Lucia Dove delves into Ken Worpole’s ‘No Matter How Many Skies Have Fallen’, which tells of the pacifists who took possession of Frating Hall Farm, Essex, in 1943.

‘The land has been humanized, through and through: and we in our own tissued consciousness bear the results of this humanization.‘ – D.H. Lawrence, Sea and Sardinia

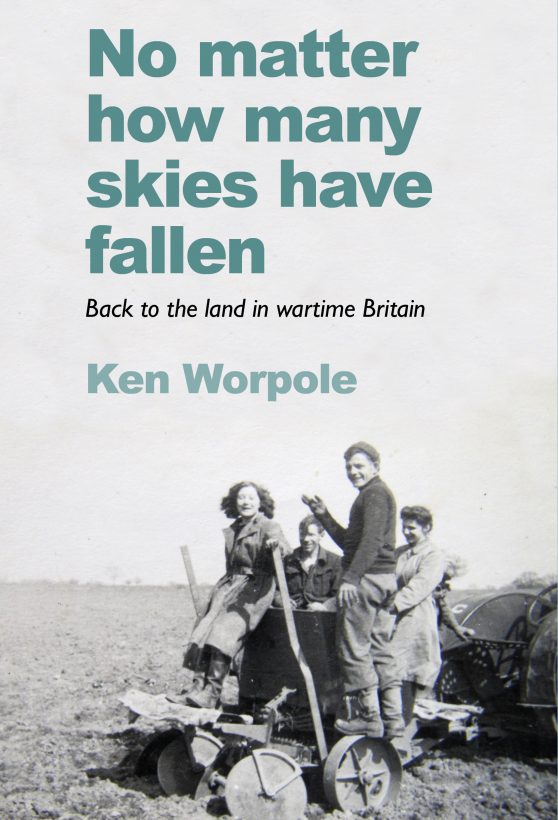

In his carefully researched and moving new book, No Matter How Many Skies Have Fallen: Back to the Land in Wartime Britain, Ken Worpole chronicles a history of radical pacifists who set out to establish working communities in twentieth-century Britain; thinkers and do-ers who moved beyond the need for a sense of community and achieved a new way of living at Langham and eventually Frating Hall in rural North Essex. The book is exceptional in its ability to inform about the political, social and literary landscapes of the time, as well as the geological landscape in East Anglia, but also how these often complex and conflicting histories are presented so compassionately. This is an honest story of the vicissitudes of struggles and joys of imagining, forming and dismantling communities.

We find the title of the book in its epigraph, a quote from D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover: ‘We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.’ A time where people fight to live, skies are on fire, war burgeons and societal aggressions isolate one another from their neighbours. It is, of course, a mirror to our times: a pandemic that initially stopped the project in its tracks; extreme weather caused by environmental breakdown; polarising media and political instability. ‘Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically’, writes Lawrence in the opening sentence of the epigraph. At times personal (admitting that he, too, was escaping to Frating by working on this project), Worpole’s telling of the stories of collective perseverance in times of fear and disunity feel as astute to this reader as the words of D.H. Lawrence might have felt to John Middleton Murry, the founding editor of the literary and cultural journal The Adelphi and The Adelphi Centre at Langham. It was from Langham that the Frating Hall community developed, to explore new ways of living, to find ‘new little habitats, new little hopes’.

The project originated with an essay on alternative communities published in the fantastic Radical Essex (Focal Point Gallery, 2018). The introduction serves to orientate the reader on the key religious and political ideas, the notable (often forgotten) thinkers and, finally, the conceptual understandings of the farm. The connection between labour, rural living, nature and the human condition forms the very real and sometimes tragic underpinnings of the story. Following the introduction, the book is divided into seven parts where Worpole weaves biographies, philosophies, first-hand accounts and charming images, guiding the reader through a bygone terrain that at times feels so familiar.

The trajectory of establishing these communities was difficult and nonlinear. The results were not always prosperous, financially, socially or emotionally. What interested me, in particular, was the disparity between the lived experiences of men and women at Frating Hall, a subject I could have read more on. Worpole shows through testimonies that these considerable differences, ‘ranging from the traumatic to the idyllic, form an important part of the story’, but does not go further than acknowledging ‘whether the wider world offers anything more amenable to the differing needs and interests of women and men remains open to question.’ Worpole finds out that their clear policy on childcare was that it was not a collective responsibility, whereas the success of the endeavour as a whole was considered as such. It is an incongruity that reminds me of a description of Middleton Murry given by his daughter Katherine Murry, detailed at the start of the book. She writes that ‘the tragedy of her father’s life’ lay in part with his ‘idealisation of his first wife Katherine Mansfield’. Worpole recognises this sense of inadequacy in Murry’s own words, ‘I knew I was her (Mansfield’s) inferior in many ways, but I could have accepted them all save one. She had an immediate contact with life which was completely denied to me.’ It could be read that Middleton Murry’s ideals were partly constructed on gendered discontent, making it worthwhile, perhaps, to use a feminist lens to understand further the experiences of the women in the Frating Hall community.

Throughout, Worpole graciously allows the reader to make their own connections to current society, enabling immersion into the presented history. He does an excellent job in the final chapter where he takes necessary stock of the future of farming in Britain in the context of Brexit, the pandemic and environmental restoration. When I started reading this book, I didn’t imagine that I would be adding books on farming and smallholding onto my reading list, but as Worpole convincingly shows, ‘Food issues can bring farming and wider social and environmental concerns together, particularly in a time of crisis. […] Unwrap farming and you unwrap almost everything to do with human society and the natural world.’

At the end of the book, following a helpful Notes section and Bibliography, is the Appendix, titled ‘Prophets of the new world’. The title is taken from a proposed Workers’ Educational Association course by a Frating member who sought to highlight the writers and thinkers who informed his religious and political beliefs, many of which were his companions at the farm. Borrowing Raymond Williams’s understanding of community, as cited in the book, that community is an ongoing process and that people are not in the community but in community, one has the impression after finishing this intelligent and compelling book that Worpole has himself contributed to the fascinating Frating Hall Farm community. It is a great achievement.

*

Published by Little Toller, ‘No Matter How Many Skies Have Fallen’ is out now and available here.

Lucia Dove is a writer from Southend-on-Sea, Essex, living in the Netherlands. Her latest book ‘VLOED‘ (Dunlin Press, 2021) explores the shared cultural memory and landscape between Essex and the Netherlands in relation to the North Sea Flood of 1953. Follow her on Twitter @LuciaDove.