before streaming and before the CD reissue goldrush that preceded streaming, there was a time when almost the entire history of recorded music was not just a few clicks away. Some of us remember this.

Records were released, and if they sold well they would probably be kept on catalogue. You might find them racked in record shops. If not, you would be able to order them at the counter. When they didn’t sell well – or sometimes when they did – they would be deleted. (Pet Sounds, for example, was out of print for a few years in the early 70s). This meant that no new stock would be pressed up, and once any remaining new stock sold through the only way you could get a copy was if you got lucky in a second-hand shop. It was like this until at least the end of the 1980s. By which time there had been several decades full of millions of records – rockabilly, soul, psychedelia, disco, prog, punk, folk, garage rock, reggae and any other genre you can think of. Almost all of which you couldn’t readily find. And about which you might, if you were lucky, unearth scraps of information that would stimulate a profound, tantalising nostalgia for a past that you knew had existed, quite recently.

But this past was a foreign country that you could not visit. Though from time to time, if you loitered at the checkpoint long enough, you might hear a distant voice calling from over the border. Or receive a smuggled message of what it was like, back over there.

If, like me, you were a teenager in the late 70s, poring over the weekly music press and the few music references books then available, you would have been be aware – for example – that in the 1960s, only a decade past, there had been a band called the Electric Prunes. An American garage band that, in contrast to most American garage bands, had actually managed a couple of international hit singles. If you were particularly studious in pursuit of the arcane you would have discovered that they had a career of sorts, releasing five albums. Now, you can listen to that band’s entire recorded output for free, plus watch multiple clips of US TV appearances for good measure. Then, in the late 1970s, almost all of this music could not be located. Most likely you knew just one song, ‘I Had Too Much To Dream (Last Night)’, which featured on the Nuggets compilation of US garage and psychedelic bands. This had been released first in 1972, was soon deleted, and then reissued in 1976. You would have rejoiced when Radar Records reissued ‘Dream’ as a 7-inch single in 1979, which gave you access to another song on the B-side (‘Luvin’ – not that good, really). But that was it. Unless you had the cash to spend in a collectors’ shop. Maybe – just maybe – you’d chance upon the B-road route to hearing more Electric Prunes music. If – and it was a big if – you had a friend, or more likely a friend with an older friend, with whom you could trade a second or third generation cassette. All hiss and wow and flutter. But it never satisfied. If anything it provoked to an ever more intense pitch a longing for the real thing.

This pining for a past just out of reach first took hold of me when I read a three-volume NME history of rock. Volume 2 has an entry titled ‘punk rock’ but the book just pre-dated punk in the Sex Pistols sense. It starts off:

‘Punk rock was a style that flourished during the years 1964 to 1967, reflecting America’s grassroots response to the British invasion…’

It then goes on to list bands like the Seeds and the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. The Electric Prunes aren’t mentioned, but warrant an entry of their own, describing ‘Dream’ as a “minor punk rock classic.” I read those words in 1977, when UK punk was in full swing. For a short while I laboured under the misapprehension that in 60s America there were lots of bands that sounded like the Adverts. I loved those bands before I ever heard them. Just the names had a sort of incantatory power. Question Mark and the Mysterians, Mouse and The Traps, the Shadows of Knight. I was captivated and spent hours in anticipatory adoration, speculating and wondering. What sort of lives did these people lead? Were they still alive? If so, what did they do now? Yet almost all of that music was out of my reach. In a sense, its absence was its delight. In time I came to love those bands again, in a different way, when Radar and other labels started to reissue some of those records. At which point I realised the music was nothing like the Adverts.

What seems unfathomable now is that, to a teenager in the late 70s, 60s punk/psych/garage rock seemed impossibly, exotically distant. Yet when I first got interested the records were only 10 or 12 years old, and most of the band members were not yet 30. As I write this, in 2021, do teenagers think of music from 2009 – 2011 in the same way? Judging from the reactions of my own teenage children, I don’t think so. All culture is now present.

But that’s how it was. You knew there had been much music made that you would love if only you could get to hear it. But you couldn’t. It was locked up in history. An extinct language. And this provoked something akin to – and maybe even an expression of – the longing for God. The mystery. The faith in things unseen.

Which brings us to Scott Walker. I had first become aware of him as a member of the Walker Brothers. Not through their classic 60s hits, but their later cover of ‘No Regrets’. I first started to listen to pop music intentionally in 1975. That year the Walker Brothers reformed, having split up in 1967. In the intervening years Scott had launched a solo career that burned bright and faded fast, leaving him serving time in MoR purgatory, repackaged on budget label Contour. The Walkers’ first release on reforming, ‘No Regrets’, was the only UK hit of this second coming. They mimed to it on Top of The Pops, and for a couple of months it was on Radio 1 several times a day, every day. Which meant I heard a lot of it.

In those days I had no taste. Or maybe I had taste in the purest, most innocent sense. What I didn’t have was any judgement of what might be critically acceptable by the standards of the day, or credible. I simply liked a song or I didn’t like a song. And I really liked ‘No Regrets’. It stayed with me. When I wrote my first book, American Troubadours, in 2000, it included a chapter on Tom Rush, the composer of ‘No Regrets’. I knew by then that the Walker Brothers’ cover was a pretty faithful copy of the second version of the song Rush himself had recorded. I asked him how he felt when their version, not his, was an international hit single. He seemed pretty relaxed about it, saying words to the effect of: “I did alright out of it. And imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”

In 1975 I was oblivious that for a few years in the late 1960s Scott had embarked on the oddest of solo careers. Simultaneously exemplar of cool and supper club TV variety crooner. Art Scott and Showbiz Scott. As far as I was concerned he was one of three brothers (real brothers, for all I knew), permed medallion men, all open-necked denim and suntans. A few years later Julian Cope repackaged Art Scott for the post punk audience. By that time I knew about the Walker Brothers’ 60s hits, but still little about what happened in the years after those hits dried up and the 1975 re-emergence.

In part through Cope’s flag-waving, I eventually discovered that after the Walker Brothers split in 1967 Scott embarked on a solo career. His first two albums, Scott (now often called Scott 1) and Scott 2 (1968), embrace the contradictions in his career, mixing Brel covers, originals and mature pop. They sold well and weren’t too hard to find years later. By Scott 3 (released March 1969) there were intimations of change. It seemed Art Scott was prevailing. Mildly dissonant strings on ‘It’s Raining Today’ anticipate later experimental work, while the orchestrations are a few bricks short of the wall of sound approach that characterised both the Walker Brothers and the first two solo albums. There were more Scott originals, too, with just three covers, all Brel songs. The album was top 10 in the UK but didn’t hang around in the chart as long as 1 and 2, a hint that Walker’s audience was diminishing.

Even so, it still seemed like a buoyant career. Showbiz Scott stepped forward again. At 9.55pm on Tuesday 11 March 1969, Walker opened the first of six 25-minute episodes of his own BBC1 TV series, following two pilots a year earlier. He sang some hits and standards, and introduced guest artistes drawn from the lighter end of the entertainment spectrum: Dudley Moore, Kiki Dee, Jackie Trent, Tony Hatch. No footage remains apart from snippets of the pilots. Audio bootlegs of the series give the impression that Walker seemed not as uncomfortable as you might expect.

Without breaking stride Showbiz Scott then released a non-album single that was to be his last solo hit, ‘Lights of Cincinnati’ (June) and the album Scott Sings Songs From His TV Series (July). This comprised re-recordings of some of the covers he’d sung in the TV series. Art Scott responded by producing two British jazz albums, Ray Warleigh’s First Album and Fallout by Terry Smith.

A notably fertile year if he’d stopped right there. Personally, I Iike all of the music Walker produced in this period, but it seems like he was a divided soul. Amidst all this antithetical noise surfaced whispers of discontent. Walker told the Melody Maker “I want to be alone”, then cancelled a week’s residency at the Golden Garter Theatre in Manchester. Where, that same year, Bob Monkhouse, Tessie O’Shea, Freddie and the Dreamers and Jimmy Edwards had all topped the bill. Henceforth, he announced, he would work under his birth name.

So it was Noel Scott Engel, not Scott Walker, who released Scott 4 in November 1969. Ten excellent songs, all originals, sympathetically arranged, immaculately produced by John Franz, and of course sung to perfection. Opening in widescreen with ‘Seventh Seal’, based on Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film, much of the rest of the album settles into something more intimate, more fragile. ‘Boy Child’, which closes side one, is lyrically impressionistic, a touchstone Walker composition. With no drums and an ascending melody picked out on what is probably a cimbalom, it hints at his later abstract style. On side two ‘The Old Man’s Back Again (Dedicated to the Neo-Stalinist Regime)’ motors along on a loping bassline at odds with the dour, furrowed impression of the polytechnic activist’s subtitle. The album closes with the second of two country-influenced ballads, ‘Rhymes of Goodbye’. Everyone now hails Scott 4 as a classic. Yet when it was released in November 1969 it failed.

Why? Maybe an album that opens with a song about a knight playing chess with Death was doomed from the start. The salient point is that it didn’t sell, didn’t chart and was soon deleted. Which meant that by – say – the end of 1970 you couldn’t buy it anywhere.

In 1981 the Cope-compiled Fire Escape in the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker introduced late 60s Art Scott, expressed most completely on Scott 4, to the era’s NME readers. This compilation, too, was soon deleted. It included three songs from Scott 4: ‘Seventh Seal’, ‘Angels of Ashes’ and ‘Boychild’. They seemed like miracles. Resurrections. Not just distant, ghostly voices from the other side, which maybe you heard, maybe you didn’t. But clear, unmistakable statements. The past came to life.

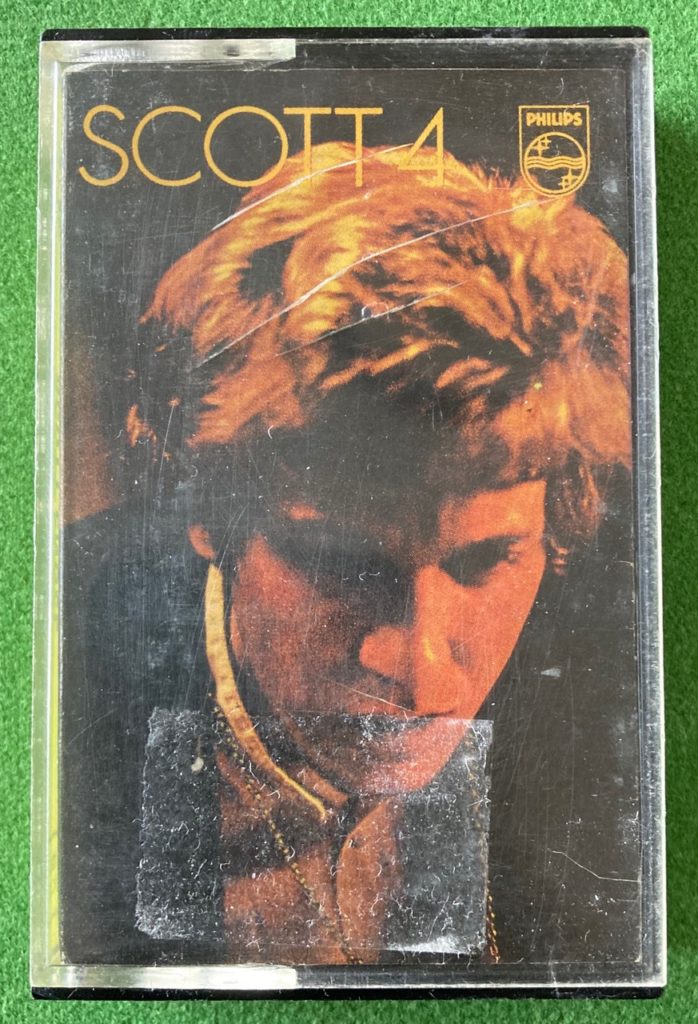

By then, though, Scott 4 itself was all but unobtainable. I didn’t even see a copy, let alone hear it, until I began working in the deletions department of the Record and Tape Exchange in Notting Hill Gate, in the mid-80s. Occasionally it turned up, but I couldn’t afford it, even with staff discount. There was a sort of etiquette, a mild version of a criminal code of honour, which said you could take home the records for yourself, blind eyes turned, as long as they weren’t worth too much. But by then a mint version of Scott 4 was worth a bit, and I never felt able to liberate it. Perhaps others had fewer qualms. I don’t know. Anyway, my chance came when a haul of pre-recorded Scott Walker cassettes came in, including Scott 4. Cassettes – even original pre-recorded ones – then had little value to the serious collector. So I bagged the lot, with an almost clear conscience. It was 1986.

Pre-recorded cassettes first appeared in the mid-1960s but didn’t really take off until the late 70s. And cassettes made in the 60s and early 70s were poor quality, too, so tended not to last. Subsequent research proved that an original pre-recorded cassette of Scott 4 is scarcer even than an original vinyl pressing. How many still exist? Who now could say? I’d guess we’re into double figures, but maybe only just. The haul also included a cassette of 4’s follow up ‘Til The Band Comes In, this time credited to Scott Walker, not Noel Scott Engel. Original issues of this, too, are rare, though it isn’t so sought after. I sold it on eBay in 2020 for £30. I considered auctioning the Scott 4 cassette, too, but didn’t in the end.

Among my friends the Scott 4 cassette took on mystical, talismanic significance, something like a holy relic. My band, the Palace of Light, was recording its sole album that summer. Decades later, Stewart Lee – one of the very few to discover our album when it was released in 1987 – was writing liner notes for a thirtieth anniversary reissue. Geoff, the singer and co-songwriter in the band, said to him:

“I am transported back to a day in…86 when we finally tracked down a copy of Scott 4 and sat in reverential silence before the altar of my old Mission 700 speakers.”

Matt, the bassist, has a faint recollection of me bringing the album home from work, though in his memory it was a vinyl copy, not a cassette.

Nick, our friend, thinks he can remember the same event, or maybe another one. In his mind a small group of people, not including me, sat in the kitchen of the band’s flat and listened to a copy of my cassette:

“I can see the Scott 4 cassette in my mind’s eye, bluish cassette shell, someone’s – Matt’s or Geoff’s – handwriting. Matt’s I think…I’m sure that first listen for us was a copy. Although memory can be a traitor.”

Often, memory is a traitor. But this much I know. The Scott 4 cassette came from the Record and Tape Exchange. It is real. I have it still. Nick remembers it. He remembers, too, finding a vinyl copy for £6 in Brighton, probably just weeks or months after I got my cassette. Most likely, memories of both items and subsequent listening events became conflated in our collective memory.

By 1986 we all knew Scott Walker and the Walker Brothers. They were an influence. Indeed, when our album was released reviews compared Geoff’s voice to Scott’s. With hindsight this was lazy writing, though we weren’t complaining. Then and even now, it’s a trope of music journalism to compare a full-voiced male baritone with Scott Walker.

I have a memory of an associated event from this time that may not ever have happened. Yet maybe it did. The recollection is cloudy. We all – Geoff, Matt, Nick and me – lived in the Highgate/Archway area of North London. Geoff and Matt were in the band flat, from which I had moved out a year before. We had heard that Scott Walker lived in North London at the time. Somebody had told us that they knew someone who had played bass for Scott and had been to his flat. We found an N S Engel in the telephone directory, in Highbury. We phoned the number. That’s as far as I go. Nick thinks he might remember one of us holding the phone while the others crowded around. He says:

“What really sticks in my mind is the darts thing. Cries of ‘one hundred and eighty!’ And ‘this morning I played darts with death…’”

This is a reference to a 1984 interview in the NME, when Scott, asked what he was doing, replied that he spent a lot of time in pubs watching people play darts. All of this is uncertain. I’ll never know if we called whoever that N S Engel in Highbury was. Maybe we just said we would. But I hope we did.

The first car I owned with a cassette player was a 1980 metallic gold Fiat X19. It had a removable targa hard top that you could store under the bonnet. I bought it around 1990. I had a cassette box that I kept on the floor of the passenger footwell, with room for about 20 cassettes. These included Love’s Forever Changes, a bootleg of the first, abandoned version of Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks and Scott 4. All liberated from the Record and Tape Exchange, which I had left some years before. I lived in London but drove down to Devon half a dozen times a year. Often I might leave London at 11pm, after a band rehearsal, arriving in the early hours. Driving over Salisbury plain at 1am with the roof off, listening to Scott 4 or Arthur Lee at full blast as I passed an illuminated Stonehenge.

The cassette player in that car all but did for the Scott 4 cassette. The music became muffled and indistinct, as if it were slipping back into the past, but I didn’t really mind. Scott 4 was reissued on CD in 1992, under the name Scott Walker, not Noel Scott Engel. I bought a copy and put the cassette away in a box. In about 2018 I saw a new vinyl pressing for sale in Sainsbury’s, alongside Led Zeppelin and ABBA and AC/DC. Now a canonical work.

What was lost is now found. Most of it, anyway. But near-comprehensive availability brings its own deprivation. There is nothing left to discover. I listen to pretty much anything I like, at a few seconds’ notice. But I wonder if I preferred it before. I miss the quest. Almost everyone I know of about my age understands this tension. We have everything. Except that expectant hope of discovery, that foreshadowing of glory. Which, we are surprised to find, we treasure above all else. Funny thing is, we know we’ve been played. The market sidles up and whispers that the more choice we have, the fuller life will be. We know it isn’t true, and yet, unfathomably, we fall for it every time. And the Devil looks on with a nod of approval. Or – as Scott would have it – “and Death hid within his cloak and smiled.”

*

Mark Brend is a writer of fiction. He also writes about and makes music. Follow him on Twitter / visit his website.