In an extract from ‘Welsh Plural: Essays on the Future of Wales’, folk musician Cerys Hafana reflects on collaborating and conflicting with Welsh history.

I am a Welsh folk musician, and to be a folk musician means to be constantly in collaboration and conflict with your history, or, as it’s more commonly known, “the tradition”. Musicians everywhere face choices as to whether to embrace, subvert or reject the tradition, but they will always be in a relationship with it. As a Welsh folk musician, the tradition within which I exist is defined by melodies, songs and instruments being passed down through the generations, unchanging. The story I am told usually focuses on the things that have stayed the same, the things that will always and forever make Welsh folk music Welsh.

But I believe the story of Welsh folk music could be told the opposite way: as a story of change, of new influences and ideas being brought in by people from other places, and a story of new struggles and challenges that will inevitably enact changes over the centuries. My definition of folk music: music that can, and will, be changed.

I have been playing the harp since I was eight. I started learning on the Celtic harp, before moving on to the triple harp, which has three rather than one row of strings, removing the need for levers or pedals to play chromatic notes. It originated in Italy as a baroque instrument, before arriving in London in the 17th century and being adopted by Welsh Londoners, soon becoming known as the Welsh harp. I’m lucky enough to be one of a tiny group of young people in Wales, and the world, who play this instrument today.

My first harp teacher’s house is a museum that also happens to be a home. It is exactly where you want to go to receive a thorough education in the history of Welsh folk music. You are surrounded by artefacts, manuscripts and instruments that are kept warm and loved, and which in other less careful hands may have found themselves gathering dust. My first harp teacher is a gatherer, a protector, a collector. She takes this job seriously. It is her lifeblood, her passion, but the responsibility weighs heavily on her shoulders.

She can often be found shaking her head and wringing her hands, aghast at the young people today who show no interest in their history or their music. Most of those who have taken on the role of protecting and preserving the tradition have an overwhelmingly pessimistic outlook on the future of Welsh folk music: these young people just don’t get it. They don’t care. They have no respect for history and tradition, no understanding of where they come from, and are changing Welsh folk music beyond recognition.

One of my formative experiences in folk music was attending an annual week-long course for young people at an outdoor education centre in north Wales. Before I arrived the first time, harp in tow, I was very much under the impression that I was the only young Welsh folk musician left in Wales. So what I found came as a bit of a rude awakening. There were about 50 other teenagers filling every corner of the centre with jigs and reels, singing folk songs in improvised four-part harmony until 3am. I spent most of my first visit hiding on the top bunk in my room, but over the years I began to feel more and more at home in this noisy, frenetic community of passionate young musicians.

This other tradition has a very different approach. Tunes are there to be used and abused. The musical points of reference come from far and wide, with jazz perhaps the most obvious external influence. I am now a member of the Youth Folk Ensemble of Wales, a continuation of the course, and though the majority of melodies and songs we use are Welsh, we have arrangements inspired by eastern European turbo folk and Daft Punk.

For a while, at these events, I felt as though I’d found “my people”. It was a breath of fresh air to me, as a young queer person with no friends at school, to be surrounded by such open-minded, enthusiastic and welcoming people. And then one night, while a group of us were sitting around playing games, the clock struck midnight and someone gleefully declared: “Right! It’s past midnight, which means we can now be as homophobic and racist as we like!” and proceeded to play a game involving guessing who in the room was most likely to be gay.

One key event in the Welsh folk calendar is the Mari Lwyd – a traditionally south-Walian celebration of the new year which, in short, involves a pub crawl with a horse’s skull on a stick. But the village of Dinas Mawddwy in Snowdonia in north Wales plays host to a Mari Lwyd that, despite being relatively recently established, pays its respects to much more traditional aspects of Welsh folk culture, perhaps most notably folk dancing, which takes place on the street, led by a group of dancers in authentic Welsh costumes. Everyone, regardless of age, nationality and language will come out, wait for the accordions and fiddles to start up, and be organised into pairs by the more seasoned dancers.

It is, however, incredibly important that these pairs are all man and woman. This is often checked a few times before starting a dance, to make sure everyone is following this sacred rule. And every time we change partner, I get asked the same question: “Are you a man or a woman?!” I try to answer with whichever I think I’m supposed to be in the dance, to minimise confusion. This may be a reinvented tradition, and it may involve a horse’s head on a stick and a man in drag, but heteronormativity and the gender binary are apparently two traditions that must be protected and respected at all costs.

I have a theory that the triple harp is seen by many as a symbol of Wales, its plight mirroring that of Wales and the Welsh language in the last century. Many influential players today came to the instrument as adults with a passion for Welsh history, and saw learning it as the ultimate manifestation of their interests. It is viewed as a kind of historical artefact, hailing from a better time when everyone in Wales spoke Welsh (and was born in Wales), when every young person was passionate about their native culture, and when rich landowners made their servants work in national dress in the name of preserving the tradition.

But when people imply that things were better for Wales back then, I can’t help but suspect that what that really means is that things were better for the Wales of rich white men. It’s an erasure of all the things that have changed for the better. And it’s an erasure of all the kinds of people who weren’t around, or weren’t able to participate then, but who have so much to offer now. Where do we draw the line between preserving tradition and excluding people who aren’t considered “traditional”?

*

08

Cerys Hafana is a triple harpist, pianist and composer from mid-Wales.

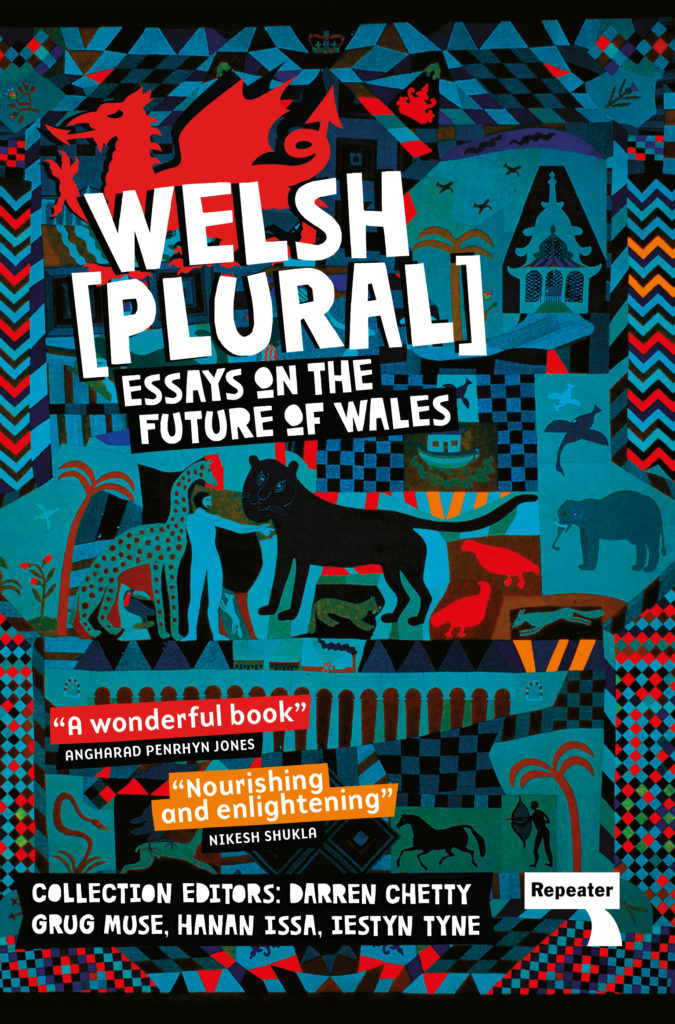

This is an edited extract from Welsh (Plural): Essay on the Future of Wales, edited by Darren Chetty, Grug Muse, Hanan Issa, and Iestyn Tyne, and published by Repeater.

As well as performing her music, Cerys joins Darren Chetty, Greg Muse and Andy Welch to read from and discuss ‘Welsh Plural’ at this weekend’s Camp Good Life. More information here.