Every year, we give over all of December (and usually most of January) to a series called ‘Shadows and Reflections’, in which our contributors share highs, lows and oddments from the past 12 months. Today it’s the turn of Jon Woolcott.

One day in early September, just after we moved to Dorset, my partner Helen and I took a colander and went blackberrying. We could have collected plenty of the ripe fruit from the hedgerows within fifty yards of our new home, but instead we walked a three-mile loop from our village to the next across the flat fields. It was, of course, an exploration, an unspoken beating of new bounds.

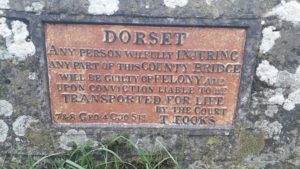

A narrow stone bridge crossed a brook. Screwed to its parapet Helen pointed out an old iron sign which read:

DORSET

ANY PERSON WILFULLY INJURING

ANY PART OF THIS COUNTY BRIDGE

WILL BE GUILTY OF FELONY AND

UPON CONVICTION LIABLE TO BE

TRANSPORTED FOR LIFE

BY THE COURT

T FOOKS

A few words were cast slightly larger, for emphasis: INJURING, COUNTY BRIDGE, FELONY, TRANSPORTED FOR LIFE. The largest word was DORSET.

*

I spent this year putting together my book Real Dorset. I spent day after day reading, taking notes, walking, cycling, travelling the county. I wanted to get under Dorset’s skin, and beyond its reputation: overshadowed by Hardy’s tragedies but these days often thought of as a county for holidays, a sense of a long and settled bucolic past. The iron sign, one of several identical notices screwed to bridges across the county, was a clue, an indication of something more troubling. I found them at Blandford Forum, where I flattened myself against the bridge’s parapet to avoid being swept into a lorry’s undertow, at Dorchester, in a lane near the village of Evershot. As far as I know, only Dorset has these notices. I read a whole book on the county’s bridges but found no reason why the authorities were keen to use the threat of transportation to protect them, except as a symbol of a cruel age, when membership of a Trades Union could also result in transportation, as at Tolpuddle.

As I travelled I learned rebellion and riot were stitched deeply into the fields, meadows, villages and towns, across the centuries. Dorset was continually wracked by uprisings. At the start of the nineteenth century, when the transportation notices were installed, Dorset’s Blackmore Vale, where I live, was notoriously poverty stricken. The enclosure acts, which effectively privatised the countryside and deprived the poor of land for grazing and firewood, affected rural communities everywhere, but Dorset’s agricultural wages were already the lowest in England (an unenviable record, held jointly with Norfolk). It was no surprise, then, that the 1830 Swing Riots spread quickly in Dorset. But this wasn’t a mindless uprising against the inevitable march of technology: these were considered actions, not taken lightly. The rioters often wore their best clothes to signify the importance of their mission, sometimes weaved laurel leaves into their clothing too, to signify peace or, even republicanism.

For the protesters a sense of place mattered. When landowners enclosed the Commons they imposed on the landscape new hedges and fences, symbols of a new poverty and infringements of ancient rights and customs. One winter morning I walked around the now quiet town of Stalbridge, finding a level piece of land where a grand country house once stood. The townspeople objected strongly to the house’s demolition by the absentee landowner because its destruction had disrupted a centuries old landscape. Its absence was felt keenly even by those who would never have set foot inside it. The land was fundamental to local folklore: it held the stories. Hedgerows at Mappowder were thought to be haunted by the spirits of gypsies who had been turned off the land, while further west a sixteenth century Cunning Man derived his power from a landscape where he saw faeries and sprites.

Here was a rich and subversive history. A windy walk across Hambledon Hill, a huge ancient earthwork where the chalk drops to the clay, was also to walk across a lost battlefield, where Cromwell’s dragoons destroyed the Clubmen, a largely forgotten west country grouping who defied both sides in the civil war. Described by Frederick Treves in his magisterial but occasionally comically snobbish 1906 book Highways and Byways in Dorset as ‘red-faced yokels’ and ‘muddle-headed’ in fact the Clubmen trod a careful line, attempting to shorten a war that claimed the lives of 100,000 people through careful, if doomed, negotiation.

At Lyme Regis I crunched over a pebble beach where the Duke of Monmouth landed and raised an army in 1685, planning to overthrow James II . Monmouth was unlucky (very unlucky — he was captured and summarily executed at the Tower of London), but he’d chosen Lyme with care, knowing he’d find a rebellious spirit. The town’s name had a royal suffix, but in the civil war had been staunchly Parliamentarian, holding out for months against the royalists. The deciding factor was the women of the town whose resistance was celebrated in radical London’s pamphlets of the time. Everywhere I found this resistance: at Easton in 1803, in what is now a peaceful park on always ornery Portland, a small, deadly battle broke out when a naval press gang clashed with inhabitants. At Christchurch smugglers trounced the Navy in a pitched battle and gave one of their own a decent burial having cut down the corpse which had been hung in chains as an example.

A sense of magic was a fundamental part of claiming the land. To help navigate the tangle of stories I gathered companions to walk with, people attuned to the mysterious: friends, musicians or poets, writers and historians, finding an obscure saint’s shrine, abandoned villages, burnt castles, smashed churches, a vanished mausoleum, holloways and barrows, a lost railway.

I had to keep my own fascination with decay in check. Dorset was no sarcophagus but was brimming with creativity and strange invention. I stumbled over a curious story involving the eccentric cult author Baron Corvo who may, or may not, have painted a mural on a Christchurch church wall in the 1890s, photographing his models leaping in mid-air to capture their poses. The sculptor Elizabeth Frink lived and worked on the steep slopes of Bulbarrow Hill, but I found the hill had also been the inspiration for a song by Half Man Half Biscuit. I walked a path under an impressively flamboyant disused railway bridge which led me to where Derek Jarman went to school, and inspired Jubilee, the closing scene of which is played out along the Dorset coast, recalled in his memoir Dancing Ledge, named after the cliffs where a schoolmaster dynamited a swimming pool from the rocks. In Bournemouth I stood in the carpark beneath which was buried the Winter Gardens, the legendary music venue which hosted performers including The Beatles, Buzzcocks (whose support was Joy Division), Richard Hell and the Voidoids, David Bowie, and its final act, Ken Dodd.

As a teenager I hated Thomas Hardy, awkward for someone writing a book about Dorset. This was partly the fault of a 1980s school curriculum which insisted on several years spent in the company of Jude the not quite obscure enough. I disliked Hardy’s fatalism, found ‘done because we were too menny’ hilarious and especially didn’t buy the idea of landscape as character. But traipsing round the heart of Hardy’s Wessex I found something of what he meant when he wrote that his was a ‘partly real, partly dream country’ — somewhere in the shadow of the imagination. I was struck by how often I came across votives, notes and relics left for the recently departed at spots associated with the sacred: in yew trees that marked the boundary of the henge around the ruined church at Knowlton, a flash of the yellow flower goldenrod wrapped in some damp tissue paper in the crevice of a stone barrow, at another ruined church on Portland and in trees at St Augustine’s Well near the earthworks that mark the location of the abbey at Cerne Abbas, close to the giant’s monstrous priapism. We’re less inclined to tick C. of E. in a box on a census form, but like the nineteenth century rebels, people continue to find meaning in the land.

I don’t like the idea that books write themselves, that once the scene is set, the writer withdraws: there’s always agency, there’s always responsibility. Peter, my endlessly encouraging and patient editor, urged me to write about what interested me, but I find it hard to shake the notion that the book formed itself, slowly and sometimes painfully, out of Dorset, its landscape, rebellions, music, literature and people. I hope I’ve done it some justice, but immersing myself in Dorset’s specificity and variety was its own reward. Writing and researching wasn’t always pleasant: I fretted too much, got lost many times, was soaked to the skin on occasion, was shouted at by strangers twice and had a telling-off from a senior clergyman, but even these small misadventures enriched the experience. I’ve shelved the Dorset books and stopped the furious walking and note-taking, but find I miss the county’s constant company.

*

Jon Woolcott works for the publisher Little Toller Books. ‘Real Dorset’ will be published by Seren Books in 2023. Follow Jon on Instagram: @dorsetjonw.