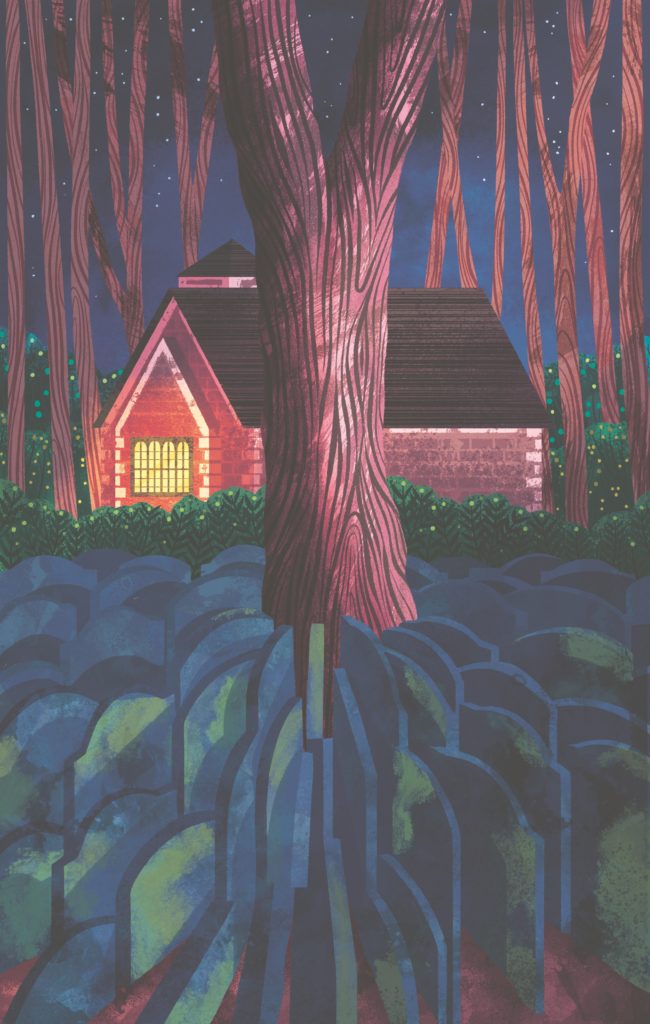

In celebration of National Tree Week, an extract from Mark Hooper’s ‘Great British Tree Biography’, published by Pavilion. With illustration by Amy Grimes.

Ash, St Pancras, London

Nestled in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church in London is a curiosity: amongst the tombs to the great and the good of 18th and 19th century London (Sir John Soane, Mary Wollstonecraft – mother of Mary Shelley – and Baroness Burdett Coutts), is a solitary ash tree, around which are laid hundreds of gravestones, set perpendicular to the tree and extended outwards in rings, many of them consumed by the roots and foliage.

The name of ‘The Hardy Tree’ relates not to the relative resilience of the ash tree and its roots, but to the assumed author of its design. This peculiar monument dates back to the 1860s, when plans for the new Midland Grand Railway in King’s Cross ran across an area of the church’s cemetery. The work of designing the new line was assigned to the architect Arthur Blomfield (1829-1899), a proponent of the Gothic Revival style and famed for his designs for Covent Garden. As for the unpleasant job of overseeing the disinterment and reburial of many of the remains in the churchyard – Blomfield delegated that to his young assistant, a promising young architecture graduate from Dorset… by the name of Thomas Hardy.

Before his fame as one of the pre-eminent writers in Victorian Britain, Hardy (1840-1928) had first trained under a local architect in Dorchester. In 1862, at the age of 21, he moved to the capital, enrolling at King’s College London. As Mark Ford notes in his biographical work Thomas Hardy: Half a Londoner, Hardy made something of a name for himself, winning several prizes including a silver medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for his essay on ‘The Application of Coloured Bricks and Terra Cotta to Modern Architecture’ and a first prize from the Architectural Association for his designs for a country mansion.

It’s not certain how directly Hardy was responsible for laying the tombstones around the tree that bears his name, or if it was the artistic eye of one of his underlings who came up with the striking pattern. What we can be sure of is that, in 1865, Hardy was placed in charge of the excavation and reburial work by Blomfield, who he was assisting at the time. As such, he would undoubtedly have been aware of the work, and most likely instructed it to be carried out. What we can also be sure of is that he noted the gruesomeness of the task in his diaries and, by 1867, had returned to Dorset, apparently after being laid low by some form of nervous exhaustion.

Having first resumed work as an architect with his first employer in Dorchester, Hardy finally turned to a life in literature. His first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, was finished in 1867, the same year he returned to the West Country, but failed to find a publisher. Eventually, however, with the publication of Far From the Madding Crowd in 1874, Hardy was able to give up architecture, going on to become one of the most celebrated English authors in history. But not before leaving us with an unusual and macabre monument in the capital, with a backstory he would surely have appreciated…

*

Extracted from ‘The Great British Tree Biography: 50 legendary trees and the tales behind them’, written by Mark Hooper, illustrated by Amy Grimes, and published by Pavilion Books. Order a copy here (£15.79).